Iranian cinema has a history of couching its criticisms of life in Iran in metaphor. Mohammad Rasoulof‘s 2009 The White Meadows offered the oppressive, authoritarian culture of contemporary Iran as a warped Gulliver’s Travels through a lifeless salt marsh of islands out of some surreal medieval world. What’s most startling about Rasoulof’s Manuscripts Don’t Burn is its audacity in projecting a portrait of the authoritarian regime in direct, confrontational terms. Opening on a contract murder that plays like an American gangster picture dropped into dusty slums outside Tehran, the film takes a circuitous route to outline the workings of a totalitarian state that intimidates and terrorizes its intellectuals and dissident writers. Along with the web of writers connected by censored and suppressed works, we follow the thugs doing the dirty work for a vicious minister, including a man whose motivation is simply money to pay for his son’s operation (it’s not a corny as it sounds). He’s constantly stopping along the route to see if the money has reached his account, interruptions that keep the political horror story firmly framed within the banalities of everyday life.

The script is overly complicated, stirring in characters who appear without introduction, and a little repetitive in the second act, but it seems churlish to complain that such a provocative, covertly-made portrait of the Iranian government as a brutally repressive regime could “use a little cutting.” The confusion sorts itself out as the intimidation turns into outright terrorism, 1984 by way of The Godfather, while an inspired formal twist puts the whole ordeal on continuous loop, a cycle of never-ending despotism. I found echoes of The Lives of Others in the routine surveillance of citizens, but this is more confrontational and brutal and Rasoulof hasn’t the safe distance of exploring a fallen regime. His targets are current and he puts a target on his chest for this. For that reason, he’s the only artist on the film who takes credit; the other names are hidden for fear of reprisals (we assume the actors are expatriates safely out of country). As of now, his passport has been revoked and he is unable to see his family, whom he has already moved out of country. That’s some sacrifice.

Trapped, also of Iran, is a more conventional thriller that opens with a sense of optimism and possibility, thanks to a groovy theme song from Cat Stevens. Nazanin Bayati is a first-year medical student in need of housing (the dorms are full) and Pegah Ahangarani is a fast-living salesgirl with a spare room and manic-depressive symptoms. It seems headed for psychological drama, an Iranian Single White Female maybe, until Ahangarani is arrested for debt and Bayati and ends up tangled with a gangster loan shark. She’s the classic victim—idealistic, trusting, good-hearted and loyal (Ahangarani’s good-time pals are quick to cut her off once she’s in trouble)—but also strong-willed, committed and persistent. While it’s less overtly political than Manuscripts Don’t Burn (and really, what isn’t?), the debt is tied to gray-market payoffs for emigration papers and filmmaker Parviz Shahbazi suggests an entire predatory industry around the process. The black market loans are simply a left-handed form of government graft honed to corporate efficiency, a theme we’ve seen creep into other Iranian imports (A Respectable Family, Rasoulof’s Goodbye). But ultimately it is a kind of horror story and Bayati’s ordeal becomes terrifying as things spin out her control faster and farther than she can grasp. Even the mercenary pals who cut Ahangarani loose so quickly are moved to help out, if only a little. It’s not all bureaucratic intransigence and free-market predation. Just mostly.

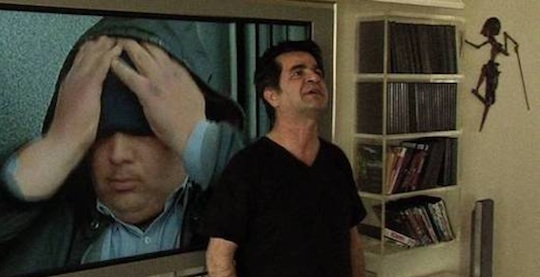

I left the 2013 Vancouver International Film Festival before the gala screening of the Paris-set-and-shot The Past (France/Iran), Asghar Farhadi’s follow-up to his Oscar-winning A Separation with Bérénice Bejo and Tahar Rahim (Kristin Thompson’s coverage, along with other Middle-Eastern films at VIFF, is here), but Jafar Panahi’s Closed Curtain added to the political defiance of the Iranian section. His second film made while under house arrest, co-directed with Kamboziya Partovi and shot in his villa on the Caspian Sea, it’s all very allegorical, with a writer in a police state hiding out with his dog (now outlawed under Islamic law), a suicidal young woman, and Panahi himself. The filmmaker’s entrance sweeps these characters into the realm of fiction, like the ghosts of films unmade rattling around his imagination. The film feels more like a sketch or an internal debate than a fully realized film, but it’s still remarkably effective, and it’s no coincidence that even as Panahi steps outside of his home, the camera never leaves the villa.

