This year, Fandor’s Keyframe produced forty-six video essays, a figure on par with last year’s output. Beyond the sheer number of pieces produced on a near-weekly basis, a greater number of contributors figured in the mix. Ignatiy Vishnevetsky crafted a poetically attentive tribute to critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, and Jorge Gonzalez Ortiz produced an elegant overview of Gravity director Alfonso Cuarón’s cinematic motifs. In an interesting self-reflexive move, Ehsan Khoshbakht filmed video interviews with essay documentary filmmakers Mark Cousins, David Cairns and Paul Duane. And Nelson Carvajal made “Chicago Underground, Unleashed,” “Women of the Avant-Garde” (featuring fascinating use of horizontal split-screen banding) and “Evidence of an Elliptical Film,” which recasts the earliest films of cinema history as a hotbed of creative energy that bears a curious resemblance to today’s online video scene.

As for myself, I chipped in thirty-nine videos (not counting my assistance in the Rosenbaum tribute), which is a lot considering that this was the year that I gave up on film criticism as a viable profession. To get into the reasons would take us too far away from the purpose of this recap, but suffice it to say it had something to do with money: not simply because there’s no money in being a film critic, but also because of how the money motive affects the quality and character of film criticism. The moment I lost hope in being able to sustain my living as a critic turned out to be a moment of liberation from the desperate routine of zeitgeist chasing, story pitching and social media chiming that freelance film writers find themselves locked into whether they enjoy it or not. I now realize that these prevailing practices have bogged film criticism in a set of conventions, stylistically and worse, ideologically. These automated ways of writing and thinking that prevent the practice from realizing its full potential at a point in time when it has more resources to do so.

All of this has everything to do with my thoughts on the video essay and its role in the current landscape of film culture. When people like me, Matt Zoller Seitz, Catherine Grant, Christian Keathley and others first started making video essays a few years ago, there was a genuine sense of excitement that we could finally use the movies to speak about this art form instead of relying on just words. This work could give criticism a new sense of vividness and interaction with regard to its subject. At last, cinema and criticism could actually merge in ways it hadn’t before, with the potential to transform both.

Since that initial enthusiasm, there has been an explosion of activity with many impressive works by a long roster of creators. But curiously, all of this output (including my own) has left me unsatisfied and more than a little wary. One reason is that for every exciting and innovative video that gets produced, there are many others that show just how conventional and formulaic the video essay has become. One key example of the onslaught of the ersatz is the YouTube Channel WatchMojo.com, which has turned the video essay format into a salt mine for easily consumable online content in its most evil incarnation: the top ten list. It’s symptomatic of the lizard-brain tendencies of online content consumption that this zombie-like instant click bait gets more traffic than a thoroughly-researched or highly critical thinkpiece.

But there’s a more profoundly disturbing realization to be made if one looks at the subject matter addressed in these zombie videos—The Simpsons, Stanley Kubrick, Hollywood movies, all familiar pillars of pop culture—and realizes that even the more thoughtful and complex video essays by recognized and respected practitioners also trade in this currency. I’m certainly no exception—the two most popular videos I ever made deal with Steven Spielberg and Paul Thomas Anderson respectively. The fact is that most of these efforts exist within a prevailing culture of what I call “fanboyism:” an unmitigated, cult-like enthusiasm for a prevailing set of cultural products. This fetishistic attachment is certainly not limited to pop culture—fanboys and fangirls can be found in all types of cultural circuits, from arthouse festivals to experimental enclaves; after all, cultural circuits rely on them to thrive and proliferate. It’s all part of a market industry of enthusiasms that values and circulates our passions.

All of this is to wonder just how much video essays have really done to change our appreciation of cinema, at least in terms of changing what we care about and how we care about them. Have video essays really done anything to transform our relationship to films and to pop culture, or are they just a slick new filter to attach to our pre-existing lens of enjoyment, a new way to lock us deeper within our consumption of commercial goods? Is this really “criticism,” or a heightened version of fanboyism? Increasingly I wonder if a distinction can made between fanboyism and a less enamored, more critical mode of engagement, one that stands autonomously from its subject rather than beholden to it. What would such autonomy look like, and what would it do to our current cultural dynamic that trades in cult fetishes of beloved cultural objects?

Many of these thoughts are informed by my experiences this year after giving up on professional film criticism and searching elsewhere to find a new relationship to cinema, for new ways to look and to think. Several of the videos I made this year reflect these experiences and a growing awareness of what it is exactly that I am seeking: how to turn viewing into an act of autonomy rather than automatism. The five most telling instances of this journey are embedded below, with some comments. The other thirty-four videos I made are listed further below and are grouped by categories; those in bold are the ones I consider particularly successful in trying something new, or at least hinting at new ways of looking that might be better uncovered in the future.

Key Instances (click on titles for original context)

How Carl Dreyer Created a ‘Cinematic Uncanny’

This video sprung from a seminar I attended, “The Uncanny in Cinema,” taught by the legendary film scholar Tom Gunning at the University of Chicago. Gunning led the class in a fearless exploration into the numerous shadowy areas within cinema, and how it places us in a paradoxical state of being and not-being with what in some respects are essentially projections of phantoms. I came away with a more philosophical regard for cinema as a powerful experience of disorientation, and a greater degree of attentiveness and comfort in detecting its mysteries, confronting its displeasures, and learning how to stand simultaneously inside and outside of its aura.

