[Editor’s note: This feature marks the second piece in a six-week Orson Welles series celebrating the 100th anniversary of the filmmaker’s birth. See last week’s story, “Orson Welles: The Enigmatic Independent.”]

There are more published books on Orson Welles than on any other film director past or present.

The above statement is based on my own anecdotal, far-from-exhaustive and thoroughly unverified research, mind you and yes, it’s possible that Alfred Hitchcock tops him (if so it’s a close call), but why let the details get in the way of a dramatic statement? Welles certainly didn’t. Maybe that’s one reason for so many books—there’s so much myth behind the man.

There’s also so much career behind him. Welles made his name in theater and radio as a director, writer, producer and actor before coming to Hollywood, and he had a fascination with complex, contradictory characters who shaped their public images. His debut feature was built on the struggle to find the “key” insight to explain the character and motivation of a public figure and discovering a multiplicity of facets. Welles himself spun fictions around his own story, creating an aura of myth around the “boy wonder” genius that was taken for fact by many critics, while Hollywood (through gossip columnists and trade papers) created its own story: the “failed” genius who defied the system and was brought low by his own hubris. For most of his life, writers were content to print the legend(s), but there was is grist for multiple takes on his life and art in separating fact from fiction alone, never mind challenging clichés and preconceptions that have settled into common knowledge.

Now I should confess that I am somewhat obsessive when it comes to Welles. I own more than fifty books—biographies, studies, monographs, scripts, essay collections—on Welles, and that’s far from a complete accounting. For the vast majority of folks interested in delving deeper into the life and career of Welles, however, one book will suffice, at least as a starting point. The question is where to start?

That depends on a lot of factors, not the least of which is what you want out of a book on Orson Welles. Biography? Appreciation? Interpretation? An investigation of his style and themes? To date there are five major biographies on Welles (six if you count the volumes in Simon Callow’s project separately) and another dozen or so important books that examine the life, career and art of Welles. Thanks to decades of Welles’ mythmaking, dismissive assessments of Welles’ career as squandered genius and projects dismissed out of hand because they were unfinished or unseen, combined with an ambitious artistic career spanning so many arts, there is no single definitive book on Welles, and even some the best works contain factual errors (often, but not always, corrected in subsequent tomes). You could say that, thirty years after his death, Welles research remains a work in progress.

So with those caveats, here’s is my survey of the best, most interesting and most insightful books on the conundrum that is Orson Welles.

The best all-in-one introduction is, in my opinion, Citizen Welles (Frank Brady, 1989), a thorough and thoughtful biography from a writer with no ax to grind and no interpretation to defend. Brady, who is not a film scholar but is a veteran biographer, spent ten years researching the book and approaches his subject with a sense of curiosity and discovery. If he came with preconceptions, it doesn’t show in the book. It does contain some inaccuracies, especially in regards to his later years (a common failing in many Welles biographies), but the extensive research (from primary documentary to interviews with important Welles collaborators and with Welles himself) and breadth of his coverage (especially concerning his work in radio) gives the fullest and most balanced portrait of both the man and the artist to date. Welles historian Jonathan Rosenbaum, who has engaged every Welles biography in critical pieces, doesn’t spare Brady his errors but nonetheless respects the seriousness of his work and greatly favors his biography over Charles Higham, Barbara Leaming, David Thomson and Simon Callow.

On the subject of Rosenbaum, perhaps his single greatest contribution to Welles scholarship is This Is Orson Welles (Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum, 1992), a massive tome constructed of conversations and interviews recorded by Bogdanovich over the course of years. Welles himself edited and even rewrote some of Bogdanovich’s transcripts of the tapes, questions and answers both, which makes this as close to a memoir as we’ll find. Welles’ tinkering held up publication for years and Bogdanovich finally handed the material to Rosenbaum to tame and shape into a career-spanning script. The interview alone would make the book essential but Rosenbaum appends the interview with a detailed career chronology that includes film, radio and theater, plus thirty pages of notes on the interview itself, which fills out many of the topics with additional information. Where the interview gives us insight to the character of Welles, Rosenbaum’s commentary and chronology provides invaluable biography and history.

Orson Welles at Work (Jean-Pierre Berthome & François Thomas, 2006, English edition 2008) avoids biography altogether to focus on the production of his films: the physical and practical details of how Welles made his movies. The substantial chapters take on twenty one separate films and related projects, including unfinished films and, with the help of biographies, interviews, production records and other primary sources, have reconstructed the practical elements of Welles’ filmmaking, from writing to production schedules to cameras and lenses, costumes, sets and locations, to post-production and, in too many cases, the fate of the films taken from Welles’ hands and completed by others. For Welles, more than any director, filmmaking and form are inseparable and every production, like every film, took a different form, by necessity if not choice. This is the essential volume on the creative and collaborative method of Welles, and in addition to the text by French film professors Berthome and Thomas, among the pre-eminent Welles scholars in the world (the book is translated from French), it is one of the most beautiful Welles books as well, generously illustrated with production stills, sketches and reproductions of script pages and production documents.

