Narrowing down the “Best Shots of 2013” is a little like trying to remember the specifics of a fading dream. While researching these images again, sometimes months removed from initial viewing, many of these shots seemed different, defined by compositions, angles and colors that did not match my own memory. Even so, what remained was their essence, the power they hold in forming their respective films’ collective shapes. In each case, these magnificent shots manage to encapsulate their films’ key themes and subtexts in a singular moment.

With this particular list I tried to embrace the dynamism of 2013’s best films, both from America and abroad, mainstream and art house. It’s a strange group, probably because they are very personal to me, a collage of what this year in movies meant and continues to mean. Hopefully it’s a collection of compositions and shots that will inspire you to take a look at the films themselves in question, be it for the first time or for a second, more inquisitive glance.

1. ‘Look Away’ (The Lone Ranger)

For nearly two hours, Gore Verbinski’s massive and subversive Western burrows its indictment of the Native American genocide under images of dark violence, cartoonish action and physical comedy. But it’s a quiet shot near the end of the film that sums up perfectly how historical trauma can transcend artifice and send ripples through time, affecting new generations in profound ways. The aged Tonto (Johnny Depp) turns away from a young child dressed as the titular cowboy hero and stares off into the distance of a fabricated Monument Valley. Up to this point, the diorama set design has been a source of plastic inspiration for the character’s narrative recitation. But here, the crippling sense of physical and spiritual imprisonment inside Tonto’s heart is given a physical revelation. He refuses to empower the kind of myth-making and archetypes that have nearly crushed his will, and this final disavowal is an amazing act of protest against a genre (and Hollywood ideology) that has long used the suffering of many as a source of entertainment.

2. ‘Ice Cream’ (Manakamana)

Made up of eleven-minute shots documenting the ascent and descent of various pilgrims visiting the legendary mountain temple in Nepal, Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez’s hypnotic film asks the viewer to actively observe the nuances in a given frame. Two men perform a wonderful impromptu musical performance, a horde of goats becomes entangled, and three young teens discuss the tree lines. But in a non-“fiction” film that favors performances of many kinds, my favorite is when two women spend their trip down from Manakamana messily eating ice cream. The extreme heat makes this a precipitous (and hilarious) slapstick event, one that celebrates the improvisation of a seemingly small moment that can avalanche into something whimsical and human.

3. ‘Feline Reflection’ (Inside Llewyn Davis)

Joel and Ethan Coen’s melancholy vision of artistic failure is all about the heartache of watching the world pass you by. Oscar Isaac’s struggling folk singer embodies this notion throughout, often looking at the evolving world and its occupants only to find disappointment instead of inspiration. The same cannot be said of the gloriously inquisitive ginger tomcat Llewyn is forced to carry across town on the subway. Watching through the window as the train careens forward, the cat’s reflection captures a sublime sense of discovery that is both surprising and resonant.

4. ‘Dead Men Walking’ (In the Fog)

The opening tracking shot of Sergei Loznitsa’s harrowing war film follows a column of German soldiers as they lead a trio of prisoners to the hangman’s noose. Beginning with the frame positioned as a bystander looking off into the countryside, the camera then jumps into formation behind the walking dead. The long take continues as they move through a Nazi occupied village, its denizens looking on in shock as they realize what’s coming next. The shot becomes even more powerful when the frame opens up to reveal the sheer depth of Loznitsa’s mise-en-scène, which expands to include multiple planes of bustling activity in a place dominated by fear.

5. ‘Ass-cam’ (Passion)

An early highlight of Brian De Palma’s sleek and technologically perverse thriller, the scene where Noomi Raplace’s advertising executive places a cell phone in her assistant’s back pocket and begins recording is pure cinema. There’s a single frame early in this sequence that stands out as especially warped. It’s the first moment captured by the infamous “Ass-cam,” and it’s as divisive and contorted as anything De Palma has ever composed. Both character’s faces express excitement, but the way their bodies are spliced and repeated through the various levels of reflection damns their joy from the beginning.

