Last year a poll found that twelve percent of Americans admitted to watching porn online, a statistic that even staid Time Magazine found laughable, chalking the low number up to “bashful” respondents. One suspects the actual portion of folks who at least occasionally peruse the “adult” side of those interwebs is considerably higher. And regardless, nearly ninety percent of American households have some kind of computer, meaning that we are a nation whose overwhelming majority is seldom more than a few clicks away from free XXX content, 24/7.

It’s enough to make you yearn for those more “innocent” days of yore, when in order to experience cinematic sleaze you actually had to leave the house and pay cash money. You’d either slink to that cordoned-off section of the video store or (before the advent of home video) go to a permanently underlit movie house on the sketchy side of town, in both cases hoping not to be seen by neighbors or coworkers. And before THOSE were options…well, not so long ago, a man had to go pretty far out of his way to access even a flash of filmed partial nudity. (Forget about smut directed toward female consumers, as that concept scarcely existed before the 1970s.)

Yes, before it became legal to photograph and exhibit people actually performing the act of love (even if it was now more an act of commerce), there was a good half-century in which generally much, much less graphic titillation was enjoyed by “discerning viewers” in variably more furtive circumstances. The celluloid evidence may look awfully quaint to us now, but it was the hottest thing going for decades in which any “Sexual Revolution” seemed impossibly far off. It’s a saga amply detailed in Frank Henenlotter’s That’s Sexploitation!, the documentary that tells you everything you wanted to know and more about such largely forgotten phenomena as “nudie cuties” and “smokers.”

Henenlotter is well-qualified to be our tour guide through these halls of vintage naughtiness, as someone who grew up watching exploitation trash in the long-gone grindhouse mecca that once lined Manhattan’s 42nd St. (The area now better known as Walt Disney Presents Broadway.) He won the adoration of genre fans creating his own schlock-horror classics in Basket Case and Brain Damage, then managed to push the envelope further with the gleefully tasteless sex/gore constructs of 1990’s Frankenhooker and (after a long layoff) 2008’s Bad Biology. He’s also long been affiliated with Something Weird Video, probably the world’s premier distributor (and preservationist) of obscure exploitation cinema, even curating his own line of ultra-rare titles under the imprint “Frank Henenlotter’s Sexy Shockers.” (Thanks to which you can enjoy such dusty jewels as The Curious Dr. Humpp, Honeymoon of Horror and Three on a Waterbed in the comfort of your own home.)

