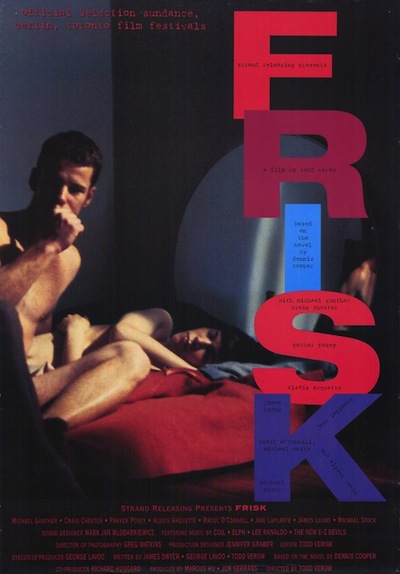

“I am not interested in playing it safe,” says maverick indie filmmaker Todd Verow with characteristic aplomb, and who would ever want him to? Decrying mainstream cinema’s lack of risk-taking, and championing reckless creativity over commercial prospects, Verow remains a fiercely iconoclastic force to be reckoned with nearly twenty years after first making his bloody, sticky mark with the highly controversial adaptation of Dennis Cooper’s hallucinogenic serial-killer novel Frisk, the infamous premiere of which caused an uproar at the San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival and garnered its bad-boy writer/director death threats.

In those heady days Verow was a fellow traveler with the directors of New Queer Cinema, a term coined by sage critic B. Ruby Rich to describe the burgeoning movement of visionary works by Tom Kalin, Todd Haynes, Gregg Araki and other gleefully nonconformist filmmakers who applied daring aesthetics and radical politics to sex-positive stories. In subsequent years Verow has remained an artistic force, one who always goes for the jugular, making dozens of films at a rapid pace through his production company Bangor Films (with partner in crime James Derek Dwyer), shooting with whatever tools and tales are at his disposal, and baring naked bodies and liberating ideologies with equal fervor.

From the teenage travails of Vacationland and the art-school hijinks of Between Something and Nothing to the urban angst of Little Shots of Happiness and the addiction chronicles of Deleted Scenes, Verow’s films traverse tricky geographic and emotional terrain, far from the comforts of the multiplex. As Verow wrote in his 2009 manifesto “No More Mr. Nice Gay,” written for the Berlin Film Festival Teddy Awards, “Aren’t you tired by now of these buff, shiny, happy, pretty pretty gay people in ‘alleged’ comedies about hooking up and being shirtless and oh-so-pretty and oh-so-vacant. No more documentaries about gay marriage and about ‘how just like everyone else’ we are.” Verow and his characters are decidedly anti-assimilationist, and it was from this refreshing perspective as an articulate outsider that Verow recently considered his career, the legacy of New Queer Cinema and eco-conscious filmmaking in a wide-ranging conversation with Keyframe.

Keyframe: You’ve been based in New York for quite some time now. Are you as enthused about the city as ever, and do you feel a part of a particular film culture there?

Todd Verow: I do love New York. I moved here in 1989, right after college, and despite some short and not-so-short detours in other cities—San Francisco, Boston, Providence, Berlin—it is the place where I feel most at home.

But it is changing. I know New Yorkers are always complaining, ‘Well, it used to be…,’ but the city really has reached a breaking point where it is no longer possible for young artists to afford to live here. When even the spoiled trust fund babies have to move to Bushwick, you know there is a problem. When older artists are being forced out and younger artists have no way in, then a city is culturally dying. Seemingly overnight there is a 7-Eleven on every block. I mean, WTF?

As far as film culture goes New York still has a great deal to offer, although its lack of a major film festival such as in Cannes, Berlin or Toronto is baffling. Sorry, but the New York Film Festival is a joke and Tribeca has never taken off. There are some great smaller festivals but they are all struggling to survive.

Keyframe: You still manage to cross the pond fairly often, yes? What have you been working on in London, and is another sojourn to Paris in the works? You really captured the City of Light’s élan in Bad Boy Street.

