It started with a horse. In order to conduct his photographic experiment to prove once and for all that a racehorse’s four hooves lifted off the ground at the same time, photographer Eadweard Muybridge needed not only a way to trigger the camera shutters at the right time, but he also needed lots of light to expose the wet plates properly. Edward Ball, in his new book, The Inventor and the Tycoon, says Occident was the unlucky mammal chosen the day Muybridge gathered up all the bed sheets he could find and lined the grounds to increase the natural brightness. No horses died (valuable racehorses all) in the making of Muybridge’s images, but the billowing—and no doubt stumble-inducing—sheets terrified Occident. Ball also says that all the horses balked at Muybridge’s first shutter-trigger mechanism, silk thread stretched across the race track—they didn’t like being close-lined.

Horses, of course, have been in our motion pictures ever since. Risking life and limb, and often their dignity, they performed jaw-dropping stunts in myriad westerns, appeared merely as props, background, or color, as sidekicks to heroic lead characters, and even sometimes as the main characters. A centuries-old conveyance, worker, sport, companion and spectacle, the horse was still integral to daily life at the time cinema was invented, not yet completely usurped by the mechanical. The Lumières filmed many horses on their worldwide voyages with their hand-cranked cameras, including horse-drawn buggies in the background at New York’s Union Square (New York: Broadway at Union Square) and some shirtless dragoons riding bareback across a river in eastern France (Dragoons Crossing the Saône, 1896).

Produced by Thomas Edison—who had rebuffed Muybridge’s attempts to collaborate—1894’s Bucking Broncho showed real-life cowboy Lee Martin of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show riding Sunfish in a corral built especially outside the glass studio, the Black Maria being too small for such a production. According to early western scholar Scott Simmon, the man standing on the fence repeatedly firing his gun into the tightly framed corral is another authentic cowboy, Frank Hammit, originally chosen to perform for Edison’s camera with his own horse El Dorado but “deemed it not advisable … as the place was not large enough, the animal being an extraordinarily dangerous one.”

Horses and cowboys left idle by the vanishing West soon found work in the western, with its increasingly thrilling thrills. A Jewish man from Arkansas lied to Edwin S. Porter about his horsemanship to get cast in The Great Train Robbery and the cowboy star (Broncho Billy Anderson) and the stunt rider were born. Stunt doubles also became common for horses, with the photogenic and valued specimens preserved for interacting with humans and unfortunate rental horses used for dangerous stunts. Attitudes about the animal, its use and care, were holdovers from the Imperial Era, when according to John Berger, “The capturing of the animals was a symbolic representation of the conquest of all distant and exotic lands.”

The horse became a character in Pathé’s 1907 short Le cheval emballe, or The Runaway Horse, in which a trick shot shows the horse running backwards. William S. Hart, an experienced horseman who spent part of his childhood in the Dakotas, found a small red-and-white pinto at Inceville, Fritz, and together they formed a successful duo that was duplicated many times over in the future of movies: a cowboy and his trusted steed. In her book, Hollywood Hoofbeats, Petrine Mitchum says that Fritz’s unique markings meant it could not be doubled, but it was well trained to fall on cue at a time when many horses were tripped to achieve the desire effect. (The malevolent Running W rig has cuffs that are strapped to a horses hooves, which are then connected to a stake buried deep in the ground.) Hart, who loved Fritz (marking the horse’s grave with the words “A Loyal Comrade” and eulogizing it in the prologue of his own last film, 1938’s Tumbleweeds) never risked its hide for stunts. But the moving picture hero was not above withholding Fritz from films for two years in order to get a raise.

Absent from 15 of Hart’s movies, Fritz finally returns in 1920’s Sand, whose plot is built around the joyful reuniting of horse and rider who then must chase down a thief, dropping straight off the edge of a cliff in the process. According to Mitchum’s book, this stunt was performed in Fritz’s final film, Singer Jim McKee. She goes on to say that a concerned Will Hays, head of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association, questioned Hart about it. When Hart explained that the horse was actually a dummy replica, Hays approved the film. After the film’s release, concerned fans still wrote letters asking after Fritz. Looking again at the drop in Sand, it unfolds exactly as Mitchum describes for the McKee stunt and it’s obvious the “horse” is a prop.

