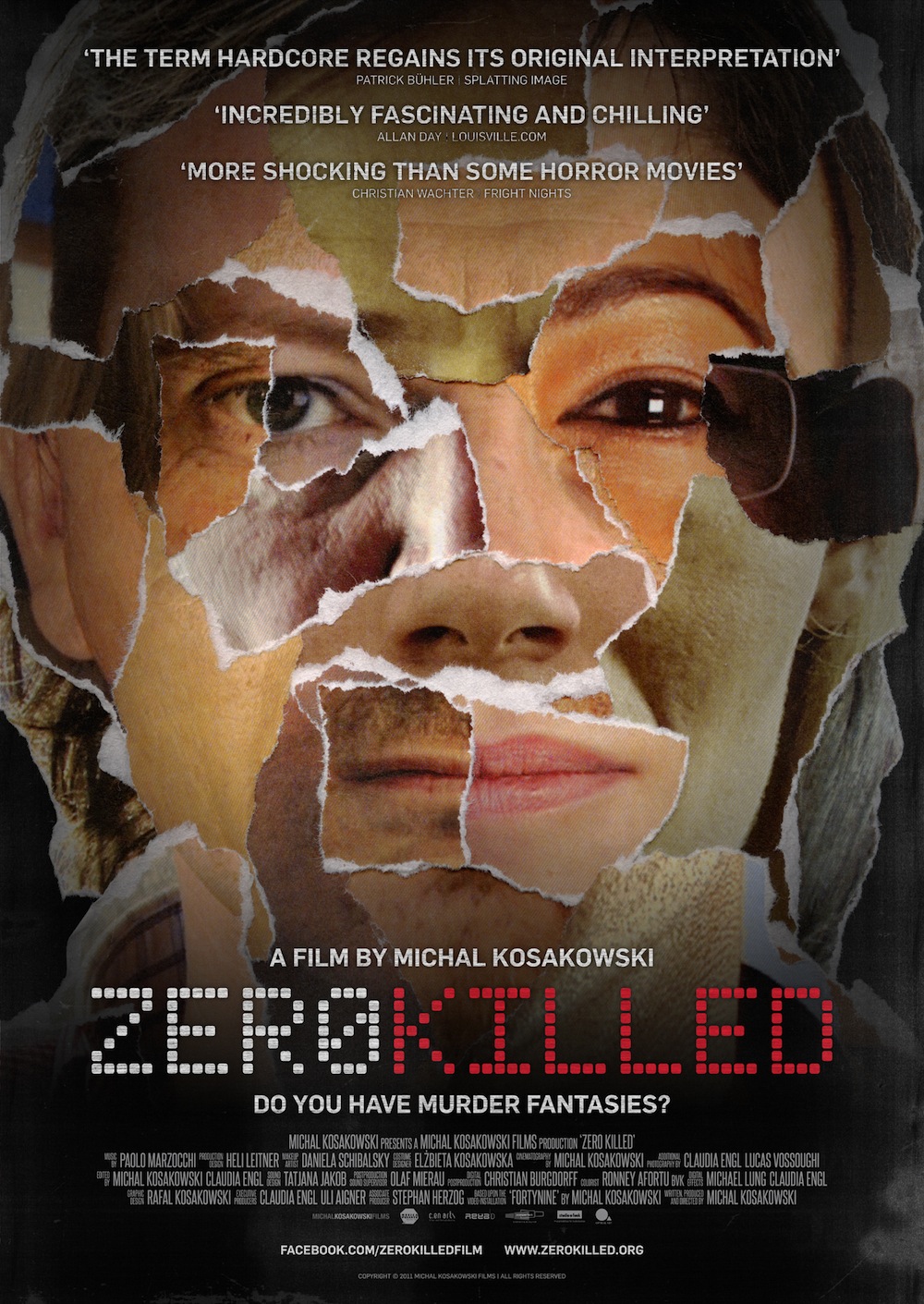

At the Chicago Underground Film Festival in 2012, an event already unique in its capacity for great programming year after year, the unconventional documentary Zero Killed made quite an impression. In the film, ordinary individuals are allowed to enact their own murder fantasies provided that they agree to appear in the resulting short. Many years later, they are interviewed about their experiences. The film passes no judgment. Nor should it. The banality of evil is in sharp focus, regardless. Fandor co-founder Jonathan Marlow spoke with filmmaker Michal Kosakowski at his home in Berlin, albeit remotely.

