Life imitates art.

Slaughtered in school.

and still no gun control?

How Come, Marco Rubio?

These three billboards, created by online activist group Avaaz, appeared outside of Miami, Florida after the umpteenth mass shooting in U.S. history. People want change, just like Mildred (played by Francis McDormand) did in Martin McDonagh’s Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, a film that follows an angry mother who demands answers when the police seem unable to track down the person who raped and murdered her daughter. Three Billboards did not exist by accident. It had to exist in this particularly divisive social climate. Following years of police brutality, of the voices of minorities struggling to be heard, and of people and politicians searching for answers to the issues that divide public opinion, there is a reason why Three Billboards has resonated so well. It feels familiar to many that have watched it. It feels current, despite its confrontational approach.

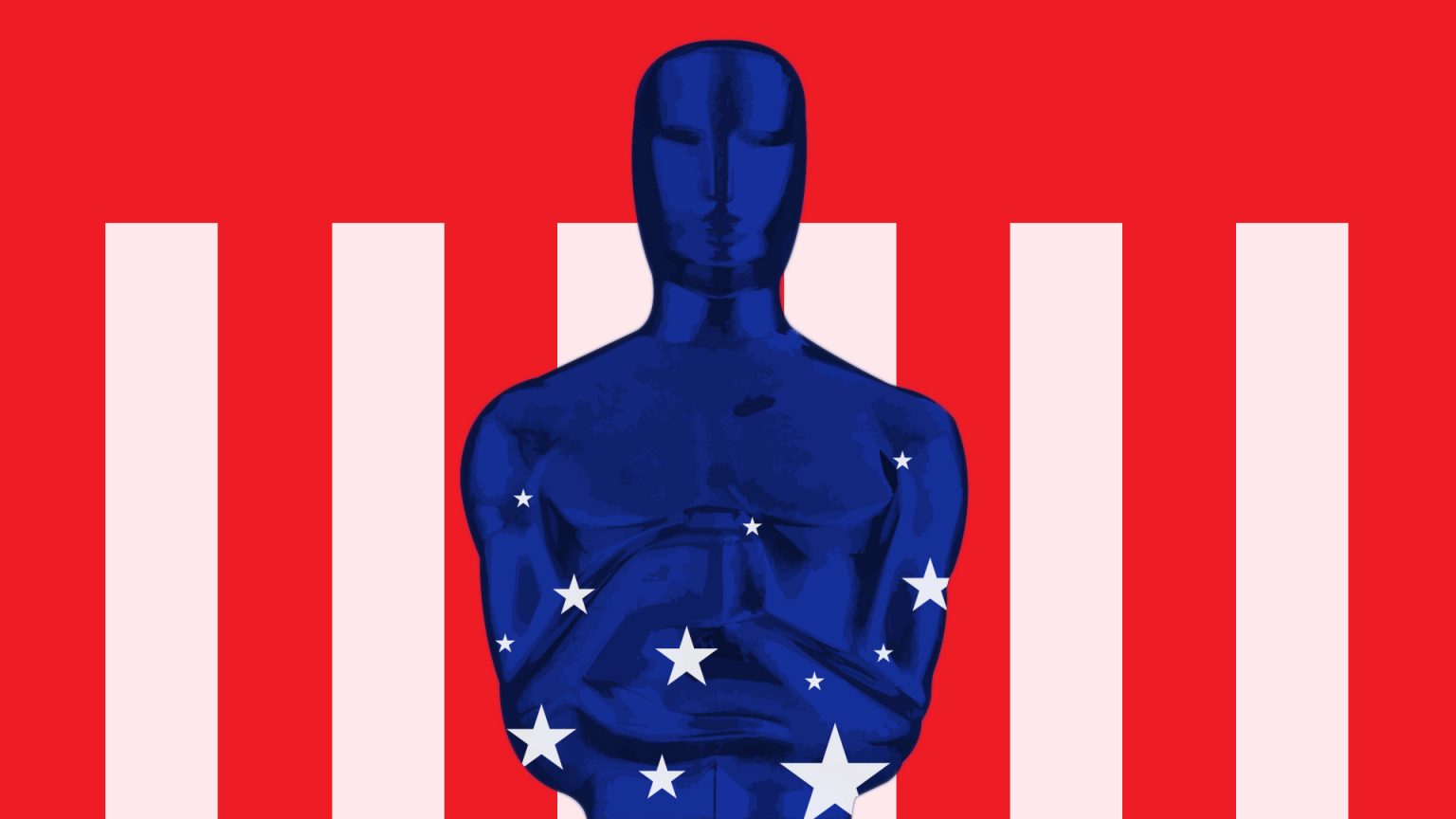

At this rate, it has a good shot at winning the top prize at the ninetieth Academy Awards. But even if it doesn’t, many of the other films nominated for Best Picture also contain the collective voices of change that society has been calling for. Lady Bird features the growth of a teenage girl told by a female director—a sad rarity. The Shape of Water features the marginalized communities of the 1960s as figurative and literal fishes-out-of-water banding together to be heard. Phantom Thread contains a female muse that refuses to be controlled by a man. Get Out turns the constant prejudices inflicted on many African Americans into psychological horror. And do we need to go into The Post’s statement on the current political climate?

