William S. Burroughs, at his centenary, remains an indelible presence. His writings, ideas, and influence are everywhere still, and it is as though the man himself were hovering right alongside them. So original a public persona, as vivid as ever some two decades after his death, is hard to shake.

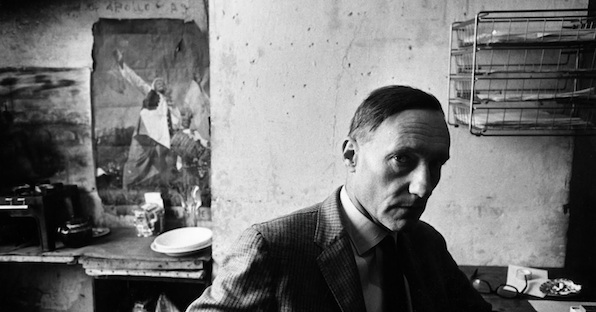

Few mugs are as iconic. The long poker face, imposing, rarely smiling (if not quite unfriendly), comes across as self-possessed as a cat’s. When there is a smile, it’s a little surprising: a delicate and playful thing, twitchy (never toothy), suggesting the giddy ambivalence of the solitary boy before a welcoming audience. And there’s the voice, prophetic and profane, a high nasal twang issuing from the top of the throat, determined yet reedy, before resolving itself into a contented grumble of half-chewed words.

But if we look closely again, the face, even the voice, begins to dissolve—not into the void but into multitudes. There’s Burroughs the literary outlaw; Burroughs the seasoned performer; Burroughs the suave public intellectual; Burroughs the merciless satirist; Burroughs the shy and reticent loner; Burroughs the gregarious host; Burroughs the serious cat lover; Burroughs the hopped-up, gun-toting coot—the writer, the addict, the mentor, the philosopher, the romantic, the humorist, the painter, the filmmaker, the conspirator, the collaborator, the inspiration to generations of outsider artists and high-profile rock-and-roll rebels. . . . The artist whose work sets out to erase the false line between reality and dreams comes to embody his own defiance of either/or thinking. He is quintessentially a both/and figure—at once so recognizable we think we know him, and so formidable he seems forever out of our ken, an enigma and an ally forever.

Plumbing the depths of William Seward Burroughs is a joyful and even revelatory occupation. An artist and intellect very much interested in exploring space—outer and inner—he left us much to fathom. Several documentaries provide an excellent starting point, variously tackling key periods and relationships in his adventurous, often reckless, indeed surprisingly long and uncompromising life.

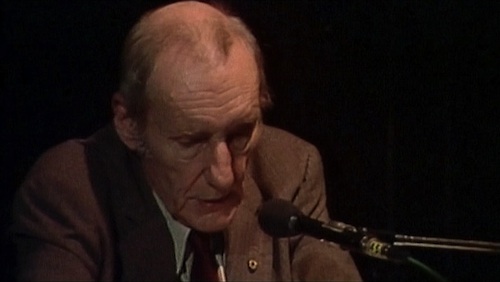

Klaus Maeck’s William S. Burroughs: Commissioner of Sewers (1991) is a charmingly constructed hour-long profile, featuring a wide-ranging interview conducted by German writer and publicist Jürgen Ploog. Hunched at a coffee table in the corner of a nondescript room, the two men ruminate on everything from reincarnation to the future of the human species. Asked at one point about the domain of the writer, Burroughs draws attention to a fundamental feature.

“One very important aspect of art,” says Burroughs, “is that it makes people aware of what they know and don’t know that they know. This applies to all creative thinking. For example, people on the seacoast in the Middle Ages, they knew the earth was round. They believed it was flat because the Church says so. . . . Cezanne showed what objects look like seen from a certain angle, in a certain light, and literally people thought he’d just thrown paint on canvas. And they attacked his canvases with umbrellas when they were first exhibited. Well now, no child would have any difficulty in seeing a Cezanne. Once the breakthrough is made, there’s a permanent expansion of awareness. But there’s always a reaction of outrage at the first breakthrough.”