[iframe width=”420″ height=”315″ src=”//www.youtube.com/embed/b2ub9_wkYpc” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen]

The Flaherty Seminar was the most galvanizing week of the year for me, bringing me to the point when I began to grasp the stakes and possibilities of a truly active participation with cinema and the need to be fearless in pursuing that potential. For anyone looking to challenge their preconceptions and relationship with film and filmmaking, I highly recommend attending.

[iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”//www.youtube.com/embed/cGUmPCzBQxI” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen]

Every Fight in Wong Kar-wai’s THE GRANDMASTER, Ranked

My way of dealing with the plague of list-making that has infested film criticism and internet culture. I’d like to think that I performed a rhetorical kung fu move on that readymade formula by smuggling an aesthetic argument amidst the banal number rankings. Who knows? I should also acknowledge that I was totally wrong about this film being Wong Kar-wai‘s first foray into digital filmmaking. And the fact that I was mistaken opens up a line of ontological inquiry: what does it mean to no longer be able to tell the difference between film and digital, when a film’s look has been so thoroughly processed that it no longer resembles “film” as it was once known? These are the questions that interest me now. I may have to come up with a list video, “Ten Movies that Blur the Line between Film and Digital,” to explore further.

[iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”//www.youtube.com/embed/YKAWUGH_qhs” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen]

What Radical Filmmaking Really Looks Like

A video that helped to bring me to a near-total state of alienation from the current cinema, as I realized just how timid it is compared to what has been done before. How many films and filmmakers these days really try to change the world, much less believe that films have the power to do so? These are uncomfortable thoughts that threaten to make one hate a whole swath of movies; but one thing I learned this year was that learning how to truly love the movies involves understanding what it means to truly hate them: how much potential they have, and how much of that potential has gone unfulfilled. Having made the video, I also recognize the danger of falling into a fanboy endearment towards these films, a cozy admiration that renders their radical power neutered unless one truly internalizes their example. Until that happens, they can only hang over us like the avenging angels of our conscience.

[iframe width=”420″ height=”315″ src=”//www.youtube.com/embed/7bvzzdAzXJs” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen]

Being back at school has put me in a more playful environment, as seen in this video that was partly shot on school premises (that’s tuition dollars at work). This video approaches a more “essayistic” turn, in that classic Montaigne sense of “essaying” a discursive series of thoughts rather than laying out a clean, didactic argument as I’ve typically done. In that regard, it’s the closest I’ve come to realizing this autonomous relationship with the movie I have in mind: one that’s engaged but not endeared, always questioning, and using questions to spring into action.

[iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”//www.youtube.com/embed/ophBrz6D9kI” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen]

The Rest:

Genres

What Does China’s Greatest Film Sound Like?

Four Ways of Looking at Chinese Reality

Experimental Fireworks in the Land of Free Radicals

People

Jem Cohen’s Ground-Level Artistry

Laura Poitras, Lives on the Line

Keith Uhlich’s Cinema Breakdown

Actors

Bruce Lee, Before and After the Dragon

The Soundless Fury of Kate Lyn Sheil

Young Judi Dench Shines at FOUR IN THE MORNING

Recuts – New Ways of Looking

New Year’s Irresolutions and a Cinematic Cliff | Richard Linklater’s SLACKER

The Gospel Faces of Pier Paolo Pasolini

Steadicam Money Shots in RIVERS AND TIDES

Tracing THE BLACK BALLOON in Google Maps

39 Ways of Looking at Her Beauty

The Glitch Games of COMPUTER CHESS

How to Have a Radical Documentary Holiday Party

Single Film Essays

Between the Lines in THE DAY HE ARRIVES

Festival Reportage

Best of the 2013 Chicago International Film Festival

Who Should Win the Oscars 2013

Who Should Win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress?

Who Should Win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor?

Who Should Win the Oscar for Best Lead Actor?

Who Should Win the Oscar for Best Lead Actress?

Why SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK Should Win Best Picture

What Does Oscar-Winning Cinematography Look Like?

Announcing the Oscar Winners… of 1922

Summation

Lessons Learned from 2013′s Films

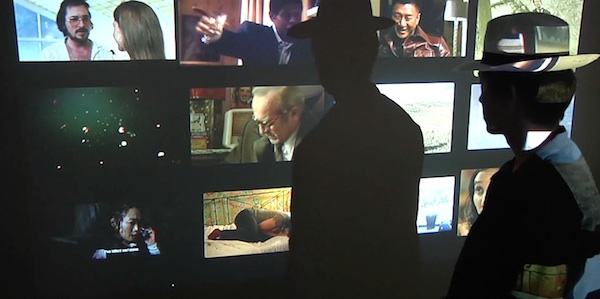

The Best Films of 2013, All on One Screen

Kevin B. Lee is a filmmaker, critic, video essayist, and founding editor of Keyframe. He tweets as @alsolikelife.