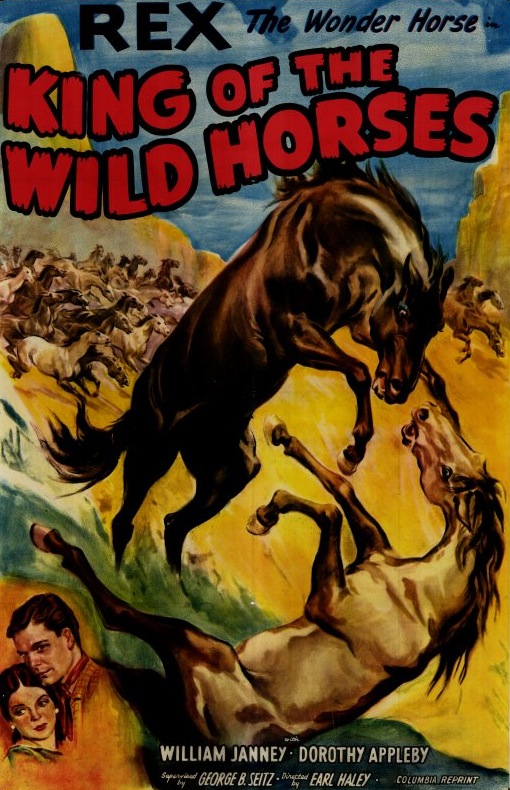

A rescue from a detention center in Colorado, Rex was a powerful black stallion with undeniable onscreen charisma. He had been branded a killer because a young runaway died inexplicably after stealing the horse for his getaway. Discovered by producer Hal Roach’s animal wranglers and billed as “the Wonder Horse,” Rex was the star of its own movies, beginning with The King of the Wild Horses (1924) for which it makes a spectacular leap across a ravine [23:12] and later off a cliff into white water. Doubles stood-in for Rex, not on stunts but for close shots with human actors, as the unpredictable animal often reacted badly to them. The horse makes quite a vision leaping off that cliff, and without any apparent provocation. Mitchum also says that Rex was a bit of a diva, refusing to work when tired and, even once, taking off during a shoot, getting as far as 17 miles away. If that was Rex, and not a stunt double, leaping into the river, the break was well deserved. Watch the entire amazing sequence below.

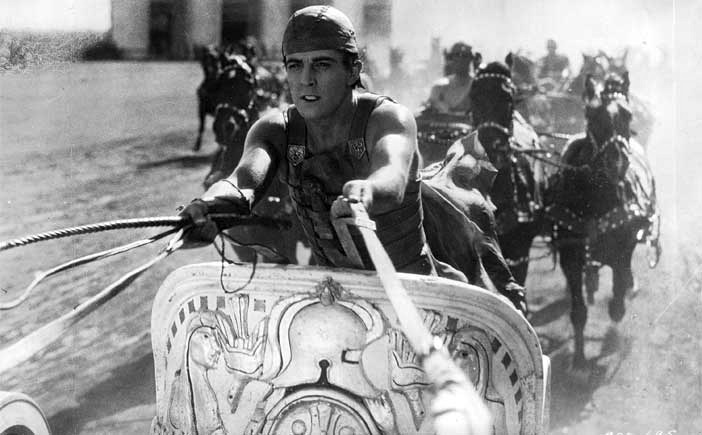

Plagued by budget overages as well as quarreling directors and writers, Ben-Hur (1925) goes down in history as the most deadly film (American, anyway) for horses. Second unit director B. Reeves Eason, a veteran of westerns and the use of the Running W, shot the chariot race, which claimed the lives of as many as 150 horses (reports vary widely). He reportedly offered a $5,000 cash prize so stunt riders would give their all to the race. The big-budget and the big canvass required a stunning racing scene, and despite danger to performing animals, it became the standard by which all others were judged. It took about 15 more years and many more dead horses for some oversight to be established.

Americans weren’t the only ones risking the lives of their equine actors. Sergei Eisenstein, tasked with communicating to a overwhelmingly agrarian popular, often used animals in his films. In Strike, he compared police agents to less agreeable qualities of certain beasts (monkey, fox, etc.), and the final dramatic sequence of his first feature intercuts the brutal repression of the strike with the graphic butchering of a bull. The General Line, about the benefits of Soviet collectivization, was later edited to suit Stalin’s tastes and renamed Old and New. His last silent picture, it not only features animals working the farm (some seem quite distressed: the chubby pigs end up dead) but also in service of Eisenstein’s characteristic “intellectual” montage. A sped-up loop of bleating, drooling sheep is intercut with villagers repeating the sign of the cross as they pray for rain.

The most memorable sequence in October, a feature made to celebrate the ten-year anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, consists of a beautiful white horse skittering through St. Petersburg’s rebellion-wracked streets. A sacrifice in service of Eisenstein’s esoteric symbolism, it is apparently killed offscreen and then reappears as deadweight hanging off the Palace Bridge. Eisenstein described the task of having to kill the steed as only one of many pressing things he needed to do that day. “We only had twenty minutes a day. And in those twenty minutes we had to kill a white horse, as it galloped madly pulling a cab; let drop a golden-haired girl, let the two halves of the bridge open up, let the golden hair stretch across the bottomless abyss, let the dead horse and the cab swing from the raised edge of the bridge, let the cab fall… On screen is takes a lot less than twenty minutes. But to film it takes hours!” With 20 million starving peasants, it was probably hard to get worked up about a few dead animals.

