Skilled in both cultural criticism and formal analysis, film critic J. Hoberman pivots easily between blockbusters, B movies, cult curios and the avant-garde in his writing. His new book, cleverly titled Film after Film, is split between reviews of salient films made during the George W. Bush administration and essays on film’s second life as a digital medium. There’s been no shortage of ontological musings over the last 20 years, but they’re often couched in reactionary terms (prompted by Avatar, say, or the end of Kodak film). Accordingly, it’s a pleasure to read Hoberman synthesize so many different strands of post-photographic cinema in reviving André Bazin’s ever-evocative question, What is Cinema? While Hoberman’s politically oriented books have a conspiratorial tinge akin to Greil Marcus’s music writing, here he plays the cool diagnostician. Ernie Gehr’s Cotton Candy is on the same footing with The Matrix, both equally symptomatic (and richly suggestive) of film’s digital turn.

The transition has of course meant very different things for Hollywood directors, indie hopefuls and experimental artists. Even within the avant-garde, there’s been a tremendous diversity of reactions and provocations. Avant-garde filmmakers were among the first to experiment with video and early DV technology in the 1980s and 1990s; others continue to work on 16mm and 35mm against the tide of technology. Tacita Dean’s recent Artforum dispatch about celluloid’s bleak future begins by implicitly recognizing that artist-filmmakers have long depended on the industrial infrastructure for cameras, film stocks and processing labs: “The survival of film—photochemical, analog film—depends on it being understood as a medium within the industry that historically and commercially used it the most: the cinema industry.”

With ‘Light Work Mood Disorder,’ Reeves reworked crumbling institutional films by hand before setting the material back to chance in the double projection. ‘Light Work I’s’ high-definition glaze, along with Anthony Burr’s droning score, gives tangible form to the distance Hoberman attributes to ‘Cotton Candy’s’ documentation of the pre-cinema toys in San Francisco’s Musée Mechanique: ‘the DV of the future tenderly [regarding] the more human machine of the past.’

Putting aside the question of what exactly this “cinema industry” is, Dean does nonetheless capture the paradoxical position of an artist committed to last century’s technology. Hoberman points to an elegiac style that developed ten years ago with films like Jean-Luc Godard’s In Praise of Love (2001), Bill Morrison’s Decasia (2002) and Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn (2003) (he might also have included composer William Basinski’s 2002-2004 series of recordings, The Disintegration Loops). Hoberman brackets all these films as iterations what filmmaker Lynne Sachs has called the “fetishism of decay,” before vaulting forward in time to discuss how filmmakers as varied as Guy Maddin, Ken Jacobs and Trey Parker have revived outmoded photographic technology in their films.

Of the American avant-garde’s response to the post-photographic moment, Hoberman focuses on Michael Snow, Gehr and Jacobs. All three have long been important for Hoberman, and all three share a pronounced analytic impulse. “[They] were all at one point in the late 1960s and early ’70s considered to be part of the ‘structural’ tendency in avant-garde filmmaking, heavily invested in the specific properties of the film medium,” he writes. “In switching to digital technology, they had demonstrated a comparable concern with the nature of this new medium.” Indeed, one could argue that insofar as the new medium renews the structuralist imperative, these artists were specially disposed to the digital (Michael Sicinski expands on related ideas with great interest in the first installment of his new column, “The Big Ones”). But what of the filmmakers for whom expression is unthinkable apart from celluloid’s intense concentration of time and light?

It would be interesting to know what Hoberman made of something like Light Work I, a digital hybrid made by an avowed believer in film as film. Jennifer Reeves’s 16mm work is certainly eclectic, ranging between cracked hand-painted movies (The Girl’s Nervy), lyrical shorts (Trains Are for Dreaming), feature-length narratives (The Time We Killed) and multi-projector performance pieces (When I Was Blue, Light Work Mood Disorder).

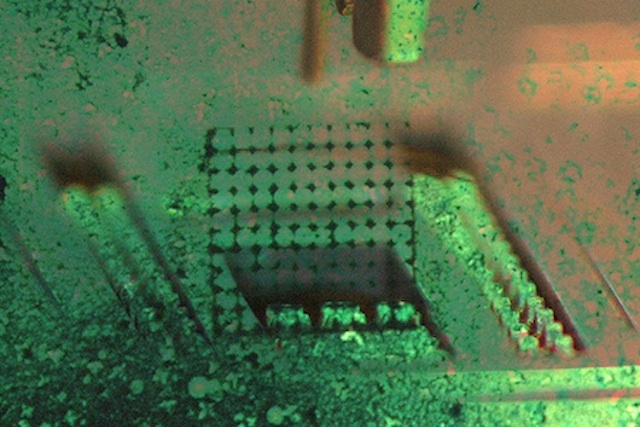

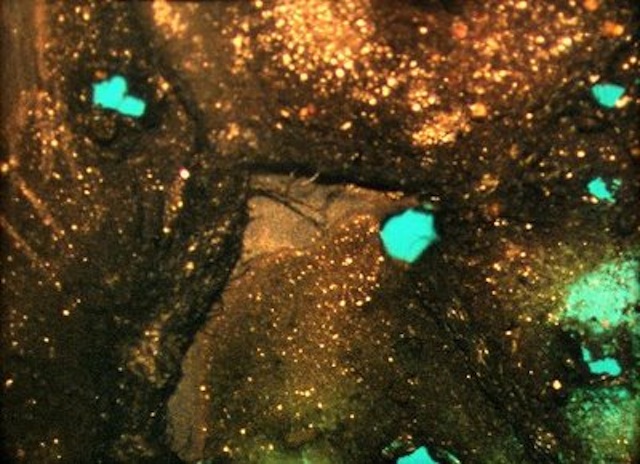

For Light Work I, Reeves shot her labor-intensive production of Light Work Mood Disorder using a digital macro camera before mingling this magnified view with documentation of the original performance film. Light Work Mood Disorder is very much of a piece with the aforementioned films contemplating decay: Reeves reworked crumbling institutional films by hand before setting the material back to chance in the double projection. Light Work I’s high-definition glaze, along with Anthony Burr’s droning score, gives tangible form to the distance Hoberman attributes to Cotton Candy’s documentation of the pre-cinema toys in San Francisco’s Musée Mechanique: “the DV of the future tenderly [regarding] the more human machine of the past.” Whereas the train and filmstrip in Trains are for Dreaming are intertwined as analogous technologies, the grainy microscope views and industrial footage contained within Light Work I are metaphorical figures. The hybridized nature of the piece gestures towards a certain ghostly persistence across technological divides: Gutenberg borrowed the calligraphic style of manuscripts for his printing press, and Final Cut still offers razor blade edits and cutting bins.

By fashioning a digital derivative of an unrepeatable performance piece that manifestly fails as documentation, Reeves creates an ambiguity about where and what the “Light Work” piece actually is that seems basic to the post-photographic moment Hoberman writes about. Reeves produced the digital transmission for the Voom HD Labs, a residency program hosted by the now defunct network of high definition television channels that put cutting edge technology in the hands of artists. Now it streams on Fandor—without such a leap, perhaps, as Reeves’s celluloid-based films. The concern, on the other hand, is that already marginal areas of film only become more so without a digitized conversion. If a post-photographic cinema is inescapable, how we remember what came before remains an open question.