Verow: I travel to Europe quite often for film festivals and screening, and I get inspired and then usually go back and make a film. I am co-directing a documentary in London with Charles Lum about the leather bar The Hoist. I have made three films in Paris so far—Bad Boy Street, The Final Girl and The Boy With the Sun in His Eyes—and I have been talking to Yann de Monterno, the star of Bad Boy Street, about making a family comedy there.

Keyframe: Reviewing your filmography, it’s hard to believe that nearly twenty years have gone by since Frisk.

Verow: I know, it’s hard to believe it was so long ago. I was so young, naïve and cocky when we started making Frisk. It was hard work but we had a blast making that film. It was incredibly liberating for me to work from someone else’s source material for my first feature. Everyone said the book was unfilmable, and I love a challenge, so I said yes.

When the film came out we didn’t really know what to expect. The negative reactions were extreme. The interesting thing was that most of the extreme negative reactions concerned things that weren’t actually in the film. That is when we knew we had succeeded in getting inside people’s heads and truly disturbing them, as it should be. That is what I am most proud of with that film: There is no redemption, no way in or way out for the audience.

After the dust settled from Frisk I knew I needed to make something more personal, more intimate. I was also interested in improvising and filming a fiction film as if it was a documentary, so I immediately started shooting Little Shots of Happiness.

Keyframe: With these early works you helped usher in the New Queer Cinema movement. Did you embrace the moniker at the time, and do you think that the movement delivered on its early promise?

Verow: I did embrace it at the time and I greatly admired all of the New Queer Cinema filmmakers. I worked with Gregg Araki on Totally Fucked Up, I knew Todd Haynes from Brown University, I met Tom Kalin at the Swoon premiere (where I also first met Craig Chester, who I then insisted on casting in Frisk). It was an exciting time and very interesting films were getting made. It felt like a community. But while the films got a great deal of attention and praise, it was hard for any of them to make money. As the ‘independent’ film world exploded around the same time, the thinking was to go bigger. But when you go bigger the risks are greater and rough edges tend to get smoothed over. Before you knew it all the things that made New Queer Cinema interesting were gone. Don’t get me wrong—the filmmakers are all still doing good work, but that desperate punk energy is gone.

Going bigger was never really an option for me. I had some offers to do things, but I wanted to do them my way. I would have meeting after meeting with producers and they wouldn’t go anywhere. So I figured I would go smaller, take even more risks, shoot an improvised feature on Hi8 video, make a movie with a cell phone camera, be experimental. I am not interested in playing it safe.

Keyframe: LGBT films, and the audiences for them, certainly have changed since the early nineties. I see far less radical work now. Has queer cinema become too mainstream for your tastes?

Verow: There are a lot of risk-taking, controversial, experimental LGBT films being made but there are also way to many mainstream queer films, which tend to be slicker and have higher production values. The problem is that festival programmers tend to select the mainstream films. This isn’t true just of queer film. Overall, fewer interesting indie films are included in festivals, while challenging, experimental, interesting films don’t get programmed. Festival audiences have been dulled for far too long with ‘safe’ crap.

Keyframe: Is this at least part of the reason why you’ve embraced digital distribution of your work?

Verow: I am very excited about digital distribution. I like the idea that my films are out there, in the ether, waiting to be discovered by anyone around the world. It’s great to get feedback from people who have seen the films, people who would never have a chance to see my movies in a cinema or even on home video, but who have discovered them by chance online.

Keyframe: Some of your most clearly autobiographical films, such as Vacationland, in which you go back to your teenage years in Bangor, Maine, and Between Something and Nothing, which draws on your art-school experiences, are online and reaching all sorts of viewers. In revisiting your past, are you perhaps exorcising demons?

Verow: I wrote both of the scripts while I was living in Berlin. Something about being so far away from home helped me tune into those times. It was quite cathartic, the scripts just came out of me. I felt like I needed to let these demons out, to free them and make room for new demons. We run into trouble when we kid ourselves into thinking that things from our past didn’t really happen or don’t still affect us.

Keyframe: With their autobiographical revelations and unabashed sexuality, I think of your films as being unusually naked.