Jonathan Marlow: The core of Zero Killed revolves around the Fortynine project. What was the initial impetus for those shorts?

Michal Kosakowski: I was bored with the movies that I saw in Poland back in the 1970s. In 1985, I had the opportunity to come to Austria with my family. There I discovered, for the first time, a video library. That was very new to me. I started to consume many different movies. The new thing for me was that I could choose amongst many titles. This sounds kind of crazy but you have to imagine a young boy coming from a Communist country to a Western country. This was a big change. From the time that I was ten until eighteen, I watched many movies. I was experimenting with my own short movies. When I was eighteen, I realized that the ideas of normal people—of your neighbor, of people from the street—might be maybe more interesting than your own ideas. That’s how the Fortynine project started. I started collecting murder fantasies: thoughts and ideas from my neighbors, from friends and relatives. Slowly it turned into a collection of ideas. I wondered what would happen if they were to act out their own ideas, either as perpetrator or victim? I thought, in that case, they must be the best actors in the world! Because they are each portraying their own deepest fantasies. This is how it started. The first ten movies I made with friends and relatives. Then people were talking about the project and people applied. They asked me if they could be part of the project. Slowly, it grew. Ten years! It took me ten years to make all of the movies.

Marlow: From 1996 to 2007. 2007 is when you had the installation in Munich?

Kosakowski: Yes, exactly. It was actually 2006 that a curator discovered the short films. The city of Munich suddenly liked this project. I was very surprised because Munich is in the center of Bavaria. It is very, very conservative place in Germany but they believed in this project. They invest a lot of money in order to build this cube in the form it was supposed to be shown. They financed the whole project and I was able to finish the last ten movies. That’s how it happened.

Marlow: At what point did you decide that it would be interesting (for Zero Killed, specifically) to revisit the individuals from the shorts and interview them? Going back to these pieces that were shot over a ten‑year period and in different styles, it takes the whole project to a completely different place and enriches all the films in a way that otherwise would be difficult to imagine.

Kosakowski: Exactly. And it took me a long breath before I could take that step to do something else with it. The installation was very successful in Munich. I received many offers to show the Fortynine in other museums or galleries all over the world. Somehow, it always failed due to the costs involved. The transportation of this cube—6.5 tons of mirrors and metal and steel—it just became too expensive to transport the installation to another place. I got frustrated. I thought, ‘I shot so many movies and so much material and now I’m not able to show it anywhere.’ One day I thought about the idea of showing all of the short films, one-by-one, in a row. I did it! It took me three months to put… not all of them but almost thirty movies in a kind of dramaturgical order. It turned into a nice, long movie. The problem of it was that you were very exposed to the violence and suddenly you could not feel the critical point of view I had through the installation. Because in this installation, you have to understand, once you entered this mirror‑walled room full of millions of televisions, that was the criticism of all it. Because once people entered, they were scared. Not of the content but of the number of televisions! [Laughs.]

Marlow: I’ve seen the documentation of the cube. It’s very overwhelming.

Kosakowski: An [inaudible] of televisions! This was the criticism. You could stay in this room and you could watch it without being able to sit down and relax and watch violence. You could not eat, you could not sit… the world was defined by what you could do and what you were not able to do. It was an unpleasant way to watch the movies. When I suddenly saw it one-by-one, it suddenly lost its power. It just became a normal horror movie (which I never wanted to do). I said, ‘Okay. What now? What can I do?’ Then I happened to see the trailer of the movie District 9. I don’t know if you saw that.

Marlow: Yes, I’ve seen it.

Kosakowski: The trailer was built with fake interviews in-between pretending that it is real. I actually liked the idea of interviewing the people. Actually, I wanted to do just the trailer. I met two or three people from the movies. I thought, ‘What if I ask them about their memories of the shooting? Because it’s been eight or ten years.’ I started asking people these questions and, during the interviews, I found out that they are very, very interesting people. They actually started to talk about different topics. Within the process of interviewing these individuals, the idea was born to continue with the interviews and collect as much material as possible. Suddenly it turned into fifty-five or fifty-six hours of interview material with people. I had specific topics that developed through the process of interviewing. Then the idea came up, ‘What if I do a movie now?’ Which consists of, let’s say, half the time depicting the violent short films and then, the other half of the time, you have the reflective level with the interviews. Basically people showing their own violent depiction of their own fantasies and, at the same time, they’re thinking and talking about it. Basically the concept of Zero Killed was developed within the process of the interviews.

