Editor’s note: We re-run this article from 2015 with new material as Fandor premieres I Always Said Yes: The Many Lives of Wakefield Poole [Note: This article involves explicit material NSFW or underage viewers.]

Jim Tushinski’s documentary I Always Said Yes: The Many Lives of Wakefield Poole pays tribute to a filmmaker who’s been inactive for decades, and is remembered by relatively few aficionados of vintage erotica. But for a few years, Poole was a significant cultural force at the center of Gay Liberation, even if his movies seldom any had overt political content. Of course, just making explicit gay movies that bothered to be imaginative and artistic at the time was quite political enough. His was a career it’s hard to imagine in any context but that of the “Me Decade,” when porn not only became legal, but for a while there looked like it was actually becoming culturally “respectable.” Poole was one of the most significant talents who were then taking it out of the grindhouse and pushing it toward the arthouse.

In the wide-open 1970s, when the Sexual Revolution hit full bloom, there was a brief phenomenon of “porno chic.” That was the label placed on the (rather short-lived) period when, thanks in large part to the breakthrough success of Deep Throat, it became OK for adventurous, respectable people (women too, not just the usual “raincoat crowd” of grindhouse-patronizing men) to attend pornographic movies. In public yet, at the theater, because VHS and cable wouldn’t begin to make porn a home-viewing affair until the next decade.

I’ll bet most couples who succumbed to the lure of “porno chic” once didn’t return for more. While seventies porn flicks generally sported a lot more not-strictly-sexual content (i.e., attempts at narrative, characterization, sometimes satirical or serious dramatic content) than they do today, even then most such films were cheap ’n’ sordid. They were frequently juvenile in humor, uninspired-to-amateurish in technique.

But there were exceptions, reflecting the belief among some at the time that a liberated sexual atmosphere would surely lead sooner or later to dissolution of all boundaries between “pornographic” and “mainstream” movies. Surely one day soon Hollywood marquee stars would routinely do graphic sex scenes, and famous porn performers like Marilyn Chambers and Harry Reems would appear in major-studio blockbusters! This proved a delusion that passed as quickly as a fever, even though some notable talents did get their starts in “raincoat crowd” movies—among them Francis Ford Coppola, whose first feature was the 1962 “nudie cutie” Tonight for Sure, and Bad Lieutenant’s Abel Ferrara, who debuted with a 1976 XXX film delicately titled 9 Lives of a Wet Pussy. Indeed, the sketchy semi-underground of softcore cinema had long laid under-sung but significant groundwork for independent American filmmaking in general.

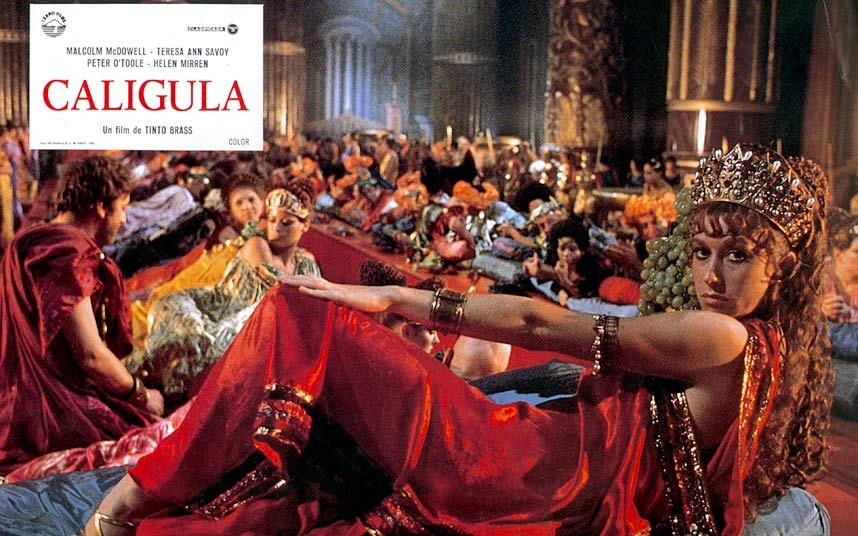

The imagined crossover between porn and mainstream movies never came to pass, unless you count Penthouse Magazine tycoon Bob Guccione’s eighteen-million-dollar 1979 Roman epic Caligula, in which A-list actors (Peter O’Toole, Malcolm McDowell, Helen Mirren) enacted the drama, while nameless extras performed in hardcore inserts. Though eventually a home-video and cult success, its struggles to find theaters that would play it (not to mention the countries that banned it whole) reinforced for many the notion that real, graphic sex would never have a place in “regular” commercial films.