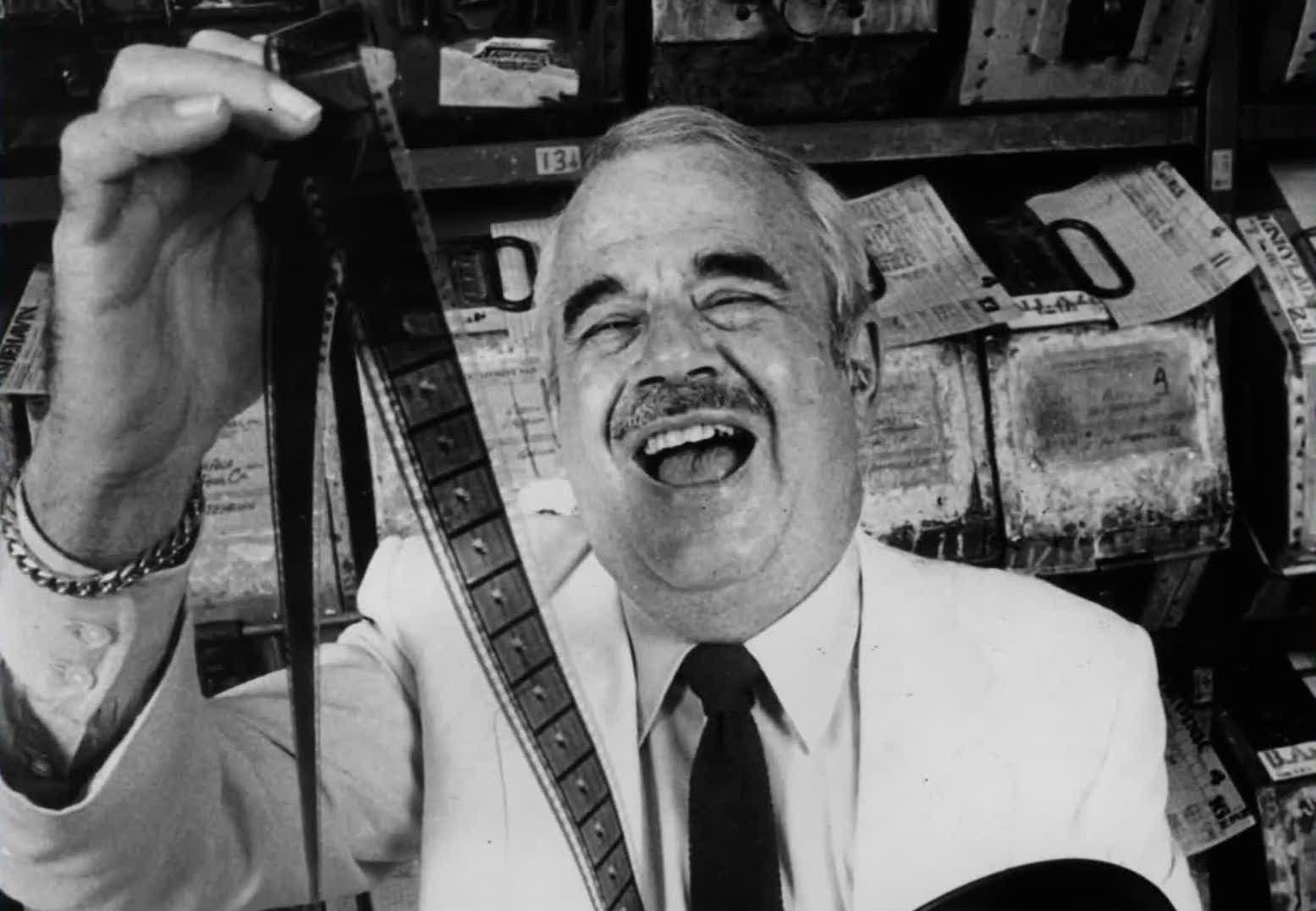

But Henenlotter mostly turns over the narrating duties here to an even greater authority in such matters, fabled exploitation producer David F. Friedman. The latter is interviewed in his rural Alabama home, a virtual museum of grade-Z movie memorabilia; notably frail here, he died shortly afterward (in 2011 at age 87), and the documentary is dedicated to his memory.

The two men chronicle a history of sexploitation that is almost unimaginable as anything but a Something Weird production, its in-house status allowing access to the mother lode of retro erotic clips. They commence in the 1920s, when “stag films” first began surfacing regularly for exhibition in brothels (where they were also often shot), men-only clubs and other strictly private venues. While some (the aforementioned “smokers”) had hardcore content, many like 1929’s Why Girls Walk Home or 1938’s Uncle Si and the Sirens simply offered playful female nudity.

