[Editor’s note: Keyframe begins a three-part series on Academy Awards past, which began earlier this week with a ‘What If’ Oscars for the silent film years that pre-date the inception of the annual awards ceremony and continued by rectifying mid-century snubs, highlighting films that, in retrospect, richly deserved awards. It ends today with a list of non-winning nominees from our past few decades who really deserved a trophy of their own. For a look at all the ‘alt’ awardees, peruse our e-book.]

It’s somewhat tidy to look back to the eighties as a cultural line in the sand. The decade had the strongest mainstream culture since the fifties, boasting a firm middle class, a clear top forty sound and a comical collection of arch fashion. Perhaps it’s just harder to align today’s mores with the disco/punk divided seventies or the culturally convicted sixties—those eras are more mystery than history, which is perhaps why Oscar’s best documentary nominees are obsessed with them. The narrative categories like to revisit the past, too but they often treat the subject with…flexibility. In 1985’s Oscar ceremony Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan hunted (limply) for answers, The Cotton Club expected to revise the golden age of jazz for televisions audiences and Amadeus asked less from text books and more from the nature of genius. Ah, the eighties—too far to heaven and too close to Watergate—the era couldn’t consistently provide traditional heroes instead focused on rebels. Don’t call it confusion—call it a full scale revamping of social expectations.

1985: Marlene

Best Documentary

Marlene Dietrich says early in the Oscar-nominated documentary about her that there are fifty-five books written about Marlene Dietrich and she hasn’t read any because she doesn’t give a damn about herself. The doc’s director, Maximilian Schell, was in the winter of his acting career when he made Marlene. Like Dietrich, Schell was a native German speaker and had a legacy of playing slippery characters—though he played the baddie more than she ever did. Schell’s (Marlene) was one of a few of docs he made about admirable women (My Sister Maria, about his actress sister, was the second biggest entry) and the doc was at once a breath of traditional Euro-charm and a strange feat of almost-revisionism. In glossy/gritty archival footage Marlene delivers evidence of the aged icon’s life in performance, while her voice over describes with epic aloofness her private life as the patron saint of DGAF. A star among stars, Dietrich is a hero to herself alone and that autonomy is memorable but begs you not to follow—the film helps you look up at her but she’s not a hero so much as a rebel.