Nonetheless, for a time, that belief and the “porno chic” vogue encouraged certain filmmakers to actually express some fairly interesting thematic and stylistic ideas in “XXX” films. Deep Throat director Gerard Damiano made 1974’s Memories Within Miss Aggie, a mournful adults-only drama inspired by (of all things) Edith Wharton’s Ethan Frome. San Francisco’s Mitchell Brothers made several stylish and ambitious hardcore features. So did several European makers, and ditto a few directors in the gay-porn world that served a wholly different market. (And a different business infrastructure, which was fortunate: Unlike heterosexual porn, gay porn cinema didn’t have its financial aspects largely controlled by profit-stealing mafioso types.)

Artistic notables in that latter department included the musclebound actor/producer/director Fred Halsted, whose 1972 feature debut, L.A. Plays Itself, ends in an LSD freakout of cinematic and orgiastic intensity; and Peter Berlin, another multi-hyphenate talent who made exactly two unique feature-length odes to himself, Nights in Black Leather and That Boy, then retired at age thirty-two. (I Always Said Yes director Tushinski also made a documentary about the latter, called That Man: Peter Berlin.) But for a while the biggest name behind the camera in gay porn was Wakefield Poole, a former ballet dancer, choreographer and stage director who amidst the heady Gay Lib atmosphere of the early 1970s decided to abandon his successful Broadway career to make erotic films.

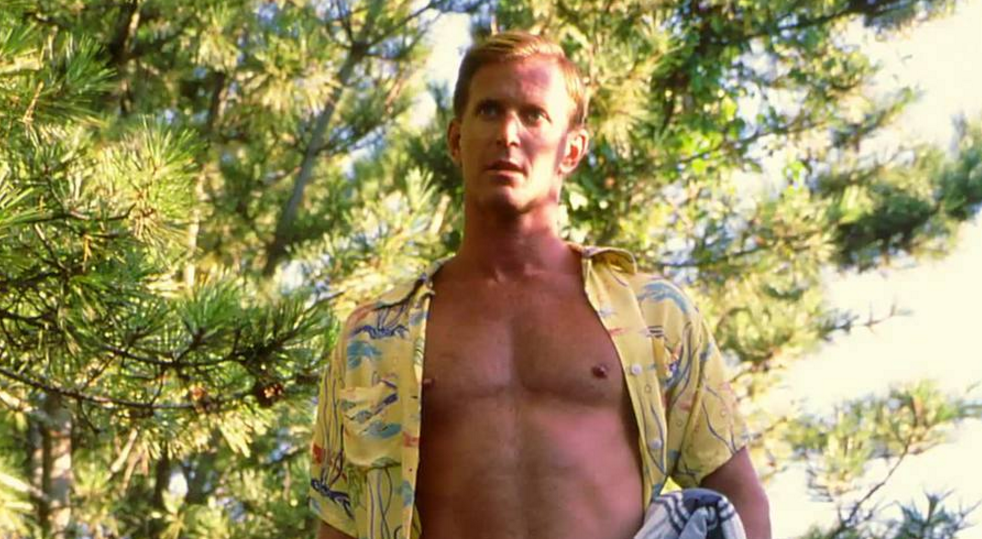

Boys in the Sand (1971) started life as a short Poole shot with his lover Peter Fisk and a couple friends, intending only to show it privately. But he was so pleased with the results he decided to film additional segments and assemble a commercial feature. Purportedly shot over three weekends on Fire Island on a budget of $8,000, it was an enormous success, making a celebrity of classically handsome blond actor/model Casey Donovan a.k.a. Calvin Culver. (Though like other talented actors such as Reems and Georgina Spelvin, he would find that porn notoriety basically squelched his hopes for a mainstream acting career.) Reacting against the “dirty” ambiance of the few gay sex films to date, Poole had made something very few of them (or heterosexual porn films, for that matter) would ever be: Boys was actually sweet, playfully romantic as well as explicitly sexy. As the director later stated, its performers weren’t just having sex: They were making love. It was the first XXX feature (gay or straight) to actually credit its makers and cast members onscreen, even if some created pseudonyms for the occasion.

While the episodic 16mm film of variably lyrical and humorous vignettes (sans dialogue, scored to classical, Muzakish, rock and sitar tracks) may look quaint now, at the time it seemed a refreshingly polished, artistic effort in a genre that had hitherto all too often been sleazy and poorly crafted. Favorably reviewed by numerous “straight” publications, it arrived several months before the heterosexual XXX phenomenon Deep Throat, helping to foster “porno chic” and impressing many as evidence that homosexuality was now “out of the closet” for keeps.

That success allowed Poole to think a little bigger: Bijou would be a dream-like piece unlike anything in sexually explicit cinema to date. Its hero is a construction worker (Bill Harrison) who appears like any other working stiff (ahem), save that when he pleasures himself in his dingy NYC apartment, the audience invariably gasps (as apparently did Poole’s filming crew) at the scale of an “endowment” best described as “alarming.” Earlier in the day, this nameless protagonist had accidentally come across a printed invitation to the unfamiliar titular venue, good only for that night. He traipses off, with no idea what kind of “entertainment” he’ll find there.