Marlow: The thing that’s interesting is that, on the surface, the premise could go very wrong. In other words, the interspersing of these short films with the interviews could actually collapse in on itself. But the editing of the film is brilliantly conceived, especially in the way that you can save the identities of these people until the end. The viewer is placed in the position of trying to imagine who these people are and then, at the end, you create a whole other layer of the banality of everything you’ve just seen by saying, ‘Okay, it’s a truck driver or a cartoonist or a radiologist.’ Basically saying, ‘These are your neighbors. These people are just like you and this is the extent of their imagination.’ It reminds me of how there is an effort to demonize murderers in the media. The reality is that that boundary line between action and inaction is usually relatively thin. These murderers are your neighbors. They are not entirely unlike you.

Kosakowski: Exactly, yes.

Marlow: The other area where the documentary could’ve gone entirely wrong—and where most filmmakers would be inclined to take it in the wrong direction—is in the use of music. Generally, makers have a tendency to want to enhance the atmosphere with a piece of music that stereotypically builds tension. Your collaboration with Paolo Marzocchi is rather brilliant. There is a contrast between the music that he’s written for the film and how it relates to the images that we’re seeing.

Kosakowski: Right.

Marlow: Can you discuss that collaboration? You have worked with him prior to Zero Killed. Was it always the intent to have a discordant relationship between what people would normally expect for a soundtrack associated with material of this sort?

Kosakowski: My relationship with Paolo is very special. He’s a crazy guy like me! He’s got his own ideas about music and he’s very successful with it. The first time I met him—six or seven years before we did the music for Zero Killed—the first piece of music I listened to was a recording of a tribal song from Africa that was recorded by Paolo and then he added this Italian ragtime piano music to it. [Laughter.] It sounded so great and these were two things that you could not imagine that they would ever match but they did. This is Paolo’s way. He’s composing classical pieces. He’s writing pieces for operas and so on. But when he works for the movies, he’s great at it because he’s got such an incredible way of producing music that is actually so against the rules. This is what I expected from Paolo for Zero Killed. I told him, ‘Come on, Paolo. Let’s do something that serves two functions.’ The music should first connect the two very different materials: the violent short films plus the level of the interviews.

Marlow: Right.

Kosakowski: It should find a way to glue them together. Then, at the same time, the second aim of the music was that he should create a third level that is something beyond the expectation of the viewer. It should create a whole other language and gives an incredible energy to the whole topic.

Marlow: While Zero Killed is your first feature‑length work, you’ve made a number of short films beyond the Fortynine shorts. Paolo Marzocchi collaborated on a number of those. Presumably, there is a different approach for how you work together which is dependent on the project?

Kosakowski: For Deep Water Horizon, I cut the movie to existing pieces of his music. He gave me access to his archive; I knew that he had many pieces that he never used or that were never published. I found many things that I really loved and put them together and added the movie to the music. That was a completely different approach than to Zero Killed. In Zero Killed, he had the finished movie and he wrote the music to it. We also collaborated on another project, Just Like the Movies. That was our most successful project.

Marlow: Just Like the Movies. I have not seen it but I’m aware of it.

Kosakowski: It is about 9/11. We basically reconstructed 9/11 with images from Hollywood movies that already existed prior to 9/11. We used excerpts from more than six-hundred movies and edited them in the way that it looks like 9/11. Paolo composed a ragtime‑based [score] to it and we performed live to the screening of the movie. It was screened in a hundred places all over the world. It screened three times in New York. It was a very successful project.

Marlow: You’re in the midst of a crowdfunding campaign for your latest project, German Angst.

Kosakowski: We actually have two crowdfunding campaigns. One, in Germany, has been successful and will end at the end of July. It’s almost done. With Nico B. [at Cult Epics] we are about to start another campaign on Kickstarter [for the U.S.] in September.

Marlow: I talked a little bit with Nico about this effort. What are the origins of the individual stories? Obviously, as an omnibus film, it’s a very different sort of project for you.

