If the Academic Revolution hadn’t elevated film history from the dustbin of trivia to a legitimate field of study, we might know a lot less about Chris Marker—not that we know everything now. The man chose his pseudonym because he thought it hard to mispronounce (though some conjecture he was a fan of Magic Markers) and refused press because he said ‘my films are enough for them.’ He evaded interviews, despite making complex film essays audiences would read about had they a chance, and asked not to be photographed despite having a central obsession with photography. Marker’s work assisted in the development of so many filmmakers and advanced the form, but if not for the constant pimping done on college campuses everywhere, and if not for habitual re-watching of La Jetée, this prolific film maker could have been forgotten. As he conjectures in Sans Soleil, at some point a photograph could replace a memory, and at a loss for record we’re left with lore.

Concerned with time and also seeming to operate outside of it, Marker had a fondness for slogans and animals. His own cat, Guillame-en-Égypt, even appeared in later films as an animated orange tomcat, and when asked for pictures of himself Marker would often provide snapshots of Guillame. These little quirks seem to lead down a rabbit hole of truthy nicknames and accidental avatars. He so loved film collectives he invented names and identities for his credits so no one would know he’d done all the work himself: thus, Marker was many men. In Agnes Varda’s biographical documentary The Beaches of Agnès, Marker appears as the cartoon Guillame. It seemed like something he’d done a lot—as if he and the cat were playfully interchangeable and his hunt for yellow cat graffiti in Case of the Grinning Cat was also (maybe) a quest for self-exploration. This may be overstatement, but whatever his reasons he obviously found comfort and animals in the same places. When the Onassis Foundation funded his TV documentary on Greece he named it for the animal on their currency: the Owl. And in The Owl’s Legacy, the owls (and the Greeks) are snuggly.

Marker imagined the future held an electronic language that everyone would use to “list things that quicken the heart.” (Doesn’t that sound like Twitter or Pinterest?) One of his last films, Leila Attacks, was a one minute epic of tiny rodent aggression. This came after a career in which he’d tucked animals into most empty spaces. He says in Case of the Grinning Cat ‘The angel is to the man what the hole is to the cat.’ How isn’t Chris Marker the progenitor of CuteOverload?

Marker has more recognized works and lesser-known works, like any filmmaker, but he’s one of terribly few art film directors who directly inspired a blockbuster. Twelve Monkeys appears to be the most insidious demonstration of the power of film school American Studios hath wrought. The story goes that Universal executives presented screenwriting couple David and Janet Peoples with Marker’s 1962 sci-fi short La Jetée in hopes they’d adapt it to a big, imaginative, Christmastime release: something splashy with explosions, a crazy futurescape and a schmaltzy romance. The Peoples hedged, saying La Jetée “what could we improve?” but the executives seemed to understand a movie with more Bruce Willis and less philosophy could draw a greater crowd than an obscure photomontage about time and memory ever could. Yet those who loved La Jetée would be curious ticket buyers and those unfamiliar would be drawn in by various other shiny lures. Terry Gilliam was fresh off his success with the psychiatric fantasy The Fisher King when he directed Twelve Monkeys, and he conferred with Marker in pre-production. What Universal produced has become a film studies gateway drug.

Emiko Omori, a San Franciscan documentarian, worked with Marker and recently produced a film on his work and their friendship called To Chris Marker: An Unsent Letter. In it both Gilliam and the Peoples’ describe Marker as impressively cooperative and the only sticking point the screenwriters noted was Marker’s disapproval that the main female played by Madeline Stowe be a psychiatrist. The Peoples’ were apologetic but ultimately said, “everyone needs a job.” One supposes this is the difference between 1962 and 1995. Some futures are unforeseeable.

Marker was part of the Left Bank Film Movement in the era of the French New Wave and, like Truffaut, Godard, Rohmer, et al), contributed to Cahiers du cinéma. As a movement they didn’t ballyhoo a manifesto, nor did they fight and fraternize the way the pop-loving Cahier kids did. I remember them like vowels: Colpi, Marker, Resnais, Varda, Gatti and sometimes Demy. They contributed foundational works but each with a preoccupation. Alain Resnais, the man behind Last Year at Marienbad, shared in Marker’s fascination with memory but added to that a concern that time dilutes romance. Armand Gatti was in the French resistance and, of the group, likely saw the worst of the war; at least this is what we can glean from the traumas he depicted in POW drama Enclosure. Henri Colpi’s debut The Long Absence is based on a script by Left Bank novelist Marguerite Duras, and initiates a theme of family betrayal. Agnès Varda, “the grand dame of the Nouvelle Vague,” and wife to Jacques Demy, was known for “feminist issues,” a phrase I take as code for her almost-judgmental representations of unfaithful French husbands.

