Lucia Puenzo‘s Wakolda focuses on a still controversial period of Argentinian history, when under the Peron presidency the nation’s officials welcomed German Nazis fleeing Europe. Among those attempting to evade the consequences of atrocities they’d committed during World War II was doctor, anthropologist and war criminal Josef Mengele, “Angel of Death,” famous for inhumane experiments conducted, among many others, on prisoners of concentration camps. Mengele fled Europe in 1949 and after living in Argentina and Paraguay, died in Brazil thirty years later, never facing the court of law. In Wakolda‘s plot Puenzo, who gained critical acclaim for her outstanding debut, XXY, once again focuses on the child psyche. The main character, young teenager Lilith, along with her family, develop a relationship with Mengele, who’s intrigued by the girl’s physicality and her pregnant mother’s “mysterious womb.”

Keyframe: How much is Wakolda‘s script rooted in reality and how much is it an artistic creation?

Lucia Puenzo: The script is composed of parts that are real and those that are fiction but could’ve been real. It’s a fact that Mengele lived in Buenos Aires for more than four years, knew Spanish very well, had a big pharmaceutical business and appeared with his own name in the telephone book. When the Mossad captured Eichmann, he flew to Buenos Aires, disappeared, and then one day re-appeared in Paraguay. So all that is true. Many history books confirm that he kept on doing experiments and conducted treatments on children and pregnant women using the growth hormone. He also worked as a veterinarian and even experimented with cattle—he had this obsession to make Argentinian cows breed twin calves. Also the character of Nora Edloc, the Mossad agent, is real. There were many Nazi hunters in Argentina at that time. There were also volunteers who weren’t even trained spies, just ordinary people. What is fictional is the family and the main protagonist, little girl called Lilith. My instinct was that such family could have existed and that he [Mengele] would’ve been fascinated by them.

Keyframe: What is it about this particular moment in Argentinian history that makes you want to explore that?

Puenzo: I have always been very much intrigued by not only why our and other governments opened their doors to millions of Nazis, but also how many hundreds of Argentinian civilians lived with those men, having them as neighbors, teachers or doctors without knowing who they were.

Keyframe: Some claim that Hitler never died, but also fled to South America. What do you think about this story?

Puenzo: Of course, when I was researching for this story there were many suggestions that he also was in Patagonia. And who knows? Some are so sure that they point at a house where he lived, others say he wasn’t even there. It’s in the terrain of myth.

Keyframe: Wakolda started with a novel you wrote. Was it clear to you from the very beginning that you’d adapt the book as a film?

Puenzo: No. I had no idea this is going to happen. But I kept on thinking there was something there, something interesting also for the cinematographic language—especially the contrast between spacious landscapes and tiny, close-knit community fascinated me. I like such contrasts.

Keyframe: How, on a practical level, did you prepare for this film?

Puenzo: It was a very long process, because first there was a novel that I spent almost a year writing in collaboration with historians, documentarians and people who lived in Bariloche. There are so many different aspects to it. First thing was to understand that German [that existed in Patagonia] community before the war, how [was it possible that] sometimes they were even more pro-Nazi then German citizens and after the war they were still ready to receive [fleeing] Nazis as heroes and help them ‘evaporate.’

Keyframe: What is it about the still-forming psyche of a child or a teenager that you are so drawn to?

Puenzo: Children at this age are becoming small adults, politically, ideologically and sexually. Everything is changing in them, even before they realize it and there is something very powerful about that process. I think what happens to my main character, Lilith, is very similar to what her brother says at the very beginning of the film: ‘What is it to change your skin?’ She’s becoming this little woman.

Keyframe: You have a pretty unique relationship with your cinematographer, Nicolás Puenzo…

Puenzo: He’s my small brother, so we’ve known each other forever. He was also my DP in XXY. We were talking a lot about how do we want to take Wakolda to the screen. We knew that we wanted to have a very quiet camera and, like I’ve mentioned before, a contrast between huge and tiny. This was our direction.

Keyframe: Is your sympathy for contrasts also a reason for choosing very suggestive, powerful music despite the above mentioned choice of very unintrusive camera work?

Puenzo: My musicians and my sound editor are the same in all my films and we are very close. I couldn’t imagine a classic from-the-period soundtrack for this film. I am a huge fan of Nick Cave or Warren Ellis of the Dirty Three and what they do. Also my musicians know them very well. There is something about their music that we use in the beginning of the film that reminds [me of] our folk music from Patagonia, the same instruments. And the more trash/rock music we use in the very end…it was some kind of an emotion we were looking for.

Keyframe: Your film is centered around the main character. Was it hard to find someone like Florencia Bado, a child who’d be able to carry the whole film on her shoulders?

Puenzo: It was a very long casting. We started seven months before shooting. We didn’t find anyone [appropriate], so we started going to schools. My casting director called me at a certain point and said: ‘I think I’ve found what we’re looking for.’ [Florencia] had never done any acting before but she wanted to be a part of the film; also her family’s support was very important. I think when you cast a child, you cast [the whole] family. They had to move to Patagonia—her parents, brothers, all of them. And actually they all act in the film. [Florencia] was very receptive. We trained her for six months. We’d meet three times a week and every day we’d only work on one scene. Her parents read the whole script and we told her a little bit about it. But she never knew what we were going to do exactly. She’d learn her lines a little bit earlier. She had a very close relationship with Àlex Brendemühl, which at a certain point started to worry us, because they were laughing all the time, and we were wondering: ‘how is she gonna show that she’s afraid of this man if they’re so friendly?’ But it helped her. She could act because she knew him very well.