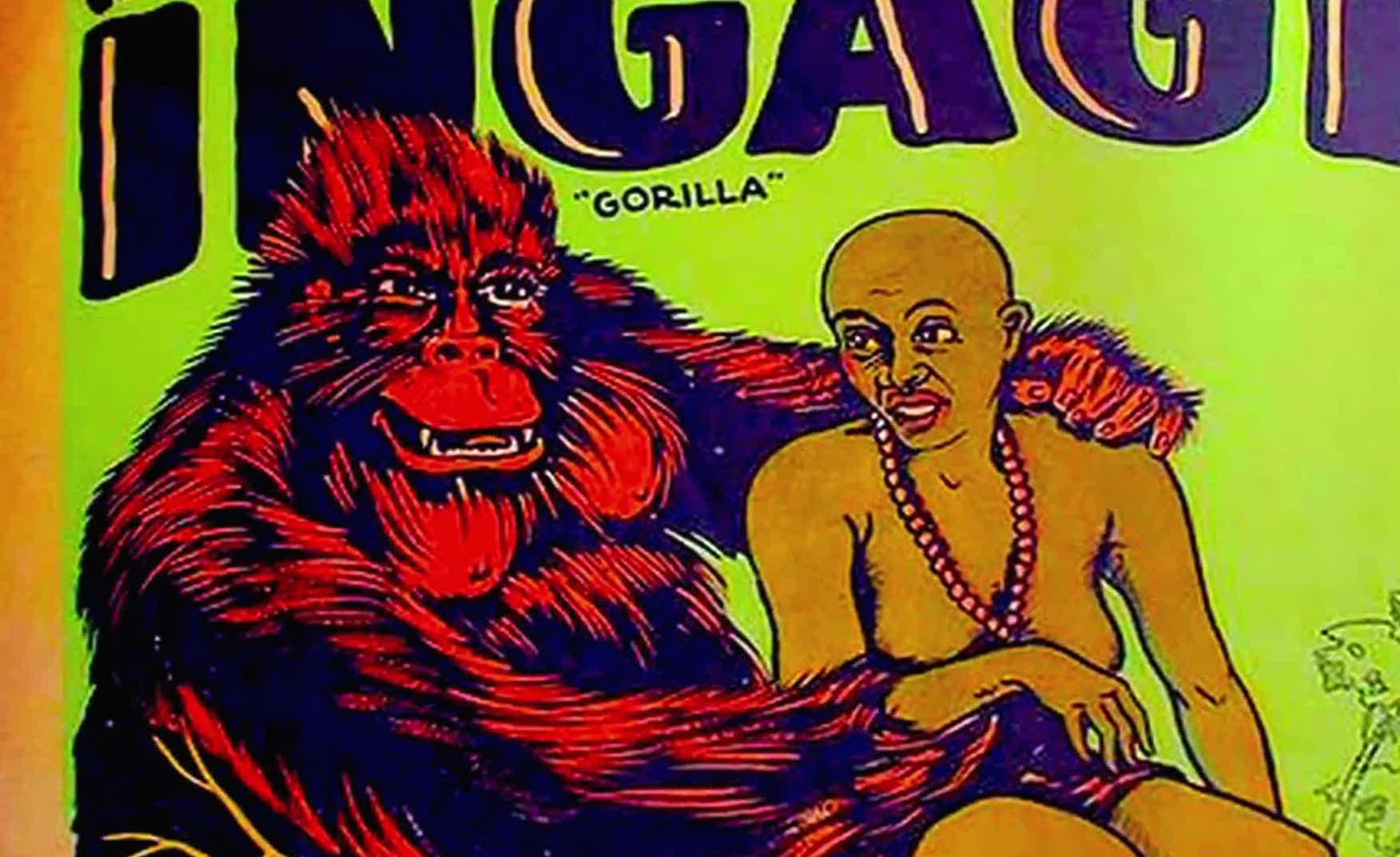

When the censorious Production Code began being enforced in 1934, the milder but still provocative sexual humor and suggestiveness Hollywood had offered in the 1920s and the “pre-Code” talkie era ground to a halt. Seizing their opportunity, exploitation producers began making low-budget “cautionary” features like Wages of Sin and Gambling with Souls that were invariably heavier on the sin depiction than they were on the corrective moral instruction. These movies (Reefer Madness being the most famous) were often shot in both “hot” and “cool” versions, varying the degree of naked flesh shown to suit differing state laws on obscenity. Another genre that skirted legality was what Friedman dubs “goona-goona movies,” ersatz jungle adventures that managed to get away with female toplessness under the guise of “anthropological” interest. (Never mind that the jungle maidens were often white chicks in dusky makeup, or that their frequent amorous abduction by actors in ape suits bore no resemblance to reality whatsoever.)

After World War II, showmen like Kroger Babb flourished well off the mainstream film industry grid by touring town-to-town such alleged “sex hygiene films” as Mom and Dad, which offered racy content under the guise of educational intent. No such pretense sobered the sexiness of “specialty loops” offered at arcade “peep shows,” where you inserted a coin into the machine to see each successive section. (“Part Four has ended—can you survive? Drop a dime to see Part Five!” read one greedy intertitle.) These spicy miniatures often featured burlesque queens doing their novelty strip acts.

While European films (notably those starring bombshell Brigitte Bardot) began allowing relatively frank sexuality in the 1950s, American movies were still way behind. They got a break when courts determined that nudity, in itself, was not obscene. That ruling unleashed a flood of utlracheap “nudist camp” films (Around the World with Nothing On, Doris Wishman’s delirious Nude on the Moon) in which nature lovers were forever seen playing volleyball with their backs to the camera, or with conveniently located shrubbery covering their netherparts. Likewise, the “nudie cutie” films pioneered by Russ Meyer’s 1959 The Immoral Mr. Teas offered lots of bare-breasted women but no other sexual content in silly comedies that Friedman dubs “the stupidest films on the face of the Earth.”

As the first heat waves of the Sexual Revolution hit, however, things began changing quickly. Where before there had been one or two hundred theaters nationwide showing such “adults only” artistic endeavors as Goldilocks and the Three Bares, suddenly their number skyrocketed as censorship barriers tumbled one by one. Friedman fondly recalls the “Swinging” Sixties as his favorite decade, when exploitation was “set to a go-go beat,” and his own career was at its peak. There were “counterculture” cash-ins like The Acid Eaters; “roughies” like Olga’s House of Shame, taking advantage of the “new permissiveness” regarding both sex and violence; et al. When the MPAA instituted the G-to-X ratings system in 1968, it seemed to many that now the floodgates had opened and the screen would be flooded with filth.

It took a few more years and court battles, however, before actual “hardcore” sexual depictions could be projected onto American screens without fear of prosecution. By the time the last legal hurdles were cleared, porn flicks had already killed off much of the market for softcore “sinema.” “The movies became explicit, and the fun stopped,” Friedman laments.

That’s Sexploitation! draws the curtain on its subject at this early 1970s juncture. Drive-ins and grindhouses were then already on their way out, soon to be buried by home video. Cable TV would pick up a bit of the slack (esp. via Cinemax aka “Skinemax” and The Playboy Channel), but the softcore boom had gone permanently bust.

Of course, these days the quaintness of much vintage sexploitation is precisely its charm. We may marvel, was anybody ever really [ital] turned on by the likes of Sandy the Reluctant Nature Girl, Mondo Freudo or Flaming Teenage? Yes, they were. And in our current world of jaded “meh,” there is definitely something to be said for the nostalgic appeal of a yesteryear in which it took little more than innuendo and a few inches of bared flesh to make a viewer feel deliciously transgressive.