[Editor’s note: Fandor is focusing on documentary films making a transformative social impact this month.]

A tree fell in the forest. No one was there to hear it. But I think by now we can all agree it definitely made a sound. Maybe there was a tape recorder on hand. And maybe there was also a finger to press Record—because somehow, the twentieth century’s most crucial environmental activist, David Brower, pumped that sound directly into politicians’ eardrums till they screamed uncle. After a towering career that can be credited with saving the Grand Canyon, preserving Point Reyes and rescuing too many other landscape hot spots to be named while putting the n back in dam, the cantankerous hero of trees, rivers, salmon and humans fell to earth himself, dying in 2000 in Berkeley at age eighty-eight.

Among the many who heard that sound was San Francisco filmmaker Kelly Duane. Scoring her documentary Monumental: David Brower’s Fight for Wild America with plaintive indie rock—nouveau Americana that feels so Pacific Coast you expect it to swim upstream to spawn—Duane has made a movie that is both elegiac and feral, a tribute to Brower the environmental activist working the system like it’s an extreme sport. Brower bitterly complained that so many of America’s environmental lobbyists are suits who never set foot on a mountain. Brower set foot (actually, initiated ascents) on many mountains—one so unexpected it helped the Allies in WWII (Brower’s 10th Mountain Division forged its way to key spots in 1942 Italy). His uncompromising footprints are all over the “Geography of Hope,” Wallace Stegner’s poetic designation of untamed wilderness, named in an essay about how the wild inspires, even if it’s only visited by the mind. Brower delivered that romantic mindscape to the people who could save it, bringing art—Ansel Adams’s and Eliot Porter’s photography, Stegner’s prose and his own films—to bear on the issue. In fact, Stegner credits Brower’s agitation with the genesis of the much-quoted “Wilderness Letter.”

Brower’s artistic legacy is what’s left of the unspoiled West itself, and he had the foresight to capture that West on film in case it wasn’t quite won his way. Filmmaker, surfer and rock-climber Duane got access to a massive collection of Brower’s 16mm forays by promising the University of California at Berkeley library where it was stored that she would catalog it. She’s more than made good on the promise with her re-presentation of those reels—a concentrated dose of Brower’s perspective on the woods, not so much diluted as augmented by talking heads who genuflect or haggle over Brower’s legacy. Duane uses the footage in a way Brower might have approved, as recruiting material—an introductory lesson in wilderness appreciation, set to a soundtrack (the Beachwood Sparks, Fruit Bats, the American Analogue Set, Hayden, American Music Club, Kingsbury Manx) whose variations on folkie free spirit and wistful “indie” notes pay tribute to roots without feeling dated by association.

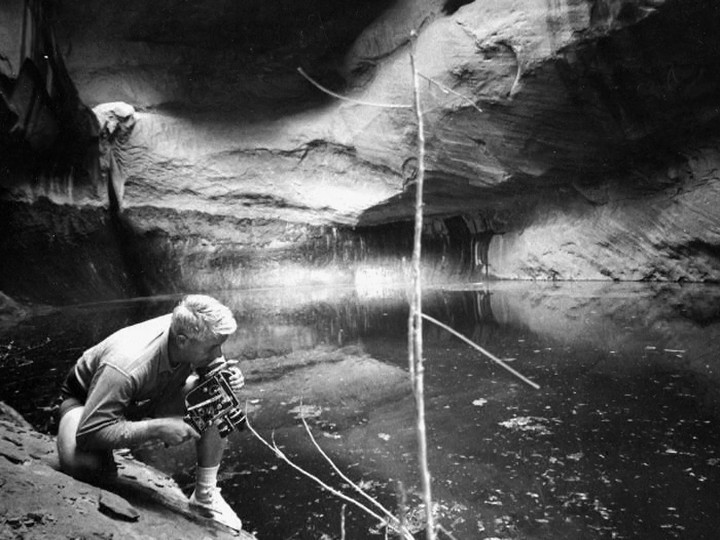

Bliss forms in the confines of a genre that rarely lets air in. Edits take their time, letting whole nature scenes play out over the course of a song, as opposed to leaving those scenes in manicured garden formation. Rushing rivers, half-century-old mountain climbs (in crepe-soled shoes!), quaintly rough roads into what’s now a Disneyfied Yosemite, and the cave art of Glen Canyon (now a gas-filled power-boat puddle) don’t evaporate the way contemporary, clear-eyed 35mm “nature photography” can—they stick.

The Glen Canyon images clearly burned a hole in Brower’s retina. He collected them after he’d already allowed for an onerous compromise with the federal government: letting the canyon be flooded and dammed in order to save Dinosaur National Monument from the same fate. From that moment on, Brower would help the environmental movement abandon “compromise” as its primary M.O. Strangely, the film ends where many of us see Brower’s true career as visionary beginning: when he was ousted from a Sierra Club then lending its support to the Diablo Canyon nuke plant and founded Friends of the Earth. But what it captures is the way Brower actually saw. He was most definitely a seer: his bold-stroke campaign to save the Grand Canyon—a full-page New York Times ad asked, “Should we also flood the Sistine Chapel, so tourists can get nearer to the ceiling?”—could still be pondered today with boaters who love dams and the bikini-bursting water-skiers they bring. It’s a testament to Brower’s monumental status, and evidence of Duane’s skill displaying it, that so many of this film’s talking heads are still scratching theirs today.

This article appeared originally in the San Francisco Bay Guardian.