“Coppola‘s films, more than those of any other American director of his generation, lend themselves to autobiographical scrutiny,” wrote Ronald Bergan in his 1997 book, Francis Ford Coppola: Close Up: The Making of His Movies. “In 1973, during the making of The Godfather Part II, he told journalists, ‘To some extent I have become Michael Corleone’ because, like the mafia boss, he was ‘a powerful man in charge of an entire production’ and married to a non-Italian as Corleone was. While Coppola was filming Apocalypse Now in the jungles of the Philippines, his wife Eleanor accused him of turning into Colonel Walter Kurtz, the megalomaniac officer whom the American army wished to ‘terminate with extreme prejudice.’ Coppola was already considered beyond the pale by the Hollywood establishment for having set up Zoetrope, his renegade independent studio in San Francisco. Apocalypse Now can be read on two levels—as an essay on the evil and madness of the Vietnam War, and as a study of the director’s own psychological breakdown.”

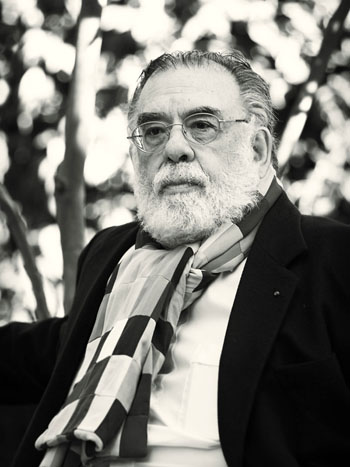

All that seems so long ago now. By all accounts, his 75th birthday finds him happy and, frankly, doing quite well as he runs Francis Ford Coppola Presents, which some Wikipedia editor describes as “a lifestyle brand… under which he markets goods from companies he owns or controls. It includes films and videos, resorts, cafes, a literary magazine and a winery.”

Following the unqualified triumphs of the two Godfathers (1972 and 1974), with the quiet masterpiece of 70s-era paranoia, The Conversation (1974) slipped in between them, then the far more traumatic triumph of Apocalypse Now, the financial disaster brought on by One from the Heart (1982), followed by modestly produced S.E. Hinton adaptations, The Outsiders and Rumble Fish, both from 1983, the still-debated Godfather III (1990) and the bombastic Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), Coppola’s last film before taking a ten-year break was a John Grisham movie, The Rainmaker (1997).

In 2009, Notebook editor Daniel Kasman wrote, “Tetro sees an artist coming out of his hibernation; still groggy and a little stiff in the joints, we can nonetheless recognize a welcome return of an American cinema of characters, of adults, and of maturity in no way pitched towards an ironic, alternative ‘independent’ crowd.”

In 2011, Twixt was greeted with mixed reviews. “He’s an elegant classical narrative filmmaker attempting to squeeze himself into an esoteric art-film box that doesn’t suit his sensibilities,” argued Chuck Bowen in Slant. But at the House Next Door, Fernando F. Croce found the 3D presentation “lovably bonkers… The most playful entry in the legendary filmmaker’s recent slew of idiosyncratic, personal projects, it examines the creative process as a knowing contemplation of Coppola’s exploitation Roger Corman days, its narrative a chunk of gothic wackiness that suggests Dementia 13 remade with the gaudy romanticism of Rumble Fish.”

In 2012, on the occasion of the release of a box set of five films on Blu-ray, Solvej Schou spoke with Coppola for EW and found him dreaming big again: “I have a secret investor that has infinite money. I learned what I learned from my three smaller films, and wanted to write a bigger film. I’ve been writing it. It’s so ambitious so I decided to go to L.A. and make a film out of a studio that has all the costume rentals, and where all the actors are. My story is set in New York. I have a first draft. I’m really ready for a casting phase. Movies are big in proportion to the period. It starts in the middle of the ‘20s, and there are sections in the ‘30s and the late ‘40s, and it goes until the late ‘60s.”

We hope that one’s still in the works.

Update: “The most powerful cautionary tale for the Age of Big Data comes from an unlikely place: Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, which turns 40 today.” Alexander Huls for the Atlantic:

The Conversation is a member of what you could call Big Brother Cinema, which spans the paranoia thrillers of the 1970s (The Parallax View, Blow Out, Three Days of the Condor) to modern action films (Sneakers, Enemy of the State, Mercury Rising, and Live Free or Die Hard). Most films of the genre preach to the converted, entertainingly boosting simplistic “surveillance = bad” rhetoric. The Conversation at first glance appears to do the same. But look closer and it’s more than that: a nuanced look at the unintended consequences of surveillance, the kind of movie that should be required viewing for every NSA and Google employee.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.