The risks continue, and not just for horses, who also were subjected to the Tilt Chute, shock collars and pellet guns. Thomas Edison electrocuted an elephant on camera to prove his electrical current was superior to a competitor’s. Percy Smith glued a fly’s wings for 1908’s The Acrobatic Fly. Puppet animation pioneer Ladislas Starewicz used beetles (and other dead animals) to such realistic effect in for The Cameraman’s Revenge, one London newspaper wanted to know how he trained them so well. Lions were beset by wire mesh floors charged with electricity and alligators had their jaws bound with wire. Just being on a movie set can be hazardous. The well-treated Strongheart (silent German Shepard star who predates Rin Tin Tin) got accidentally burned on a set light and later died from the wound that grew cancerous.

Objections have been voiced about animal abuse in filmmaking since its beginnings. One Briton wrote about a 1897 Lumière exhibition, “A Spanish bullfight with a remarkably fine bull, is also depicted; and, as Mr. Maskelyne, who acts as explainer remarks, ‘makes us sorry for the animals, and for those who can enjoy such a spectacle.’” In 1933, shortly after taking power, the Nazis passed an animal protection act that prohibited the use of animals in entertainment, “to the extent that these events cause the animal appreciable pain or appreciable damage to health.”

The very power of these images, however, are what fired the movement to create safer ways to film animals. A 1914 propaganda short about how London dealt with decrepit horse traffic depicted the “disposal method:” driving a knife through the horse’s heart and letting it bleed out. The London Times wrote, “… these pictures cannot be shown in public, however vividly they prove the need for some improvements of existing conditions.” The still image of the single horse falling off a cliff to its death in the 1939 film Jesse James was used to galvanize support for the American Humane Society’s supervision of animal actors.

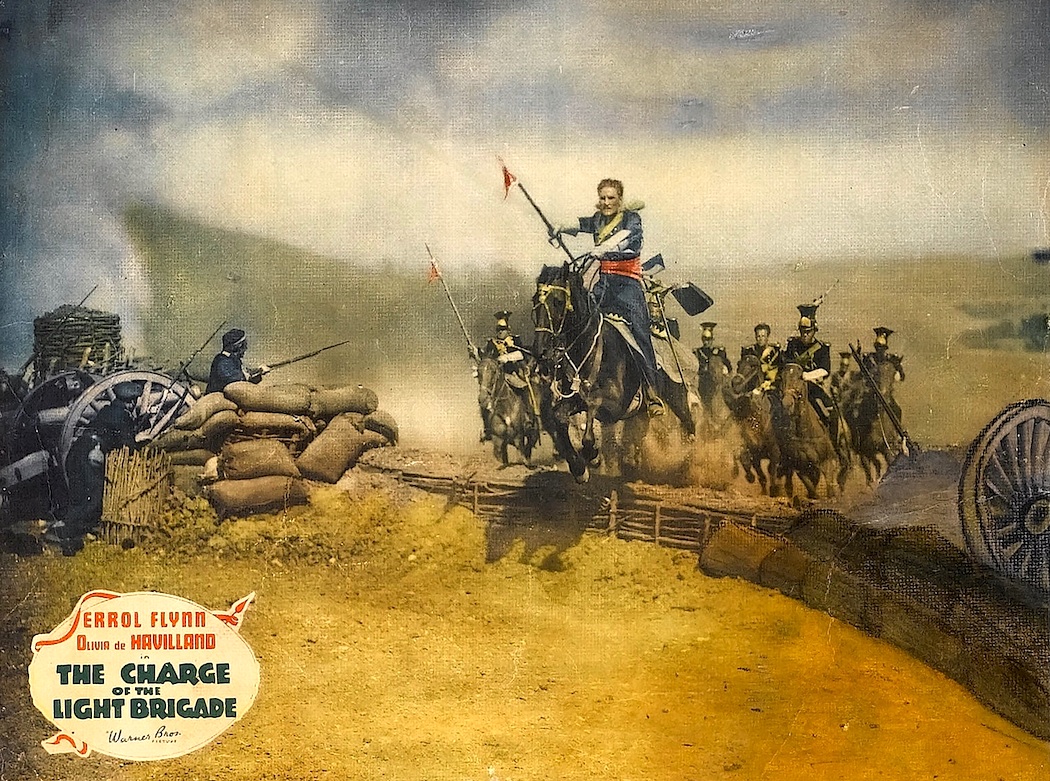

A badly performed stunt can certainly take away enjoyment of a film but knowing the animal you are watching is dying for the film is worse. (Warner Bros. didn’t re-release its wildly popular 1936 film The Charge of the Light Brigade, for which the Running W was once again used, killing an estimated 25 horses.) But if you want to be as sure as you can that a horse on screen wasn’t tripped (Yes, they still trip horses), you can tell by the way they fall: on their sides, usually to the left and always with their heads away from the ground. When they are tripped, they make a spectacular somersault, which mostly likely breaks their legs. It might be cinematic but it shouldn’t be entertainment.