Ploog’s interesting but subdued interview comes intercut with footage of Burroughs delivering public readings to boisterously appreciative audiences. These latter scenes blend with other archival materials, including fiery planes of color from the author-painter’s own canvases. There are pages and text from the cut-up novels, as well as black-and-white scenes drawn from his film work with filmmaker Antony Balch, including Towers Open Fire (1963), and The Cut-Ups (1966), made with Brion Gysin. We see and hear Burroughs reading from his essay “When Did I Stop Wanting to Be President?” (written for Harper’s magazine in 1975), a key line from which provides Maeck with the film’s title. We also hear excerpts from his well-loved “A Thanksgiving Prayer” (1986), dedicated to John Dillinger “in hope he is still alive.”

Burroughs the uncompromising artist, the serious and dignified intellectual, and the wry and bawdy performer achieve a productive, perceptive balance in Commissioner of Sewers, each persona casting light on the other.

But the perspectives of Burroughs’ own circle of colleagues and friends, as well as other close observers, add considerably to our appreciation of this complexity, and indeed multiply it further. In Words of Advice: William S. Burroughs on the Road (2007), filmmakers Lars Movin and Steen Møller Rasmussen get wonderfully thoughtful, candid interviews from the likes of Burrough’s longtime companion and editor James Grauerholz, Beat scholar and friend Regina Weinreich, poet and close friend John Giorno (regular opener for Burroughs at readings from the mid-1970s on), Sonic Youth’s Lee Renaldo, music producer Hal Willner (who produced Burroughs’ 1990 album, Dead City Radio) and many others.

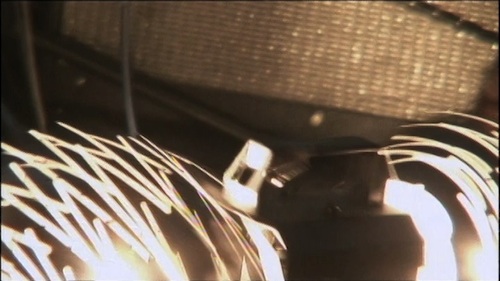

Particular insight into the Tangiers era of the 1950s, and especially the role played by Brion Gysin in the ideas and work of William Burroughs, comes in Canadian documentary filmmaker Nik Sheehan’s exhilarating Flicker, an exploration of Gysin and his dream machine—the whirling translucent cylinder that becomes a visual trope in almost any film portrait of Burroughs. (The device purportedly engages the brain’s alpha waves to induce a hallucinatory dream state.) “Created from systems of science, art, and magic, the dream machine is a kind of portal into the time/space continuum,” explains the filmmaker, who bases his exploration on Chapel of Extreme Experience: A Short History of Flicker by author John Geiger. Employing engineers to build a dream machine to the precise specifications, Sheehan then takes it with him to various initiates who can unlock its mysterious history and properties.

The brilliantly idiosyncratic Gysin—who died in Paris, poor and largely unknown, in 1986—met “his soul mate” William S. Burroughs in 1954 in Tangiers. Their formal collaborations on Minutes to Go, The Exterminator, and The Third Mind was, we learn, just the tip of the iceberg in a partnership that went beyond art into social subversion and realms of the occult. “Passing themselves off as an artistic avant-garde movement was a cover to quite an extent,” asserts Terry Wilson, a writer and close friend of both men, “a cover for their esoteric activities.”

In a world riveted by mass media, the individual awareness opened up by the dream machine represented, in the terms that marked a major focus of Burroughs’ fiction and concerns, “the ultimate way to defeat Control.”

The many featured interviewees here include some candid and intriguing insights from close friends and artists much influenced by the formidable pair, including Kenneth Anger, Marianne Faithfull, John Giorno, Genesis P-Orridge, Iggy Pop, Lee Renaldo, DJ Spooky and Nick Zinner.