What he gets is a mysterious “club” with very restricted admission, in which he’s silently instructed to doff clothes and begin moving through a maze of diverse sexual experiences against arrestingly dark, minimalist settings. (Poole shot these scenes entirely in his own loft, using black-velvet backdrops to out anything but his stylized lighting.) At this point Bijou becomes a plotless but hypnotic exercise in screen surrealism: enigmatic, fantastical, and always highly sensual. While its main figure appears to be heterosexual in orientation (at least before his invitation-only adventure), he undergoes a baptism in same-sex lust that the film encourages viewers to guiltlessly share in the final close-up of his giddy, satiated post-“Bijou” face.

Indeed, Bijou was admired by some prominent mainstream critics, and publicly embraced by celebrities like Andy Warhol and Yves St. Laurent. It was another big hit that ran in theaters for months…although just a few theaters, as these were still the days of pornographic movies facing semi-random, regional prosecution on obscenity charges. (Poole and Fisk frequently hand-delivered their prints after flying to various city venues, in order to circumvent the strict laws regarding mailing of obscene materials.) After that, Poole was a bona fide auteur, at least to a certain sexually and culturally sophisticated audience. So why not “cross over” to more mainstream, even heterosexual cinema? Originally titled Wakefield Poole’s Bible!, his next, most ambitious and expensive project would be an erotic spin on several stories from the Old Testament: A book that, needless to say, has plenty of sex and violence tucked into its moralizing gist. First, there would be a lyrical depiction of the Creation story, with Adam and Eve as innocents finding one another against striking coastal scenery (shot in the Virgin Islands). The fable of David and Bathsheba (The Devil in Miss Jones’ Spelvin) would be played out in manically farcical, slapstick terms, while Delilah’s emasculating of Samson would take on a more poetical, slo-mo tenor. Finally, a brief vignette portrays the “immaculate conception” as a balletic pas de deux between the Virgin Mary and a sexy angel.

With only a single line of spoken dialogue, Bible! is a playful, visually imaginative episodic pantomime that Poole intended as “an adult Fantasia,” mostly scored to excerpts from classical pieces by the likes of Vivaldi and Prokofiev. Initially wavering on whether to make it a hardcore film or not, he decided on the latter. Yet despite a complete lack of explicit sex, simulated or otherwise (though there was some full-frontal nudity), it encountered a tidal wave of prudish resistance. As the director wrote later (in his autobiography Dirty Poole), “People have no sense of humor when it comes to religion.” Bible! was snubbed by distributors and independent theaters alike; despite positive response from the few journalists who’d seen it, most newspapers refused to allow advertising or reviews. This “total financial disaster” ate up most of Poole’s savings from his prior hits, though they continued to bring in money.So, he retreated to gay porn, while also venturing into other fields (like a San Francisco art gallery/clothing store called Hot Flash) and profiting from an early investment in longtime friend Michael Bennett’s longshot project turned record-breaking Broadway musical A Chorus Line. With the exception of 1977’s Take One, which mixed elements of Boys and Bijou, by all accounts his later films seemed less inspired. That was largely due to a cocaine addiction he would later be somewhat thankful for, because it made him incapable of participating in the urban gay sexual smorgasbord he’d hitherto been very active in during what would emerge as the most dangerous years of U.S. HIV contagion. But his films also had to cope with a by-now-crowded field of gay XXX films in which they inevitably seemed less special than before.

Though Poole persevered through this difficult period (even releasing Boys in the Sand II with the returning, subsequently short-lived Casey Donovan in 1984), the AIDS epidemic took an enormous emotional and creative toll. “It seemed as though death was using my address book to make his house calls,” he later wrote. Nearly all his peers and lovers died. Needing a job, Poole realized he was good at something that didn’t exactly make him “hirable,” and went into food services as a chef and corporate manager.

He’s stuck around long enough to see a revival of interest in his groundbreaking early features, including Bible!, which was basically a lost film for nearly four decades until its recent restoration for home-formats release. Among other treasures recently re-issued from his peak period are several shorts that suggest the breadth of his cultural interests: Andy is a strikingly edited and scored appreciation of a Warhol exhibit; A Gift (attributed to both Wakefield Poole and Ed Parente) provided a charming, abstract love poem from one close friend to his boyfriend; Vittorio is a brief animation made to accompany a gallery exhibit. Head Film was an experimental lark much influenced by the avant-garde and gay “camp” sensibilities of the era. In it, he makes a rare onscreen appearance alongside lover Fisk, who provides a naked demonstration of how to prepare veal a la Julia Child. One has no doubt that artistically, sexually and even gastronomically, they were living life to the fullest in an era when “If it feels good, do it” seemed as sound a life philosophy as any.