The Left Bank filmmakers felt responsible for international events, and were determined to accomplish something important by representing them. Their ingenuity with the genre inspired journalists to come up with new terms to describe them—these terms usually stunk so didn’t stick. Marker’s documentaries were occasionally called “new documentaries” in some foolish attempt to declare formal uniqueness, but he’s more accurately called a film essayist and best compared to icons of French composition like Enlightenment essayist Michel de Montaigne. Marker’s film-essays bordered the academic in their meticulousness but favored photomontage as a way to distinguish motion picture from photography as the media of record in time—it was one of ways he presented information plainly and still left room for interpretations to seep in between the frames. He embraced new media, playing with digital video in Sans Soleil and CD ROMs and websites with “Immemory” (made with Gatti’s help). He embraced the changing tides, and there were many.

La Jetée wasn’t Marker’s first film: his debut was a 16mm short about the Helsinki Olympics called Olympia 52 and thereafter he worked on a few films with Resnais, most notably Statues Also Die (1953). Separately he produced two almost agit-prop films about conditions he observed working as a correspondent (journalist) abroad: Sundays in Peking (1956) and Letters from Siberia (1957), for which he traveled with Gatti. Prior to filmmaking he participated in World War II—whether he was a fighter pilot or a desk jockey is a fact contested by fans and historians. On the subject of his similarly undetermined place of birth, critic David Thomson said Marker confirmed he’d been born in Mongolia but Thomson concluded Belleville, in France, was actually correct. Said Thomson: “–that does not spoil the spiritual truth of Ulan Bator.” Meanwhile, many sources list his place of birth as Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. In my imagination, future generations who have lost bits of the historical fabric might reconstruct Marker’s story and have a similarly difficult time rendering conclusions about La Jetée and 12 Monkeys—perhaps those films also have a literal and a spiritual truth. What came first: the chicken or the Easter egg?

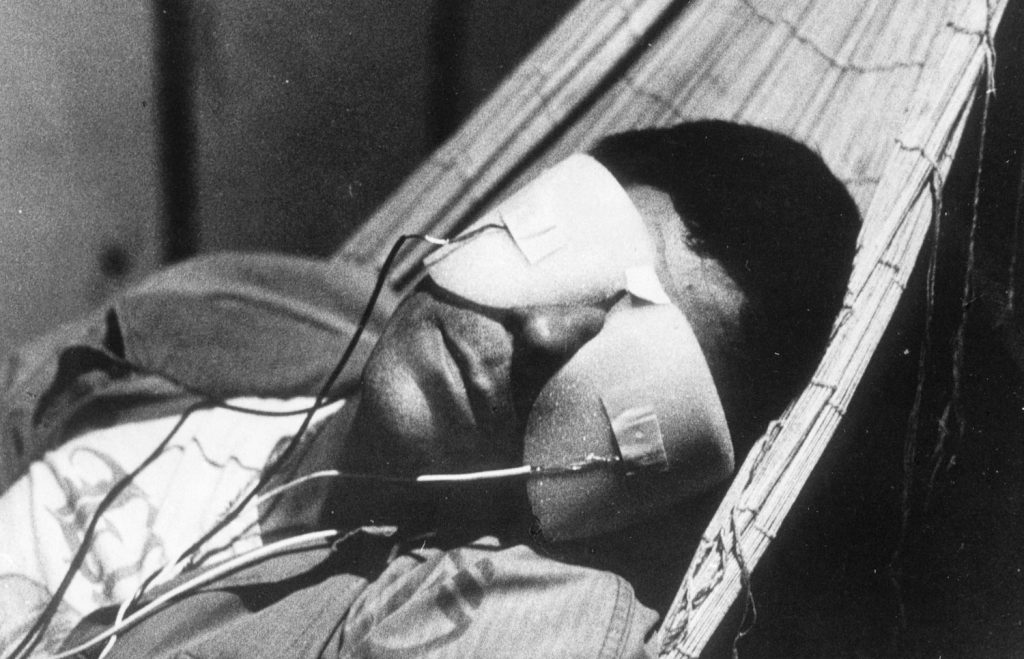

Marker contributed an essay to the Criterion disc for La Jetée and Sans Soleil and in it he revealed some of his celebrated moments were the result of small budgets. The famous moment of motion in La Jetée exists because he could only borrow a motion picture camera for one day. The realities of that production history—whether charming truths or charming tales—cast a strange light on photomontages, like Sans Soleil, that seem to interrogate the value and use of the photograph. As his actress/narrator reads his letter to a friend (and weren’t all Marker’s voice overs like letters in spirit?), the intimacy is unavoidable. Alexandra Stewart swaps places with Marker when she asks if a photo (or surrogate) could replace the memory—again, interchangeability. Like a secret, her question coaxes you to reconsider the fun you had on your last picturesque vacation. Do you remember your dead relatives first hand? Have you had good times that produced ugly photos? Do selfies dream? Marker has a loose answer to these anxieties: in La Jetée, the narrator tells us “Nothing sorts out memories from ordinary moments. Later on do they claim remembrance when they show their scars.”