Keyframe: You’ve decided to include this urban legend about the dolls in the film, and your character looks like a doll herself. Was this parallel intentional?

Puenzo: Yes. We though the same when we saw her for the first time. We were looking for that. Girls with big forehead, big eyes, small, skinny. She was perfect.

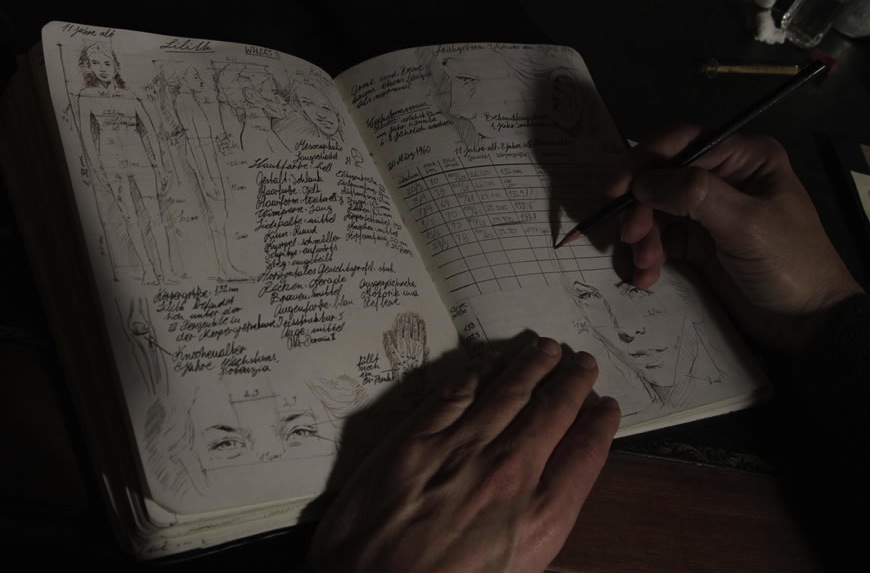

Keyframe: Can you tell us a bit more about Mengele’s sketchbook? It’s an amazing prop. Who created it?

Puenzo: The notebooks really existed, of course the ones we used [were not real]. But the information about them is well known and public. He was obsessed with writing everything down. One very well know documentarist who’s helped me with the book and then the film, had photographs of those. His [Mengele’es] drawings looked as if a child created them, they were very simple and schematic. For me it was the wrong direction. So we’ve decided to take a more anthropological direction with them.

Keyframe: You’ve decided to adapt your own book. Is this because you are very protective of your work? Could you imagine somebody else do it?

Puenzo: I think it’s a mixture of an experiment and a game. I really like writing scripts. In the process of writing the script it was funny when I realized that there are some parts of the book that cannot be translated onto screen—the most esoteric part of Nazism and what Wakolda hides in her womb…it’s very difficult to film, intangible. It works in a literary language but wouldn’t work on screen. So I tried another plot and that was fun. But I love the idea of my novels being adapted by other directors. Actually it is happening now, two of my books are being adapted.

Keyframe: Do you know what will your next project be?

Puenzo: I am writing a script for Mexican producers about Tina Modotti, and Italian-born photographer who then emigrated to Mexico. She’s had an incredible life. I’m focusing on the moment of her life when she is framed into murdering her partner, a Cuban revolutionary.

Keyframe: Talking about revolution—Jorge Rafael Videla just recently died. How did it make you feel?

Puenzo: He was one of the most hated leaders of the 1976 military coop, which is a completely separate process from the Nazi theme. He was the one that in fact invented the term desaparecidos. He was the one who one day said: ‘we didn’t kill 30,000 people. They are not here, there are no bodies. They are desaparecidos’ That was the most horrible, cynical way to say that. For us it was really important that he died in jail. We have a government today that is making them pay for what they did. Seven, eight years ago, they were taken to trial and convicted. Even if they are very old they have to die in jail, not in their houses.

Keyframe: Have you, with time, started to understand why was Argentina so open to war criminals at the time?

Puenzo: It was kind of different in various countries. For example in Argentina and Paraguay, the presidents of that time—we had Peron, they has Stroessner—they were both raised as military. Peron was representing the center-left, and had many progressive ideas and was good for the people, but this [allowing the Nazis to come to Argentina] is an issue that even the best peronistas cannot explain. He opened the door to many Nazis, German militaries trained Argentinian ones, there was also a lot of Nazi-gold involved. Something similar happened in Paraguay. It’s a very, very complex issue.

Keyframe: You are a filmmaker and a writer. If you got invited to a film festival and a book fair at the same time, what would you choose?

Puenzo: A book fair, definitely. The world of literature is more quiet. Doing it is much more fun. Books also have longer lives. You can have a book in a library for five years and it’s gonna find the reader. It’s also cheaper, so there’s no tension involved, you can take your time. It’s not all about success. And probably, in the literature world, if you meet the authors, they’re gonna speak about literature. If you meet with film directors on the other hand, they’ll speak about funding. My husband is a writer, we meet with writers every day…So there’s something about it that feels just more…mine.