It’s hard to remain a Marco Bellocchio booster when his output is so variable, yet he seems to manage at least one unqualified jewel a decade, that last one (by my reckoning) Good Morning, Night back in 2003. Dormant Beauty (Italy), a sober look at the collision of politics, religion, and pious protest based on a real-life controversy from 2009 in Italy (with echoes our own Terri Schiavo ordeal), is Bellocchio back in fine form. A family chooses to remove a woman from life-support after 17 years in coma and the Catholics rise up in protest. This is the Berlusconi era and, while that real-life figure is offscreen, he orders his party to vote in sympathy with protesters (because it’ll play well in the media, not out of any conviction), which doesn’t sit well with newly-elected Senator Toni Servillo. There are a lot of passionate people in this drama (Alba Rohrwacher as the Senator’s daughter, Isabelle Huppert as the mother of another girl in coma), but they are as angry, desperate, damaged and/or self-servingly pious as they are committed to the cause. Bellocchio doesn’t pass judgment when Rohrwacher abandons her protest group for a fling with a charming guy she meets in the protest crowds—if anything, he lets us see this from her POV, meeting a possible soulmate and giving in to overwhelming desire with a swoony rush—but it does put it all into perspective. So many are so focused on the sleeping dead that they forget about the living. The contradictions in these characters aren’t complex but they are deep and Bellocchio invests them with the weight of faith and honest emotion.

From Manoel de Oliveira, still alive and well and making movies at the age of 104, comes Gebo and the Shadow (Portugal/France). I find the mix of his dry sense of humor, dramatic understatement and delicate imagery quite lovely and his late films are like perfectly sculpted short stories. Based on a Portuguese play (quite famous in Portugal, apparently, but unknown to me), this chamber piece plays out with an almost anachronistic theatricality in its performances, not declamatory but measured, studied, slowed to a careful thoughtfulness as the characters (Michael Lonsdale as the overworked accountant Gebo, Claudia Cardinale as his wife, Leonor Silveira as their daughter-in-law) debate morality, honesty, responsibility, ambition, and sacrifice like philosophers. That’s another trademark of late Oliveira, those long salon conversations taken at a leisurely stroll, but they have more immediate impact when their criminal son (Oliveira regular Ricardo Trêpa) returns home. This is a somber chamber piece (with brief respite thanks to cheery visits from Jeanne Moreau and Luís Miguel Cintra) and Oliveira shoots it with a closed-in intimacy. It’s not so much claustrophobic as oppressive—they are as trapped in the frame as they are in their lives—and he barely moves his camera or cuts back from his tight master shots, taking in scenes as if they were paintings. And, oh, what a canvas, with rumpled, weary figures against cold stone and warm candlelight. The themes are right on the surface but, for all the careful dialogue and measured deliver and spare, precise décor, so is the humanity of these tired survivors.

Under the Rainbow (France) reaffirms my affection for director / screenwriter Agnes Jaoui. It’s her best film since her debut A Taste of Others (2000), which was also written with longtime partner and co-star Jean-Pierre Bacri, and they get the plum roles here, she as a flustered divorced mother trying to advise a younger sister in a whirlwind romance, he as a gently peevish divorced father with no paternal instincts and a new girlfriend with two young daughters. As the title suggests, there’s a play with fairy tale situations in the material world, including romance that opens with a playful flip of Cinderella and a darkly charming prince (Benjamin Biolay) who turns out to be more big bad Wolf (it’s also his name, for those slow on the uptake). But Jaoui and Bacri are best with flawed characters fumbling their way through relationships and frustrated lives and this is full of them, lovingly captured in all their imperfections, fears and minor triumphs. Many will find this slight and I won’t contradict them, but I appreciate Jaoui’s optimism and appreciation for guarded folks who are inspired to take a chance on love or take a stand for friendship.

Juliette Binoche plays Camille Claudel in middle age, committed to an asylum, in Bruno Dumont’s Camille Claudel 1915 (France). As Camille, famed sculptor and one-time lover of August Rodin, she is an anxious storm of anger and loss, racked with paranoia (she’s convinced that Rodin and his cronies are engineering her imprisonment and trying to poison her), but her greatest loss is not freedom but the ability to express her artistic drive and she is lucid compared to the other, seriously mentally challenged inmates. Her expression reveals an instinctive revulsion for these fellow patients, no doubt in part for the implicit suggestion that she is one of them, but also a compassion when she faces not the patient but the vulnerable human in need of help, and the staff knows it, trusting her look after one or another at times. There’s a savage duality in so many of Dumont’s characters and cultural collusions from previous films but here there’s caring and compassion, at least until the film shifts to her brother Paul (Jean-Luc Vincent) and the insufferable piety that commits service to God at the expense of those on earth.