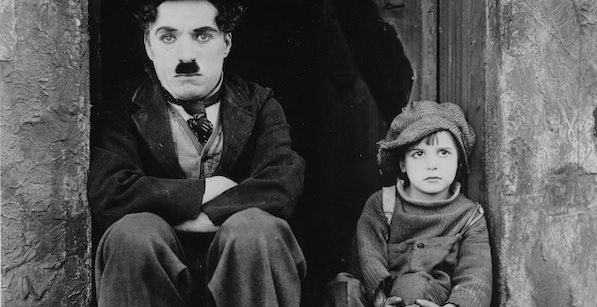

Anniversaries are an annual consideration and nothing seems to resonate more, historically, than a centenary. Many may seem arbitrary but marking 100 years after the introduction of Charles Chaplin’s legendary character, the Little Tramp, is particular cause for cinematic celebration. Events are scheduled around the world over the year ahead but one of the best fêtes occurs January 11th.

Stacey Wisnia and Anita Monga at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival have brought the composer/conductor Timothy Brock to their annual winter one-day silent showcase for performances of The Kid and The Gold Rush. Brock is an ideal choice. Since 1998, he has worked with the Charles Chaplin estate on Chaplin’s scores (first with Modern Times and, thereafter, on every other Chaplin silent feature and numerous short films).

Fandor co-founder Jonathan Marlow was first introduced to Timothy Brock by cellist Robin Boomer, then a performer in the Olympia Chamber Orchestra (which Brock conducted). At the time, Timothy Brock was arguably the finest composer of contemporary silent film scores in the country. Several of his remarkable scores accompany films available on Fandor.

This is the first of a two-part conversation.

Jonathan Marlow: For purely selfish reasons, I’ve wanted you to venture out to San Francisco for many years. How did this particular event begin to take shape?

Timothy Brock: The short answer is that they wanted to do the big version of The Gold Rush at the Paramount [in Oakland], like Napoleon. But it ended up being too complicated, because the orchestra for The Gold Rush is really huge. It’s fifty to sixty players, which I think is considerably bigger than Napoleon’s thirty-five to forty. That is all you can fit in that pit. We ended up wanting to do it in the Castro Theatre after all. Which, to me, was great because I love the theater.

Marlow: The Castro is a beautiful space.

Brock: It reminds me of the Capitol Theatre [in Olympia].

Marlow: It’s very similar.

Brock: I feel very sentimental towards the theater even though I have no real connection with it. We decided to do a version of The Gold Rush that I made for small orchestra (which was initially commissioned by Paul Merton, the British comedian, on behalf of the Chaplins). Subsequently, Christopher Chaplin, the youngest son of Charlie, commissioned me to do a small version of The Kid as well. Which was supposed to be due for later this year, but we just moved it up. I asked him if it was okay if we did it here in San Francisco and he said, ‘Sure, that’s great.’ So now we’re doing both smaller, ensemble versions, for fifteen-to-sixteen players, of The Gold Rush and The Kid.

Marlow: You’ve done the full versions in Bologna.

Brock: Yes. In 2007, we did every Chaplin film there was. In one summer!

Marlow: Goodness.

Brock: That was the end of the project where all of the Chaplin archives were digitized. We did every film live, accompanied by orchestra.

Marlow: Though we’ve known each other for several decades, it was never clear to me–because we never really talked about it—how you transitioned from the period of composing and conducting, primarily, to working with the Chaplin estate. Your exceptional scores for Faust, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which I was fortunately able to present with you in Seattle at the O.K. Hotel, and Sunrise, which I wild-synched at the Grand Illusion for the NWFF’s ‘Century of Cinema’ series… But how did you transition into working with the Chaplin Estate?

Brock: I got a call from the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra in 1998. I’d been guest conducting for the LACO for several years up to that point, doing all their silent films. They said that they were interested in working with the Chaplins to do Modern Times. I was honored enough to know that the Chaplins knew about my work and what I was doing writing for silent film scores as well as preserving period scores (in terms of Carmen and Opus One and things like that). The Chaplins said, ‘Do you want to come out to Paris and take a look at these boxes? They have not been opened since 1936. Take a look and see if you think that doing Modern Times is possible live.’ It was about ten days later and I was on an airplane to Paris. I spent two weeks there just looking over Charlie’s manuscripts for Modern Times. That was an incredible situation. While I was there, before I even got home, they’d bought out my contract with the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and I started working for them directly ever since. Now, this Kid production is the last thing I’ve done for the Chaplins and that makes score number thirteen for them. It’s been a great relationship. It’s been amazing. It also can be rather difficult working with the legacy of Chaplin and his heirs. It has its ups and downs. But, for the most part, it’s been a pretty mutually satisfactory relationship.