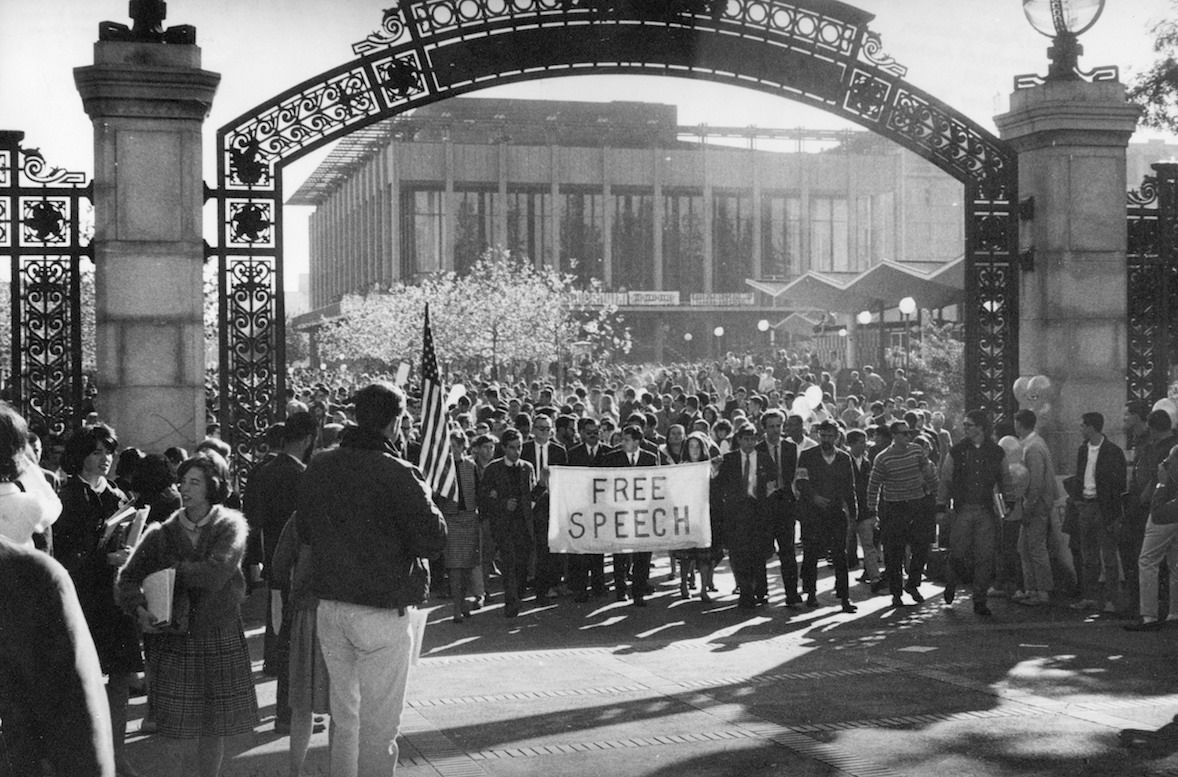

1991: Berkeley in the Sixties

Best Documentary

It can’t be a coincidence that six years later, Oscar noms were interested in revalidating legends: Young Guns II and Dances with Wolves pulled the western genre out of the dustbin and spit-shined it for public approval while Havana looked at a trenchant historical moment for answers about the day. Mark Kitchell’s doc nominee Berkeley in the Sixties was an expose about the messy, hard-to-record history in the capital of our American cultural revolution. Kitchell sifts through the rubble of this nation’s last zeitgeist only to find our triumph of public dissent provided less triumph than hard lessons about the utility of public assembly. Democracy is a leadership by the people and for the people; its existence is meant to fortify the hope-bringing autonomy of the individual and prove the little guy’s power to make change. What are we supposed to think when the model doesn’t work? Then again, are we really sure it didn’t?

1991: Metropolitan

Best Original Screenplay

Whit Stillman’s sophisticatedly naïve Metropolitan answers that previous conundrum with a punch line: in the upper echelons, no one can hear you peaceably assemble. Up for best screenplay against Green Card, Avalon and popular favorite (and winner) Ghost, we might look on Stillman’s reverse Cinderella story as its own “A Rose for Emily.” The nominees read like four Goliaths and one Whit—maybe the fact Stillman’s name is present at all proves the little guy can triumph.

1994: The Scent of Green Papaya

Best Foreign Language Film

Maybe history is written by the victors but the 1994 Oscar race was packed with stories that explained how the majority is silenced. Schindler’s List watched a vile profiteer be manipulated to save the lives of thousands and Philadelphia addressed the AIDS crisis and the marginalization of the afflicted through the story of an attorney suing for wrongful termination. Perhaps the most piquant and literal story of silence is Foreign Language film nominee The Scent of Green Papaya. The film watches a placid but poor child indoctrinated into a life of servantry. She cooks, she cleans, she’s denigrated by the children of the house and after her life of quiet diligence she is denied both money and sadness. Leave misery to those who can afford it.

1994: Black Rider

Best Narrative Short Subject

The same year Schindler’s List rocked the nomination, short subject Black Rider dangerously critiqued Germany’s “denazification.” From WWII on, cinema used The Nazi as its own go-to baddy and the German nation made great efforts to fix (see: Reconstruction), repay (see: Reparations) and/or forget (see: Heimatfilm) their part in the history of human atrocity (see: Third Reich). As part of German Reparations and a broader goal to demonstrate goodwill and escape financial devastation, Germany opened its borders to immigrants. Black Rider’s sly title doesn’t declare the nationhood of the rider/protagonist—that would be limiting, and anyway the bus riding old biddy spewing racial epithets isn’t giving him the benefit of a cultural heritage. Her heritage, by the way, is resplendently Master Race, and Reparations are just a bump in their otherwise eternal legacy of triumph. Is that terrifying? Black Rider thinks it’s hilarious.

