Bring up the name Tinto Brass and, if you recognize it at all, the first thing that comes to mind is Caligula, the notorious and grotesque X-rated Roman epic produced by Penthouse magazine publisher Bob Guccione (who also added explicit footage into the already sleazy spectacle). There’s also the Nazisploitation Salon Kitty (the film that earned him the Caligula assignment) and finally a string of lighthearted erotic romps notable for their fascination with the ample derrieres of his usually unclothed leading ladies.

But before he plunged headlong into Eurotica, Brass was a free-wheeling cat mining a vein right out of the nouvelle vague. We’re not talking Godard, mind you, but here was an ambitious young Italian director looking to break out of the comedies and westerns cranked out by the industry by getting young and hip and groovy, dabbling in social satire and pushing the boundaries of film conventions and subject matter.

And thus was born Deadly Sweet (aka I Am What I Am, 1967), a spy thriller turned kooky murder mystery romp. Adapted from a novel by Sergio Donati (a frequent screenwriting partner of Sergio Leone and Sergio Sollima), it plays like a psychedelic Bond spoof directed by Richard Lester. Jean-Louis Trintignant is the out-of-work actor who spots sex kitten Ewa Aulin (the Swedish baby doll of Candy) at a disco and rushes her out of a murder scene and into pop-art playground of shifting film stock, multi-pane split screens, and Mad magazine gags. Brass embraces the creative energy and anything-goes culture of sixties cinema and tosses every pop culture impulse he can grab into the film: comic books, experimental cinema, the French New Wave, the British New Wave, cinema verité street scenes, Antonioni’s Blow-Up (a visit to a photography studio turns into an impromptu fashion shoot), TV’s Batman (Pow!).

The story is incomprehensible, having something to do with a stolen diary with apparently embarrassing disclosures, a dwarf who stalks the photogenic couple through the city, and a group of thugs who kidnap Aulin, strip her down to her undergarments, and tie her up in a kinky scene that evokes Bettie Page bondage stills. It all ends up at “a happening” filled with hippies and social butterflies where Brass films the winding progress of Trintignant and Aulin through the crowd as if it were a concert movie. Aulin, all pouty lips and dazed wide eyes, looks exactly like the kind of party girl to be found at such a counter-culture ball while Trintignant, who mugs it up shamelessly in the comic scenes of this comic-book romp, goes stiff and establishment in the free and freaky atmosphere: the suit lost in the psychedelia. (Both, of course, are dubbed into Italian). It’s not organized and certainly not grounded in any point of view, but that much color and energy and anything-goes spirit is infectious.

If Deadly Sweet is a genre lark with New Wave trappings, Attraction (a.k.a. Nerosubianco, 1969) is a stroll through the sexual revolution, a self-styled “Psychedelic Pop Art Experience” (as the poster promises) with stabs of erotic fantasy and sixties politics. Anita Sanders is a beautiful married woman who steps out for a lazy stroll on a sunny London afternoon and ends up flirting with and fantasizing about a handsome stranger (a smartly stylish Terry Carter, aka Colonel Tigh on the original Battlestar Galactica). There really isn’t a story here, merely a succession of surreal erotic daydreams and music-video digressions (performed by the band Freedom) as she walks through parks, window shops along busy streets, navigates the subway and drinks in the hipster youth culture, while the stream-of-consciousness narration works its way through the sexual politics of the age (a mix of feminism and erotic fantasy).

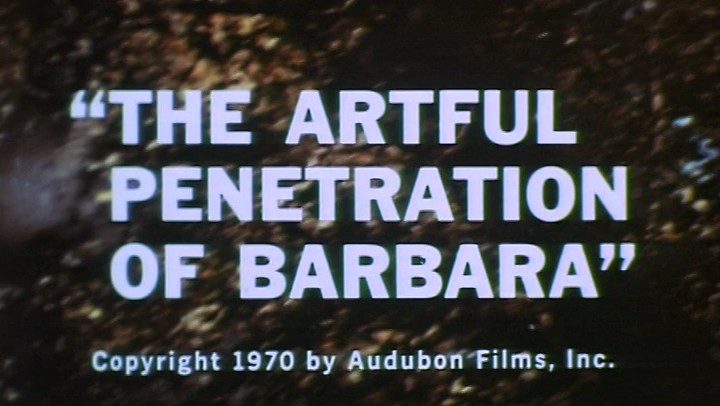

It’s like a rock-and-roll art film by way of a continental skin flick, with pop art posters and Guido Crepax comics interspersed with a newsreel clips of Vietnam and the Holocaust to give it progressive political cred. I’m not sure who he thought his audience was, but it sure is a trippy snapshot of a cultural moment, as well as a preview of coming attractions for Brass. If there is anything approaching revolutionary in this film, it’s the way Brass acknowledges the sexual desires of his heroine and refuses to pass judgment on her efforts to satisfy them. This version is “presented by Radley Metzger” and you won’t believe the title he slapped over the opening shots for American release.

The Howl (1969) may borrow its title from Allen Ginsberg but this is no cry of anguish. It’s a full-on surreal odyssey through a socio-political slapstick landscape. Tina Aumont is a runaway bride who dumps her groom at the altar to run off with a handsome stranger after sharing nothing more than a glance, wandering like Alice through this wild wonderland of talking animals and cartoonish rebels against conformity. This self-conscious puncturing of culture and counter-culture could only have been made in the wake of Weekend and If…, but it’s less political satire than sloppy Keystone Kops chaos with farcical political references. The production looks budget-starved so Brass makes the most of resources, going wild with punctuations of cartoonish violence, bohemian color, ritual cannibalism and oodles of nudity. In the Italian tradition, the sound and dialogue is all post-synched, but even here Brass takes it to extremes, with outsize sound effects and voices that run through the soundtrack independent of the actors, becoming a cacophony that has little to do with the mouths moving on screen.

It’s like he tossed a decade’s worth of cultural protest, cinematic rebellion and caricatures of consumer culture gone wild into the hopper and cut it together as a druggie travelogue. But to give credit where it is due, it is a wildly entertaining and shot with a sense of freedom that disregards even the most rudimentary technical conventions.

After The Howl, self-described radical Brass left his avant-garde experiments behind to push the boundaries of sex in cinema, finally settling in with a series of literary adaptations reworked as sexy erotic romps. And while Brass never showed the political intelligence of Godard, the narrative ingenuity of Resnais, or the lyrical warmth of Truffaut, the films suggested an artist exploring the possibilities of expression. If nothing else, these cultural artifact from the free-form frontier of the late sixties are time capsules driven with an experimental energy and an infectious joy of moviemaking.