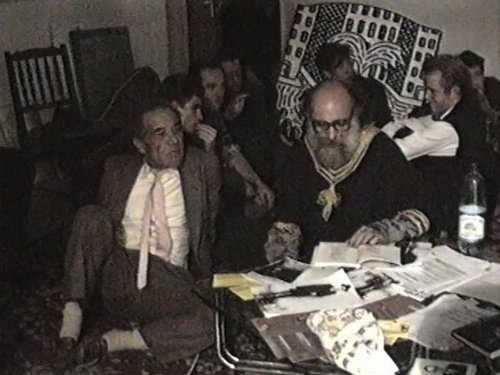

Destroy All Rational Thought (2006) offers further perspective on the unique and fertile partnership between Burroughs and Gysin. Also known as Celebrating William Burroughs and Brion Gysin in Ireland, this short film by Joe Ambrose, Frank Rynne and Terry Wilson documents the trio’s Here to Go Show in Dublin in 1992, a festive commemoration that drew an international set of friends and admirers. It featured a joint exhibition of Burroughs and Gysin’s paintings, as well as readings, impromptu parties, and musical performances—including by special guest performers the Master Musicians of Joujouka, from the Rif Mountains of Morocco, and their leader, Mohamed Hamri, a storied character and a friend of Jean Genet, Gysin and Burroughs. (As we learn in Flicker, it was Gysin who introduced Burroughs, along with Paul Bowles and Brian Jones, to the mountain village and the Master Musicians, initiates in a pre-Islamic brotherhood of witchcraft-practicing shamans.)

Interviews with Hamri and others, as well as archival footage (including some by the late filmmaker and erstwhile collaborator Antony Balch, flesh out scenes of poetry readings, rowdy reverie, and ecstatic jam sessions.

Burroughs, who was unable to attend but generously supported the venture, recorded a video from his home in Lawrence, Kansas, which played at the opening of the exhibition. It begins with Burroughs, subdued and pensive, seated near the creek in his backyard, introducing Gysin as “the only man I have ever respected.” He adds, “He was completely enigmatic because he was completely himself, which I think accounts for the fact that he was never successful as an artist—because he was himself, and most people are not. They saw him as a threat. And rightly so, I suppose.”

“As for painting,” continues Burroughs, “everything I know about painting I learned from him. And it’s an understatement to say my painting is derivative.”

Some of the more vulnerable sides of Burroughs onscreen and off come across in Yony Leyser’s William S. Burroughs: A Man Within (2010). Narrated by Peter Weller, this exceptional portrait also delves into Burroughs’ lifelong fascination with guns and other weapons (with some rarely seen footage of Bill at home on the firing range); his relation to the Punk movement of the 1970s (which he seemed to have predicted in his writing, including in Naked Lunch) and it also explores the nature and reach of his addiction to opiates.

But the greatest revelations are in the area of his private life, especially the complexity of his own sexual identity and capacity for intimacy. Genesis P-Orridge discusses the tragic self-destruction of Burroughs’ only son, William Jr., in a fatal attempt to seek the love and approval of his father. There is passing discussion too of Burroughs’ long and unrequited passion for Allen Ginsberg, and some touchingly delicate onscreen moments between the two friends. (More on Burroughs obsession and relationship with Ginsberg can be found in Alan Govenar’s The Beat Hotel, 2012, which faithfully explores that fertile period of communal living among Beat artists in late 1950s and 1960s Paris.) Still more revealing, however, is the unexpected picture we get here of Burroughs as a deeply passionate and troubled youth who seemed to fall easily and wildly in love, with extreme results (going so far as to cut off one of his fingers in one case).

As his former lover, the much younger Marcus Ewert, suggests, Burroughs’ deep affection for his six cats “was a safe place for his love to flow,” and reveals a man whose capacity for love was chastened and strictly channeled by the hard edge of his experience. In a dark and poignant irony, one boyhood infatuation during his time in New Mexico got the young Burroughs expelled from his school. This was the Los Alamos Ranch School, site of what would later become the Manhattan Project, the birthplace of the atomic bomb that would figure so aptly in Burroughs’ later visions of a mad and brutal world order.

Burroughs died of a heart attack in 1997 at the age of eighty-three. His writing is still voraciously read and digested, but his extensive work in other areas remains less well known. That may be changing, however, as access to his wider work becomes easier. Burroughs’ brilliant film work with Antony Balch and Gysin, for instance, is now just a click away on YouTube. And the above documentaries certainly help to spur wider interest in Burroughs the thinker, the covert activist and the multi-disciplinary as well as highly collaborative artist.

As for the man himself, Burroughs believed in the possibility of life after death. Indeed, he called it “the only goal worth striving for.” Wherever else he may be, as his longtime companion and editor James Grauerholz puts it in Words of Advice, “his immortality is in his readers.”

Or, as Burroughs and Gysin had it, more clinically and characteristically, in their Third Mind: “All dead poets and writers can be reincarnate in different hosts.”