Leaving biography and production to interpretation and analysis, the richest readings of Welles’ films can be found in Orson Welles (Joseph McBride, 1972, revised 1996) and The Magic World of Orson Welles (James Naremore, 1978, revised 1989). McBride’s book, the first significant American study of the cinema of Orson Welles, was written during the explosion of film studies on college campuses and the rise of auteurism and film books built on close textual readings. McBride’s book is all that, an appreciation of Welles’ film that is thoughtful, detailed and very readable. Naremore’s book is arguably the most beautiful and passionate engagement with Welles’ films you will find on the page. It, too, focuses on deep readings the films but it makes connections with Welles’ politics and his fascination with the showmanship of magic and theater. Both volumes have been revised by the authors to take into consideration subsequent research and discoveries; it allows them to correct errors and expand their readings and perspectives without changing their theses.

These five books form the essential Orson Welles library, in my opinion, but there are many more interesting, insightful and engaging books, from biography to focused studies of individual films, eras or aspects of his art and career.

The Making of Citizen Kane (Robert L. Carringer, 1985, revised 1996) delves deep into the details of the production of Welles’ debut film, from an extensive look at the development of the screenplay through its multiple drafts (disproving Pauline Kael’s lazy claims, in her 1971 essay “Raising Kane,” that Herman Mankiewicz was the primary author with documentary evidence) to a nearly day-by-day account of the shooting, editing, scoring and sound-mixing of the production. Carringer’s thesis is that Citizen Kane represented “Hollywood’s single most successful instance of collaboration,” but he shows how Welles was deeply involved in every aspect of production.

Whatever Happened to Orson Welles? (Joseph McBride, 2006) takes a long, thoughtful look into the final fifteen years of Welles’ life and career. McBride met Orson Welles in 1970 and, in addition to writing one of the first great books on Welles, was on the set of three of his films. This is as much history as criticism and he acknowledges his complicated relationship with the man while making the case that “his old age was far from being tragic wasteland. It was a period of great artistic Fecundity and daring, even if it was largely hidden from the public view.”

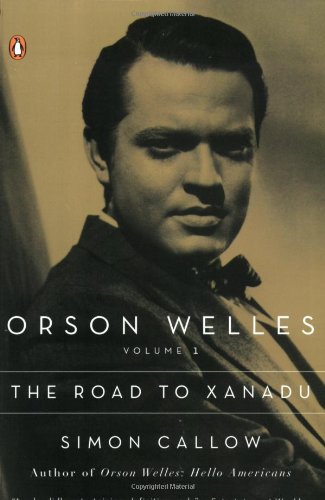

For greater biographical detail, especially in the realms of radio and theater, there is Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu (Simon Callow, 1995) and Orson Welles: Hello Americans (Simon Callow, 2006), the first two volumes into a planned three-volume project (which could run to four volumes given the detail of the coverage). An actor and director on stage and screen in his own right, Callow is fascinated by Welles but, at least in the first volume, relates more to John Houseman, the producer who tries to hold the Mercury Theater stage productions together while Welles blows them apart to see how else they might be put together, and his judgments follow. He’s something of a scold, the theater professional exasperated with the disorganization of Welles as a producer and director, but by Hello Americans, published ten years later after additional research and contemplation, he seems to understand that the madness of Welles’ method is his creative process, that he thrives in free-wheeling environment where chaos and deadlines push him to inspiration and innovation, the very opposite of a studio film production.

Orson Welles (Barbara Leaming, 1985) could be as close as you’ll come to a Welles autobiography, even though he never wrote a word of the book. Rather, he befriended Leaming after she contacted him for interviews, gave her unprecedented access and even appeared with her to promote the book, though it has been suggested that he never actually read the finished book. The greatest criticism the book faced was that Welles had a significant influence on her portrayal of him and his career, but if that’s a misstep, it’s one that makes the book itself more interesting.

Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography (Bret Wood, 1990) is for the Welles obsessive and completist. It’s really more of a resource than a study, a survey of the accumulated knowledge on Welles’ career focused on (but by no means limited to) his filmmaking, and it features both an annotated filmography and bibliography. This was written as a library resource in the era before the web and Lexus-Nexus searches and can be an expensive purchase (and, of course, it is 25 years old) but it is still the best single guide to the published books and articles on Welles before 1990 and it provides notes on the holdings of various collections of papers on Welles. Far more than the casual fan could ever care about but gold to the Welles fanatic.

There are a handful of other interview books, from the valuable anthology Orson Welles Interviews (edited by Mark W. Estrin, 2002) to the controversial My Lunches with Orson: Conversations Between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles (Henry Jaglom, 2013), with its sometimes mean-spirited comments. None of them, however, are as unique and illuminating as Orson Welles and Roger Hill: A Friendship in Three Acts (Todd Tarbox, 2013), a collection of conversations between Welles and Roger Hill, his Todd School mentor, father figure and lifelong friend, edited by Hill’s grandson. These phone calls, recorded with Welles’ permission and blessing over the course of three years between 1982 and his death and 1985, reveal the voice of Welles at ease in personal, intimate conversations and present aspects of his character and nature that no other book does. Along with the transcripts of the conversations, edited into the form of a play (a conceit that works as well as any organizing structure), are letters, essays and other pieces written by Welles when he was a student. It’s quite an achievement, capturing Welles both the boy following his muse into the arts with great expectations and the man at the end of his career, struggling against a reputation that scares producers and investors away yet still driven to create by any means necessary.