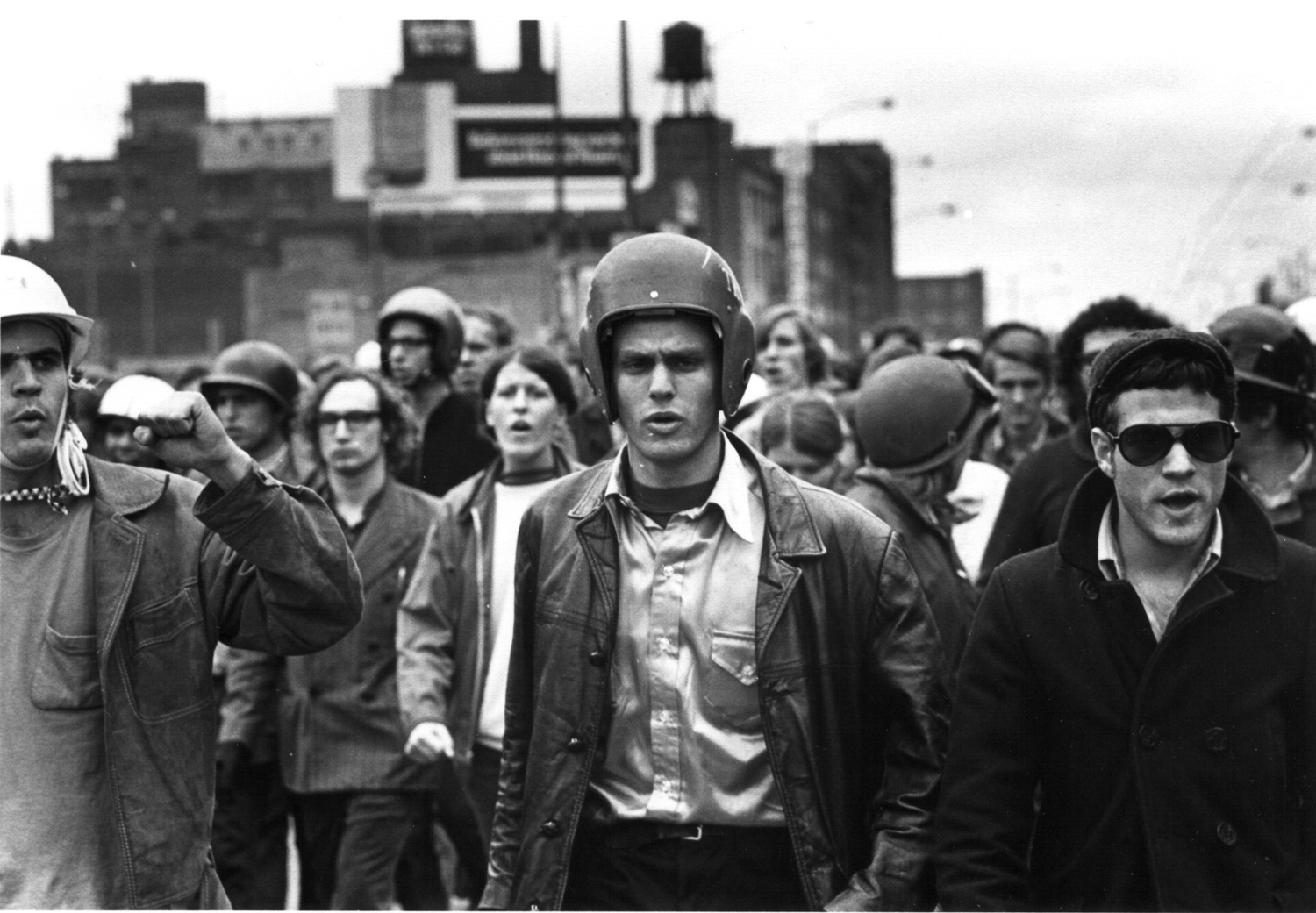

2004: The Weather Underground

Best Documentary

Sam Green refuses to let the history of American resistance lie quietly, and in his 2002 documentary The Weather Underground, he tracks the houseboat loving radicals who aimed to overthrow the U.S. government. In retrospect, 2004 nominees highlight a lot of magic in the water: Mystic River traced trauma through ripples upstream while Pirates of the Caribbean (how did that get on the list?!) portrayed pirates as wobbly, rogue strategists parallel to Jobs and Wozniak. I mean, really, how did we get where we are? While Errol Morris’ The Fog of War tracked the victor’s narrative about Vietnam, Green revealed American radicals were ambitious, ruthless risk takers—and forgetting that history is akin to pretending our nation is invulnerable.

2011: Dogtooth

Best Foreign Film

As Greece was teetering towards bankruptcy, the “Greek Weird Wave” (so-called by The Guardian’s Steve Rose) was hitting the states and Dogtooth, the most vital, perverse, multivalent metaphor for perspective led the charge. 2011 was the year Black Swan pit feminine aberrance against a King with a stutter (King’s Speech). Meanwhile, in the competition for Best Foreign Film, each entry was concerned with seeing ways outside their limited scopes. Javier Bardem hunted for a way out of poverty in Biutiful and Trine Dryholm cried for peace among warring families in In a Better World. Turmoil is evergreen and while the characters in Dogtooth have organized their world in avoidance of outside conflict, living in a bubble can’t provide safety. The magic of Dogtooth (which lost to In a Better World) is that its primary contrivance (a family raised inside a compound) is based on an ideal that can’t produce healthy fruit; you have to break the bubble to see outside it.

2013: The Invisible War

Best Documentary

Few film-based activist campaigns are as successful as the one begun by Invisible War filmmaker Kirby Dick. About the crisis of unprosecuted rape cases in the military, Invisible War promised to crack open a legacy of cruelty swept under the rug by the military’s justice system. The year this film was up for best documentary Lincoln, Argo and Hitchcock were having their ways with history; Invisible War called for a full-scale review of the military record and a redress of the grievances made by a growing number of women who’d been silenced by their authorities in the armed forces. Under threat of reprisals, endangerment, and terrors from within, the women who came forward changed the dominant narrative, defied their authorities and, by changing the landscape for future women in the forces, transformed themselves from rebels into heroes.