Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman makes the distinction between the kind of occupation that takes place everyday in the West Bank and Gaza, and the more “psychological” occupation of those areas—such as Ramallah and Nazareth, where he is from—that were occupied in 1948 and are now part of Israel.

While the obvious signs of oppression—tanks and soldiers in the streets—are absent in the latter, a more internalized occupation has taken hold. “It’s become psychological,” he has said, marked by a “denial of rights” and “humiliation in all its forms.” In films such as Suleiman’s Chronicle of a Disappearance and Divine Intervention, this sense of powerlessness manifests itself in self-destructive internecine struggles, where neighbors dump trash in each other’s yards and sabotage each other’s driveways.

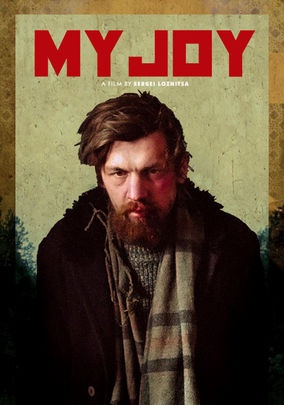

Ukraine is not an occupied territory—at least not yet. Though the country’s southernmost part, Crimea, was recently annexed by Russia, Ukraine has been officially an independent nation since 1991. But judging from the recent narrative films of Belarus-born and Ukrainian-bred director Sergei Loznitsa, the experience of those living in post-Communist states appear analogous to Suleiman’s, where feelings of humiliation, oppression, dysfunction and displacement lurk around every corner—and can often explode into violence. If there was ever a film that might metaphorically express the current political situation on the ground in Ukraine, Loznitsa’s narrative feature debut My Joy might be it.

The film, which premiered in competition at Cannes 2010, begins and ends at roadside checkpoints, an emblematic sign of oppression and victimization (and another fitting echo with Palestinian life). In an early scene, a truck driver, Georgi (Viktor Nemets) is randomly stopped by two traffic police, who have already stopped a woman in a red sports car, presumably in order to extract sexual favors. The guards’ sole purpose isn’t protection, but the abuse of power. And while Georgi gets away, the characters in the film’s final checkpoint sequence are not as lucky.

Despite the appearance of such roadblocks, it’s difficult to delineate their function. What borders do they protect? What routes are they monitoring? There is no way to map any coherent territory in the film. At one point, Georgi find himself stuck in a traffic jam on a no-man’s-land forest road; he then takes a short cut, which only further leads him astray and traps him in a small-town with no escape. Later in the film, two soldiers are similarly lost on highways to nowhere. “It’s a dead-end route,” says one of the soldiers. And that is the point: There is no way to chart My Joy’s Ukrainian-Russian hinterlands; just as its narrative follows several detours, there is no secure sense of space, either.

Despite the fact that film appears to be set in some Slavic nightmare limbo zone, Loznitsa confessed in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter in 2010 that it takes place in the “European part of Russia… the land before you reach Moscow, the territory that saw the events of World War II. It is near the place where Belarus, Russia and Ukraine meet.”

Loznita’s subsequent film In the Fog (2012) is also set in this nether region, straddling the lines between West and East, Europe and Russia, where as many as three million Belorussians were killed during WWII by invading German forces, Soviets and each other. Clearly, Loznita wants to excavate the historical significance of the area. In The Fog explicitly deals with a tale of betrayal and accountability among WWII partisan fighters waging war on the occupying Germans, and My Joy includes two WWII-era flashbacks, which convey the harsh brutality of area soldiers against their own people.

But My Joy, in particular, has resonances for the area’s post-Communist present. Though perhaps linked to the dread of WWII-era devastation—“Time,” Loznitsa has said, “does not exist”—the film suggests there is an enduring sense of dislocation and cruelty that continues to hover over the region. Though Putin’s tanks haven’t rolled across Ukraine’s borders, My Joy shows a people and a place haunted by feelings of futility, distrust and occupation, and the resulting internal combustibility that comes with that existential condition.

During My Joy’s climactic conclusion, it is none other than a high-ranking Moscow police officer and his wife who encounter the terror of another police checkpoint. The guards increasingly scoff at the Russian cop, and when he tries to pull rank, the situation descends further into violence and chaos. It’s easy to read the scene as a kind of symbolic purgative revenge against Russian power. But the sequence and the film ends more enigmatically—it’s not a simple act of aggression against an outside oppressor, but one that is directed just as intensely and self-destructively inward. There is no catharsis in My Joy. There is no victory. Indeed, as the recent events in the Ukraine show, post-Communist independence is a liberty that only goes so far.