Kosakowski: Yes, true. Basically, at the world premiere of Zero Killed at the Transylvania Film Festival, I met Andreas Marschall, the director of Masks and Tears of Kali. Since then, we found out that we are neighbors here in Berlin! [Laughs.]

Marlow: Imagine that.

Kosakowski: We kind of liked each other from the first moment on. We spent a lot of time together at the festival and also after the festival. We became good friends. Andreas mentioned to me that one of his best friends is Jörg Buttgereit. Buttgereit hadn’t made a movie in twenty years. He focused more on theater and stage plays. I didn’t know Buttgereit before personally but I knew his work, of course. Buttgereit wasn’t certain if we would be able to work together. He didn’t know me. But once he watched Zero Killed and Just Like the Movies, he was fully convinced that we could work together. He realized that I’m coming from the arts scene and that I’m more of an artist than a filmmaker. He liked that. Suddenly we just had a very good atmosphere in the whole group. I offered to them that I could produce the whole movie with my company, Kosakowski Films. It just turned out to be an interesting project. We wanted to do something with its own language, something where we are not copying any existing topics. We just want to come up with something really new. Everyone has the freedom of expressing themselves in the film however they want. It’s an independent production where I am the producer and I have the right for the final cut. This is what we like about the project. Of course, with the name of Buttgereit, my name and Marschall, we have three different kinds of fan bases. At the moment in Germany, it’s all over the media. Every newspaper and every German magazine has written about German Angst. We have a lot of investors. The budget is slowly coming together.

Marlow: When would you begin shooting your segment of the film?

Kosakowski: We want to shoot the episodes in December and January.

Marlow: You would shoot in Germany, presumably, or whereabouts?

Kosakowski: We are shooting in Berlin because all three stories take place in Berlin. The city of Berlin is actually the connection to all three stories.

Marlow: Which part of the city is your part of the film set?

Kosakowski: It’s at the Spree. It’s in the Treptower Park. It’s in the eastern part, at the river in an abandoned factory. Jörg’s story is in an apartment in north Kuren and Andreas Marschall’s is going to be in Kreuzberg in a club. Do you know Berlin?

Marlow: In 1998, I lived for about three months in Kreuzberg. In essence, what you’ve described is a city symphony of a sort.

Kosakowski: Exactly. One flashback sequence that I’m producing for my episode will be shot in Warsaw. This is actually a flashback sequence to 1943, World War II, and a massacre by SS men. This is part of my episode.

Marlow: Ultimately, though German Angst is a narrative film, the subject matter doesn’t seem to be any less challenging than Zero Killed.

Kosakowski: Zero Killed had a nice festival run and, from my experience, I met people who either liked it or hated it. There wasn’t much in-between. Either they completely refused it because, perhaps, they were forced to look in their own abyss or there were people that really loved it and understood the idea. My intention was to criticize all of this violence.

Marlow: I find that to be very fascinating. People are very uncomfortable with being confronted with their own prejudices. It is often taken for granted that someone capable of committing an act of violence is distantly removed from the cultural mainstream. As a person living in the U.S., it is a surprising reaction when we’re confronted with images of violence in the media constantly. I can understand why some folks find the subject matter of Zero Killed uncomfortable. It is uncomfortable. But what you’re trying to say is exactly the thing that they’re having difficulty embracing.

Kosakowski: It’s not an easy topic. I don’t know if you’ve heard of this film, The Act of Killing?

Marlow: Actually, the catalyst for much of this conversation is The Act of Killing. Both films are mirror images of each other. Both are similar in construction. I spent last evening editing an interview with Joshua Oppenheimer and the contrast between the re‑enactments of actual events versus enactments of fantasy, I think, are quite fascinating.

Kosakowski: Yes. Yet they’re different. It’s a different approach.

Marlow: I think that your film and Joshua’s film are very interesting in their intersection of reality and fantasy. Because there is a level of fantasy in The Act of Killing that is imagining real events in a very glorified way from the perspective of the perpetrators. You’ve seen the film, I presume?

Kosakowski: No, unfortunately not. But I have read a lot about it.

Marlow: I recommend it. I think you’d like it.

Kosakowski: Actually, my working title for Zero Killed was The Act of Killing.