Marker edited the script for Resnais’ famously short holocaust documentary Night and Fog (1955). Like La Jetee, Night and Fog juggles film and photomontage, justifying its 32 minute running time with the thesis that the horrors of genocide can’t be comprehended through images and looking longer cannot teach us more. (Claude Lanzmann, director of the nina-and-one-half-hour Holocaust documentary Shoah, disagrees.) Yet these images of horror, the narrator says, have a deceiving ability to make us “pretend it happened all at once, at a given time and place.” Pictures become a tool for memory, and wouldn’t the opportunistic memory prefer to use them for comfort?

By the mid-seventies Marker had published two collections of film essays called Commentaires (I and II) and organized an omnibus film about Vietnam to which most of the New Wave majors contributed—they even scored a contribution from documentary legend Jori Ivens. The film, Loin du Vietnam, was so successful at creating a cohesive group, Marker started a salon. In the interest of overcoming his disappointments with the New French Left, he made efforts to encourage industrial workers to make film collectives of their own. Marker dedicated himself to the salon (aka S.L.O.N.), relinquishing his personal works, though he often received co-director credits for SLON films. He’d return to personal work in 1974 with (of all things) a doc about friend Yves Mondant’s concert to benefit the Chilean refugees who fled the military overthrow of Salvador Allende. It’s no wonder Allende and Cuba factored so strongly in his 240-minute treatise on the flawed movement, A Grin Without a Cat. He could just as soon have called the film “Hope Without Proof.”

Marker’s A Grin Without a Cat is very associative in form. In it, he juxtaposes the Cuban revolution (a subject he also explored some in his 1961 doc ¡Cuba Sí!) with ample interviews from members of the Prague Spring, the Watergate Scandal and the politicians surrounding Allende. The film’s title in French means “The Air Is Essentially Red” suggesting the “Red” (socialist/communist) movement is hot air. Like the affectionate 2003 doc about photographer Denise Bellon (Remembrance of Things to Come) this film compares movements and battles to prove their commonalities and impotence—a war is a war is a war. Marker uses May 1968 as a line in the sand: it was a time when France saw widespread worker strikes and student protests, as well as the union between the French Socialists and the French Communists movements (aka The New Left). Despite the uplift before May 1968, the time that followed proved the socialist movements were sticking like snow to warm pavement, disappointing those hopeful for a mass communion in the collectively shared open air.

Marker doesn’t seek an ultimate or comprehensive representation because he found power in the subjectivity of truth. Narrating AK he quotes his subject Akira Kurosawa describing his approach to his Lear-inspired epic, Ran: “We shall try to see what we see, how we see it, from our eye level.” Perhaps this is why his film on fellow postwar field journalist Denise Bellon (which he directed with her daughter Yannick Bellon) organized the journalist’s work around the wars, because the war and the post war phase had provided him a sort of painful, guiding influence.

Focusing on Bellon’s photography from 1935-1955, Remembrances of Things to Come posits her photos imagined the war no one saw brewing. Marker identifies disturbing examples of “history repeating itself”—such as the parades of conspicuous wealth that preceded both wars—but somehow the events that hang as if on a clothesline between the poles of WWI and WWII resemble the arch of a career—inverted. Like Marker, Bellon reported from far corners of the world, the sort of journalism that shortened the distance between people nestled in their homes and cultures surviving in vulnerability abroad. Then, as the tolerance for such material dwindled, Bellon (like Marker) spent small phases capturing adorable animals or children.

Remembrance of Things To Come opens inside a gallery revival of Surrealist artwork. While Denise Bellon was a friends in the movement, this show paradoxically shows that after the movement had a career thumbing its nose at the establishment it’s now being celebrated by the museum industry it admonished. Maybe this is what success looks like, but it wasn’t visualized as part of anyone’s 25-year plan. Inevitably the future is full of things you have to re-contextualize using your memory. The first scene of La Jetée ends on the apocryphal truth: “Later, he knew he’d seen a man die.”

Marker passed away July 29, 2013, ninety-one years to the day he was born.