It is worth noting that this is far from the only time the film industry (and the Academy Awards) have mirrored the U.S. climate of the moment. If anything, you can look at almost any of the Best Picture winners throughout the Academy’s history and pinpoint why a specific film won based on the events of the day. One should not go through the Best Picture winners in an effort to validate why those films won, but instead to understand the state of America (and the world) of those times.

Consider the Motion Picture Production Code as an example. For decades, mainstream filmmakers had to abide by a strict set of rules: Profanity, drugs, blasphemy, and even interracial relationships (amongst many other things) were not allowed in Hollywood productions. Some additional regulations included having to have a happy ending. Look at Elia Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement and take note of how “tossed-in” the ending seems. Things could not just be “okay” for protagonist Philip Green—they had to be glorious, with a reconciliation that makes little sense and that has aged poorly.

Fast forward to 1967: In the Heat of the Night wins Best Picture. Then Midnight Cowboy—an X-rated arthouse-inspired movie that details the struggles of a Texas gigolo—in 69 and The French Connection in 71. Sandwiched in between these films is Oliver!, which, for those who haven’t seen it, I will describe as an “inoffensive musical.” But other than that single anomaly these films signal the death of the Production Code, and the explosion of the controversial, edgy filmmaking that the world craved. At that point, television had become a household staple and John F. Kennedy and the Vietnam War were broadcast directly into homes. Movies like The Sound of Music could only cut it for so long.

Sure, cinema was affected by the other wars of the twentieth century, but those were different somehow. Casablanca was a triumph over evil by two distant lovers. The Best Years of our Lives championed positivity. Life kept going for Mrs. Miniver. But once The Deer Hunter and Platoon came around, Hollywood’s depictions of war became much “uglier.” No one “wins” in either film. There isn’t even the concept of “winning.” Sure, All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) is equally as dismal, but it was produced before the Hollywood code, and a number of years after World War I when the horrors of war did not feel like a bad omen.

In 54 and 76, with Republicans in office, Blue-collared underdog stories On the Waterfront and Rocky triumphed. The start of what we now describe as Oscar-bait (schmaltzy, melodramatic, and lengthy movies) began during the Reagan years (I’m looking at you Out of Africa, Driving Miss Daisy, and Chariots of Fire). George W. Bush’s years had a similar tone (Gladiator, Crash), while the Obama era mostly saw pictures that tried to defy these common rules (The Artist, Birdman, Moonlight). Though the insanely safe The King’s Speech also triumphed during Obama’s time (and against much better, daring films).

Now let’s look at (arguably) the most questionable winner in the Academy’s history: The Greatest Show on Earth (spoiler: it isn’t). People had assumed that High Noon was going to win. But the blacklisting of screenwriter Carl Foreman over his ties to Communism, mixed with the film being described as “un-American,” sent Academy voters into a panic. So the votes went to the stale Greatest Show, which has aged about as well as cheese on a hot sidewalk. Raging Bull similarly (and apparently) lost the Best Picture award to the underrated Ordinary People (it is not Raging Bull, but it is far from a bad film) because of an assassination attempt plotted by someone who was apparently inspired by Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. Movements in the world create nominees, and current events can easily change the tide—need we forget the boycotting that surrounded Zero Dark Thirty?

Is it fate that the only Western films to win (1931s Cimarron, 1990s Dances with Wolves, 1992s Unforgiven, and 2007s No Country for Old Men) won when a Republican was in office? What about pictures depicting marginalized communities winning when a Democrat was in charge? When it comes to popular films, especially those that get nominated and end up winning the Best Picture award, there are some repeating patterns that cannot be ignored.

There is a reason why the predicted winners, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, and The Shape of Water, have resonated so well. Yes, we can mostly agree that these are well-made films. However, they are also a sign of the times. Let’s not consider the Best Picture winners as the “best” films of their time, but rather as observations of what popular cinema, the U.S., and the world were like at the time.

Andreas Babiolakis is currently undergoing a Master’s degree in film preservation and collections management. He has a Bachelor’s in cinema studies and has devoted time to writing about film and music for over ten years. His Christmas is in autumn when the Toronto International Film Festival takes over his hometown of Toronto, Canada.