This video was made in the days immediately following the 2013 Flaherty Film Seminar, one of the most unforgettably exhausting experiences of my life. There, in the Seminar’s pastoral confines in Colgate University, I spent seven days of watching, discussing and thinking about filmmaking from morning to night. Then I travelled halfway across the world to embark on a summer film project. In one sense the timing was perfect because I came away from the Seminar with a renewed sense of purpose in thinking about film’s relationship with the world, as well as the moral and political implications behind every creative decision. On the other hand, launching from such an intensive, hermetically sealed intellectual environment into the outside world was almost too much to process. It is said that people take months or even years to recover from their Flaherty experience, as the rigorousness of the debates and the thorough dismantling of one filmmaking approach after another can leave one utterly disoriented in determining which practices make sense.

This conflict between theory and action was central to this year’s Flaherty, whose theme, proposed by curator Pablo de Ocampo, was “History is What’s Happening.” It’s a phrase whose seeming contradictions played over the course of the week, as we watched film after film that either embodied or critically examined vital cinematic artifacts of history, particularly those in danger of being neglected or forgotten. That crisis of losing led to another crisis of remembering: what’s at stake when we try to bring history back to present consciousness? What aspects of the past do we risk distorting or defiling even as we try to preserve and reinvest them within our own moment?

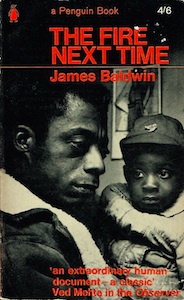

To explore some of these questions, this video depicts my own processing of the Flaherty experience, centered on a handful of quotes taken from the discussions. First is a passage from James Baldwin’s extraordinary essay “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation,” a deeply moving reflection on the history of black experience in the U.S., which the entire Seminar read aloud on its first night. It was a somewhat unnerving spectacle to have a room of 150 people, mostly white, recite a text that expressed dismay over white America’s ongoing failure to comprehend black lives. These somewhat confounding racial dynamics were eventually brought out into the open by Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich in a moment that I quote in the video, though in a different session conducted by the activist group BLW (discussed further below).

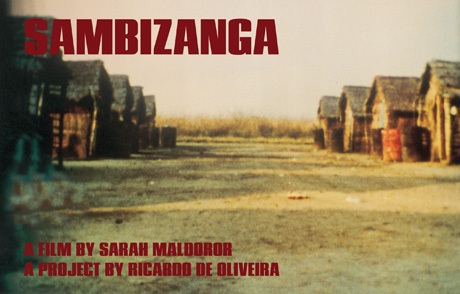

Such dilemmas, which underlie how experiences get transmitted or transmuted across time, space, personal identities and audiovisual media persisted in everything that we watched and discussed. We were further enraptured by the recovered archival video of a stirring speech by activist Queen Mother Moore to black inmates at Green Haven Prison in 1973. Equally cherished was the presence of seventy-five-year-old Sarah Maldoror, who in 1972 became one of the first woman to direct a feature in Africa with the seminal Sambizanga, about the imprisonment and torture of Angolan freedom fighters. As stirring as these were to witness, we had to question, what exactly do we take away from them? Are they objects of archival or aesthetic appreciation? Leftist nostalgia? Theoretical dissection? Inspiration for present day action?

By the second day, filmmaker and Flaherty board member John Gianvito remarked on a recurring theme in these films: imprisonment, not only physical but intellectual. The implied follow-up question: how might we as filmmakers and viewers break out of such walls? To what extent does it purely involve thought, and to what extent does it require action? This inquiry reached its peak point two days later, with a group exercise led by the activist group BLW, in which the whole Seminar was made to recite the transcript of a viral video by Egyptian activist Asmaa Mahfouz that helped spark the 2011 protests in Tahrir Square that galvanized the Egyptian revolution. The exercise, intended to help its participants draw direct inspiration by reenacting a work of media activism, inspired a near-revolt of its own within the Seminar. The range of negative reactions included: reluctance to being coerced into a non-spectatorial role in the program; disapproval over the highly regimented, step-by-step procedure of the exercise; and offense at the notion of co-opting the media of others for what one participant labeled “something to have a campfire around.”