6. ‘Bird’s-Eye View’ (Drug War)

For an action film so attuned to the close proximity of gunfire, shattering glass, and perforated skin, Johnnie To’s relentless masterpiece also contains a feeling of solemnity. It’s entire story is one breathtaking set-piece after the next, culminating a sprawling gunfight on a deserted urban street. To then cut to a bird’s eye view shot of the faceless bodies lying in pools of blood and by wrecked vehicles. Like a flock of birds breaking formation, a tactical police squad splits up into two groups surrounding the crime scene. The quiet solitude inherent to this image gives Drug War its tragic finality.

7. ‘Morning Light’ (Norte, the End of History)

A window opening inspires a long take during the second half of Lav Diaz’s enigmatic film about moral decay and psychological crisis. The camera is placed outside of the riverside abode of a family struggling to overcome their patriarch’s imprisonment. Three soldiers walk by noticing the woman looking out onto a brilliant purple morning horizon where a fire rages is the far distance. The sound of a rooster gives way to a wave of crickets and birds off in the distance, the camera gliding right, then back left as a motorbike drives into frame and back around to the front of the house. The family unloads groceries and goes about their morning routine. Here, the mundane becomes epic.

8. ‘Performance’ (I Used to Be Darker)

Matthew Porterfield’s third feature stands out for its tender but frank examination of a family slowly and gracefully splintering apart. Like Inside Llewyn Davis, it’s also a film that deals with an artist stunted by the limits he puts on himself. That man is Bill (Ned Oldham), a good father and one time musician who has given up his passion for songwriting in order to make a living for his family. Up to a certain point, Bill’s process as a musician is somewhat obscured, that is until Porterfield’s static camera films him playing a wrenching folk ballad in his basement. The beauty of this long take is suddenly dashed when Bill slams his acoustic guitar into a cement pillar multiple times, shattering both the physical and emotional possibilities of such a lovely moment.

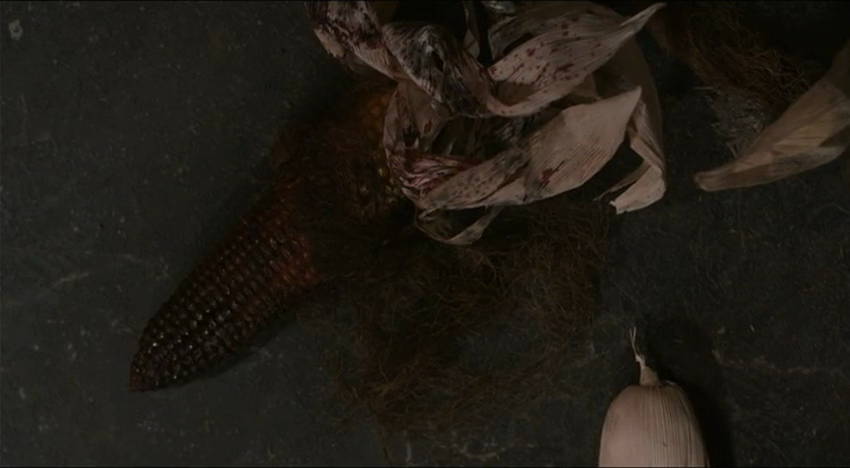

9. ‘Corn husks’ (Bastards)

Without ruining exactly what the darkened and bloodied corn husks represent in Claire Denis’ nasty neo-noir, let me just say that once its context is revealed this blistering image will haunt your soul until the end of time.

10. ‘Freedom’ (This is Martin Bonner)

Upon being released from a Nevada penitentiary after serving twelve years for manslaughter, Travis Holloway (Richmond Arquette) stands on the street outside his cheap motel room and takes in his newfound freedom. But this is not a joyous occasion in Chad Hartigan’s This is Martin Bonner; instead, the filmmaker gives us a slow 360-degree shot that begins on Travis’s weathered face and then pans across the Reno skyline before ending where it started. The eerie silence solidifies the openness as something disquieting and potentially suffocating. Prison cells come in all shapes and sizes.

For the complete list of year-end lists on Keyframe, go to The Year in Film: 2013.

For the complete index of the films on these lists, go to 2013 Year in Review: Indexed.