[Editor’s note: This week’s selection of Criterion-via-Hulu films centers on the theme of “Classic Books.”]

Along with George Orwell’s Animal Farm, William Golding’s Lord of the Flies is one of the most widely read social allegories of the twentieth century. The novel, a dystopian fable about a group of English schoolboys who end up on an uninhabited island as the result of a plane crash, was Golding’s first, and the best-known in his Nobel Prize winning career. When Ealing Studios decided the film, which would feature an all-child cast, no adult stars and a potentially large budget, wasn’t worth the risk, the rights to the book were sold to producer Sam Spiegel, who’d gambled and won on David Lean’s epic Bridge on the River Kwai, and Lawrence of Arabia. The task of directing the film fell to Peter Brook, and the film he would make was quite different than Lean’s colorful widescreen sagas of male heroism.

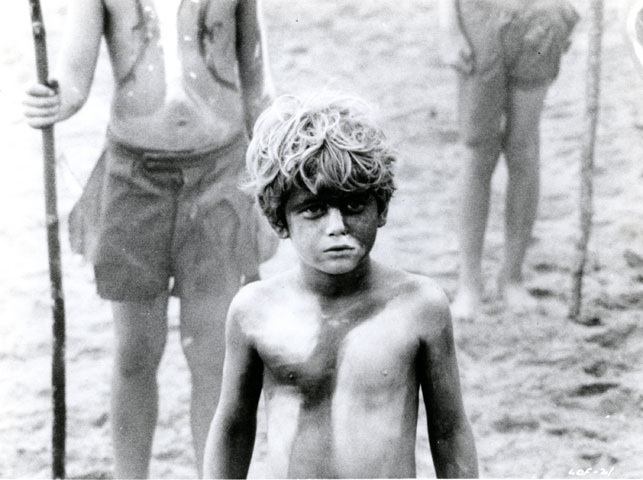

Peter Brook was a theater director known for his lavish, experimental productions. He had staged a controversial presentation of Richard Strauss’s opera Salome with sets by Salvador Dali. His Lord of the Flies seems at first out of step with that reputation. Working with a budget of less than one hundred thousand pounds, his crucial choices were to use children who were not actors, and to have his sets designed not by a surrealist painter, but by Mother Nature. Brook filmed in an almost documentary style on an island near Puerto Rico, and the black-and-white Academy ratio cinematography distinguishes the film. The influence of Antonin Artuad’s Theater of Cruelty can be seen in his stark, visceral staging of Golding’s bleak tale, particularly in the second part of the film, when this group of boys descends into wild violence. Following the film’s opening sequence, a brilliant montage of still photographs that establishes the story of these boys at school, their evacuation due to a war and the crash of their plane, we immediately arrive on the island. Brook spent a summer with the cast, shooting their improvisations of the book, largely without a script. The resulting sixty hours of footage was then edited over the course of a year. Among the early scenes in the film, the most remarkable are those with the young cast interacting with their natural surroundings. The film really comes to cinematic life, however, once the boy’s makeshift community begins to deteriorate.

Brook said his reason for “for translating Golding’s very complete masterpiece into another form in the first place was that, although the cinema lessens the magic, it introduces evidence.” The photographic evidence of these very real children succumbing to brutality is indeed presented, but Brook has conjured his own uniquely cinematic magic in the process. The scene in which the children, turned savage, hunt “the beast” by night, with deadly results, is particularly haunting, as the sparks from the fire dance chaotically around the dark frame, and the children’s feral screams fill the soundtrack. The delight of the film is in seeing the children begin to mimic their wild environment, and in hearing their cries and voices become indistinguishable from the screeches of the birds and other animals on the island. Often considered a faithful, straightforward adaptation of the novel, Peter Brook’s film is a dark visual representation of human tragedy.

Another take on human tragedy

Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles: A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented was first published in serial form in the British illustrated newspaper The Graphic in 1891. The novel was in many ways an affront to the sexual morality of late Victorian England, and crucial passages of the story were censored for the serialized version. The complete text was finally published in 1912. This tragic novel about a young peasant girl whose life is forever altered when her father discovers their family were once noble aristocrats, was allegedly given to director Roman Polanski by his wife Sharon Tate before her own life was tragically altered.

In 1978 Polanski’s career was going well, his previous movie, Chinatown, was successful, and highly regarded. His personal life was more turbulent. In 1977, he fled the U.S. for Europe as a result of his being charged with the sexual offenses against a girl in California. For whatever reason, Polanski chose that moment to film Thomas Hardy’s novel about a girl doomed in life largely as a result of a sexual assault. The film is largely faithful to the Hardy’s text. Natasha Kinski plays Tess as delicate, beautiful, if slightly aloof to the motives and desires of those around her, before becoming defiant and ultimately violent in the face of the hypocrisy of her fate. The film places Kinski against the lush backdrop of the French countryside, as photographed by Ghislain Cloquet and Geoffrey Unsworth. Cloquet, who’d worked with Robert Bresson on Au Hasard Balthazar, took over when Unsworth, who’d been Director of Photography on Kubrick’s 2001, A Space Odyssey, suffered a fatal heart attack during the third week of shooting. This collaboration resulted in a strikingly beautiful movie, particularly the exteriors that recall the realist paintings of Gustav Courbet. Hardy’s novel is rich with descriptions of the landscapes his characters inhabit, and one of the film’s triumphs is in bringing this pastoral beauty to life visually. Paralleling the tragedy of Tess’s struggles is the decay of her way of life by the encroaching industrial revolution, and as the film progresses we see more of the devilish machinery that will forever alter this rural society. The scene in which Leigh Lawson as Alec Stokes-d’Urberville pleas for Tess to return to his life against the cacophony of primitive farming machinery is a masterful example of this. Although not typical of Polanski’s work, Tess stands, along with Chinatown, as perhaps his greatest accomplishment as director.