I found this collective discomfort to be the most revelatory moment of the Seminar. For me, the critiques revealed as much of their own underlying assumptions as those of BLW, especially in expressing the Seminar proceedings’ general privileging of critical spectatorship over committed action. Some respondents articulately defended viewing media as a productive, non-passive critical act in its own right (this is something that I would implicitly agree with, given how the vast majority of video essays that I’ve produced implicitly demonstrate this thesis). In contrast, critical voices found BLW’s mission to re-embody activist media too literal and simplistic, to the point of being offensively patronizing to its source materials.

To these and many other criticisms received, BLW co-founder Sarah Lewison offered an extended, exasperated defense that reflected the state of someone pushed beyond her comfort zone further than just about anyone in the Seminar while attempting to reconcile her position with everything directed against it. They were the words of someone trying desperately to work their way towards a breakthrough understanding that could somehow clear the cobweb of conflicting interpretations woven around her work. The moment exposed what I humbly submit as a fallacy behind the operating philosophy of the Flaherty Seminar, originally espoused by its founder Frances Flaherty: this concept of “non-preconception,” a utopian state of ideological blankness in going about the process of observation, discovery and artistic creation. The BLW exercise outed a whole roomful of pre-conceptions held by a host of smart people. Lewison’s remarkes tried valiantly to acknowledge these prejudices if only to somehow incorporate them, and thus enrich her own pre-conceptions behind her practice.

In that spirit, this video is dedicated to Lewison, to BLW, and to the Flaherty Seminar for all the lessons they offered in the ongoing struggle to transmit, to receive, to internalize and to somehow act upon human experience and thought. It’s worth pointing out that some of these quotes in their own way are quasi-recitations of received ideologies; this is most apparent in John Gianvito’s quote, which itself quotes from Noam Chomsky and one other source. (I hold John in the same regard that I think he holds Chomsky, so reciting his words carries a personal significance). It brings up something introduced in the Seminar discussions by artist Jean-Paul Kelly (who quoted from the work of scholar David Rodowick): how ideas, behaviors, cinema and media are a network of vectors that are transmitted like viruses among us and that recombine within their hosts, leading to mutant versions of what came before.

In envisioning my own mutant version of Lewison’s monologue, I wanted to find a way to express the same feeling of being isolated, misunderstood and out of place that I perceived when she first extemporized those words, to connect to the core sense of fortitude in the midst of being overwhelmed that I found so moving. Needless to say, there’s something fundamentally inappropriate about this method in terms of where and how I try to reapply her experience, but somehow revealing as well, in terms of how what little sense there is to the language, rhetorical gestures and ideological concepts she used when uttered aloud in a place where no one can possibly understand them. That itself illustrates a huge disconnect between the highly conceptual discourse of the Flaherty and the “real world”, a chasm that I now find myself trying to straddle.

This paradox of accessibility and inaccessibility is embodied in some way by the Seminar proceedings. The Seminar is conducted in a largely confidential environment so as to foster as much intellectual openness among its participants as possible; as a result, recording and reporting of its proceedings tends to be very limited. In that regard, I thank the Flaherty staff and board for approving this video and report. If I had more time and space, I’d write more about all the other filmmakers, listed below, whose works and remarks during the Seminar offered just as much provocation. Credit goes to the seminar staff and programmer Pablo de Ocampo for presenting this thoroughly cohesive and complementary selection of artists:

Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc

Basma Alsharif

Sirah Foighel Brutman & Eitan Efrat

Alexis Cordesse (in absentia)

Kodwo Eshun of The Otolith Group

Robert Flaherty (in absentia)

John Grierson (in absentia)

Jean-Paul Kelly

Michel Khleifi (in absentia)

Sarah Maldoror

Chris Marker (in absentia)

Wendelien van Oldenborgh

The People’s Communication Network (in absentia)

Eyal Sivan

Deborah Stratman

Joyce Wieland (in absentia)

I should also acknowledge that I enjoyed the privilege of participating in the Seminar as part of the Flaherty Fellowship Program, which offers support for students, filmmakers and professionals to attend the seminar, through financial assistance and mentorship during the program. For first-time attendees like myself, it’s an invaluable opportunity to experience the seminar, as it offers a peer network of fellows who have special opportunities to interact with Flaherty staff and filmmakers, support that’s most welcome throughout this thoroughly mind-battering experience. Information on the Fellowship can be found on the Flaherty website.