Verow: I have been accused of being a narcissist and an exhibitionist, which is kind of ridiculous because I usually look terrible in my films. I wouldn’t really call it exhibitionism when I step in front of the camera, because I become someone else. I like playing bad guys, which gives me a chance to explore a side that is so different from who I really am. Also, I usually end up doing the more extreme scenes myself because it’s easier than convincing another actor to do them, and in a way that their character would do them, and most of the time that isn’t pretty.

I’ve always found nudity to be incredibly liberating, and I find it odd when an actor has issues with nudity. The first lesson actors should learn is how to use their body as an instrument. The hardest thing about doing sex scenes is getting the actors to relax, getting them to stay in character and be in the moment. I always shoot a lot more than I am going to use—I tell my actors this—and I know the moments that I’m looking for and how I’ll need to edit them together, and I just keep shooting until I get what I need.

Keyframe: I’ve developed crushes on at least two of your characters: Wolf in Deleted Scenes and Claude in Bad Boy Street. The actors in these roles were great finds, and Bonnie Dickenson is equally striking in Little Shots of Happiness. How do you approach the casting process?

Verow: I often like to work with the same actors because we understand each other, but I also like to discover new people and work with non-actors. Getting different points of view from different people is always exciting.

I cast Ivica Kovacevic, who plays Wolf in Deleted Scenes, through an open call. It’s a tricky part because so much of his character is conveyed through subtle guardedness, but Ivica has this perfectly expressive face and with just one subtle movement you can see his defenses start to crack. That is a joy to watch.

I’ve known Yann de Monterno for a long time, and I wrote the character of Claude in Bad Boy Street with him in mind. I knew he would be great and he didn’t disappoint.

I worked with Bonnie Dickenson on Jon Moritsugu’s Mod Fuck Explosion and Terminal USA, for which I was the cinematographer, and I loved her as an actress. I came up with the idea of Little Shots of Happiness with her in mind, and she really connected with that character. As we went along we were able to communicate almost telepathically. I would just give Bonnie a look and she would know what I meant and adjust her performance. It really was an amazing experience and I am so proud of Bonnie’s performance in that film.

Keyframe: You’ve maintained an amazingly prolific output for nearly two decades now, with no signs of slowing down. Are you happiest when you’re working?

Verow: I do love making movies, so yes, I do believe I am happiest when I am working. Because I write, produce, direct, shoot, edit and sometimes act, I’m always working in different stages on different movies. Usually when I am working on a film, an idea will spring up for the next one. It really is what I enjoy most. I do like to travel and work on other peoples movies as well.

Keyframe: Are you simultaneously in pre-, production and post- on different films, as usual?

Verow: Things are a bit chaotic—even for me—at the moment, but it’s good. Charles Lum and I are working on the doc about The Hoist in London. I am putting the finishing touches on my next feature, Tumbledown, which will be hitting festivals this summer. I also am working on a collaborative documentary about gay public sex, The End of Cruising, with several other filmmakers. Then there’s *Required Field, a feature about an internet serial killer shot like a video diary from the killer’s point of view.

Keyframe: Your end credits often include ‘Made with available light and recycled materials whenever possible.’ You’re the eco-conscious hardcore queer experimentalist! How did this tendency develop, and do you hope to inspire fellow filmmakers to similarly reduce their carbon footprints?

Verow: The building I live in has been used for many different feature films, including my own. Whenever anyone needs a broken-down tenement they shoot in our building. One time a big movie was shooting here and they had these huge lights on all day and night. My building gets amazing sunlight. Why ruin a shoot with these huge wasteful lights? When I saw the finished film, that scene was just a minute or so and the lighting was awful. That is when I decided to go on a mission to only use available light. With new cameras you can shoot amazing images with little or no light. When I used to shoot on video, Hi8 or MiniDV I would always recycle tapes. There is so much unnecessary waste in filmmaking. I hope that I can teach other filmmakers how to just get things done, and I’m enjoying collaborating now and learning from others about different ways of thinking and doing. It’s been a fun and exciting ride for me and I want others to hop on board.