“Humans have an intuitive drive to find causes,” says Noam Chomsky in Michel Gondry’s Is the Man Who is Tall Happy? Before delving into this film, and the others of the 64th Berlinale, let’s give Chomsky’s observation some thought in terms of its relation to film festivals. Critics, myself included, tend to search for meaning in the madness of screenings—especially when, in the case of this festival, there are 409 movies being shown in the span of ten days. Despite rationally knowing more often than not there is no real guiding force, this urge to draw connections between films is understandable, as it gives purpose to the time spent (sometimes wasted) in dark rooms disconnected from the rest of the world. (I have yet to hear the word “Sochi” spoken within a mile radius of Potsdamer Platz.) But looking for a connective thread can also detract from the spontaneity found in confusion—and anyone who has been to Berlinale can tell you confusion is central to this festival experience. As such, I entered Berlinale with no intention of finding a theme and instead opted to embrace the immersive present moment in all its chaos. Or, to squeeze out one more quote from Chomsky, relish in a “willingness to be puzzled” by what was about to transpire.

Always interested in questions of national guilt, I skipped the red carpet bait of the World War II drama The Monuments Men and sought out The Airstrip—Decampment of Modernism, Part III. In this third part of Heinz Emigholz’s architectural film series, the director explores the question of what it means, as German of a certain age, to owe his life to the atomic bomb; that is, the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that subsequently ended WWII. As explained in voiceover (Natja Brunckhorst narrates), Emigholz approaches capturing reality through the lens of a radical present: time is conceived of as the moment after a bomb is dropped, but before it hits its target; a moment that is neither the future (what will come is known) nor the past (the destruction is still impending). Composed of static shots of buildings, memorials and public spaces in Berlin, Buenos Aires, Rome, Saipan and other locales, Brunckhorst relates their histories in a detached tone. The simple monologues perfectly illustrate how physical space is constructed not just by steel and concrete, but also by nationalistic and historical narratives. Ending back in Berlin after a journey to the site where Enola Gay and Bockscar took off for Japan in 1945, the narrator asks if the film is an attempt at impossible atonement or merely artistic indulgence. The question remains open, but Emigholz’s film ultimately posits that the past, guilt and complicity will always linger in the physical places we inhabit.

Jumping back to the opening night film—embrace the confusion, please—to my own surprise, I was moved by Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. Fans of the director’s distinctive lavish production design and use of sprawling all-star casts will not be disappointed, but the movie amounts to more than the sum of these superficial parts. Indeed, more than any of Anderson’s other works, Grand Budapest resonates on a deeper level, exploring how melancholia is inherent to the art of storytelling.

Grand Budapest’s narrative is almost comically convoluted, being structured much like a matryoshka doll. Beginning with a young girl paying homage to a nameless author at his memorial (the aged scribed is played by Tom Wilkinson; the younger version by Jude Law), the film then jumps into the storyline of the book she carries with her: said author’s retelling of the adventures of the hotel’s owner, Zero Moustafa (old: F. Murray Abraham; young: Tony Revolori). Here the film begins in earnest, with an elderly Moustafa relating in flashback his escapades with his mentor, Gustave (Ralph Fiennes), to our attentive young novelist. Though complexly layered, this setup never feels forced, as Anderson’s hyper-stylized visuals perfectly complements it: at every turn, the emphasis remains on the act of transforming the past into a story. Given this, Grand Budapest earns its nostalgic sadness. Like any myth, the Grand Budapest Hotel can only be known through memory, leaving those in the present—from Moustafa, to our novelist, to maybe even Anderson himself—yearning for something that can never be attained.

As it has to be done, I’ll now deal with the bad: Yann Demange’s ’71. Set in Northern Ireland in the titular year, the Competition film follows a British solider (Jack O’Connell) who is left behind enemy lines in a Catholic neighborhood. As he attempts to get back to his barracks, he is aided and threatened by Protestants and Catholics alike, proving all sides of the conflict to be equally kind/terrible. But instead of conveying complexity, all this amounts to is a pandering universal tale that is stripped of any historical specificity or politics. To be blunt: this is the least courageous form of filmmaking; one that avoids choosing any side in favor of an abstracted ideal of the human spirit. As the credits rolled, my mind went immediately to Ken Loach, who is receiving an honorary Golden Bear at the festival this year. In contrast to this director’s body of political cinema (especially 2006’s The Wind that Shakes the Barely), ’71’s broad reduction of hundreds years of colonial history to serve a self-congratulatory tale of “humanity’s ability to rise above” was all the more grating.

In the Panorama section, two films stood out: Tsai Ming-liang’s Xi You and Gondry’s Is the Man Who is Tall Happy? The former is a slow travelogue, composed of abstracted close-ups of Denis Lavant’s weathered face and long takes of a Buddhist monk (played by Lee Kang-sheng) walking through Marseille. Drawing out each step for minutes on end, the monk barely moves, but remains the constant focus of every scene. Lavant eventually joins the monk on his “stroll,” mimicking his molasses-like pace. Xi You thus emphasizes the seemingly contradictory notion of the action involved in slowing down. In one ten-plus minute shot, the monk descends stairs into the metro while passers-by rush past him. Only one young girl pauses to watch the monk’s laborious downward climb, subsequently (and unconsciously) pausing in the process. (Indeed, Xi You had a similar effect on me.) Utterly beautiful in its simplicity, the film envisions another kind of temporal space, where time is measured in deliberate, paced movement and not linearly.

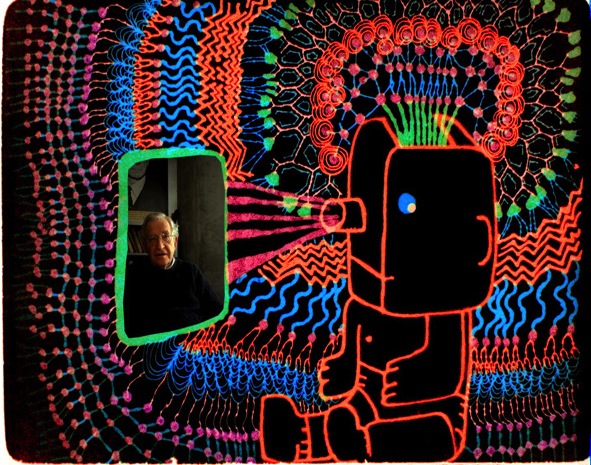

As for Gondry’s documentary, the film is a labor of love—and labor truly is the operative word. Shooting on a hand-cranked Bolex camera, Gondry interviewed Chomsky and then, over a period of four years, animated the conversations with hand drawn sketches and stop-motion. While at first the drawings seem far too simplistic to be suited to the renowned linguist’s theories, the form ultimately suits the content. In choosing not to use concrete reality in favor of animation, the documentary itself becomes something of an experiment in representation, challenging the referential power of language. But the doc is not all heavy philosophy, as Gondry also asks Chomsky about his upbringing and relationship with his wife, Carol. Only when she comes up does Chomsky stumble, graciously refusing to talk about her death, proving some things remain beyond language.

So what, then, is to be made of this small sampling of films screened during the first half of fest? Perhaps it was the fact that I caught the Chomsky doc earlier on, but his reassurance about not needing to put any stock in a guiding agency—be that fate, god or a festival programming team—made this Berlinale experience comforting in its aimlessness. If all we have is the present before we turn to dust, then the time spent with some good cinema is enough. Or, at least, this is all we have.