Marlow: It’s certainly a life-changing experience.

Brock: When I did Modern Times, they hired me to do Modern Times exclusively for the first three years of its existence (from 2000 to 2003) because Modern Times is extremely difficult to do. There are very few conductors who actually do it now, even after all this time. Doing that essentially allowed me to go to various different cities around the world and then I developed relationships from that. In a sense, it’s Chaplin who helped me expand my career. In the U.S., it’s still considered sub-standard music even though I’ve conducted New York Philharmonic. I’ve done Chicago Symphony (and I do all their silent film programs every year). It’s still considered, in this country, ‘family concerts.’ The United States has a hard time accepting film music as a primary art form. Every major European orchestra does at least one silent film every year as a unique opportunity to hear music as presented in a specific period, like period music. The Vienna Philharmonic has a Baroque festival. They’ll have a symphonic festival. They’ll include a silent film [as representative of a particular period] as well. It’s great for me over there. The doors have certainly opened up in terms of silent film. There’s been a great appreciation for it. Here [in the U.S.], it’s still struggling, even though the resurgence has started over here again. And maybe in London, with Carl [Davis], Napoleon, 1980. It’s slowly…

Marlow: Why do you think in the U.S. it is more of a novelty, whereas in Europe it is treated with considerably more respect? I was quite fond of Chaplin’s scoring as a teenager and yet most folks I knew were dismissive of his work. They thought it was simplistic. I found it deceptively simple…

Brock: It depends on what film you’re talking about!

Marlow: [Laughs.] True.

Brock: If you’re looking at The Kid, for example, which was written in 1972, the music really is quite simple and very sentimental. He had a music director, Eric James, who never questioned what he did and just wrote down strictly whatever ‘Mr. Chaplin’ wanted. Whereas you get somebody like David Raksin, who was instrumental in helping me with Modern Times, even though he was twenty-three at the time [it was composed]. He was a great friend during this process and told me a bunch of stories about how Chaplin worked. He pushed him and subsequently got fired three times. As David said, ‘If you’re a music director and you have not been fired by Chaplin, you’re doing something wrong!’ One of the great things I’ve learned about Chaplin, in doing this, is that… I was a little bit like other people. I always thought, based on reading in his memoirs, that Charlie just la‑la‑ed the music. That he would just come up with tunes and then have somebody else orchestrate, fill it out and make it something that’s really musical from Charlie’s fragmented ideas. In fact, I learned that his hand was in the process from every step, not only the creation of the tunes, the chord structure, the orchestration but the performance as well. In Modern Times, for example, he made music very much like he made his films. He would play something over and over and over and over and over again, by trial and error, and say, ‘No. I don’t like that. I want to do this again. I want the oboe to play the line now, this time, and then the cellos play this.’ The players’ parts have all these chicken-scratches of changes, all dictated by Chaplin and Alfred Newman. It’s just very clear to me, as though he really had the idea in his head—he really had the sound in his head—he just couldn’t put it on paper, like Irving Berlin. Berlin was a song wonder, much less difficult than orchestrating a great palette of color for film. Mind you, this is no slight on Irving Berlin, who was a genius. An absolute genius.

Marlow: Of course….

Brock: What Chaplin was trying to do was much more difficult. And neither one of them could read music.

Marlow: What were the challenges, then, to do a reduction of The Kid when you’re….

Brock: It’s interesting because, with The Gold Rush, the challenges are obvious because the color involved with the orchestration of The Gold Rush is immense. Plus you have so many quotations of other pieces. You’ve got Rimsky‑Korsakov, you’ve got Wagner, you’ve got Brahms, Tchaikovsky. The Kid, on the other hand, is all Chaplin. And Chaplin relied on a sentimental kind of lush orchestral sound. It’s considerably more homogenous than The Gold Rush. It’s got this big, sweet string sound that’s not really. . . it’s hard to describe. But it’s difficult to make that lush, big orchestral sound on a small scale, because he relies so much on size. The Gold Rush relied on size when it needed it but it also was extremely intimate when it needed to be; two or three instruments at a time or a single accordion. That was easier to do, in some ways, than The Kid because The Kid strictly relied on fifty to sixty players playing this big, lush sound and that is much harder to imitate. The idea, then, is to just make the same melodic structure, the same hue and the same kind of colors but on a smaller, more intimate scale without losing the intensity of the music. That’s the challenge. And I don’t know if it works or not because I haven’t heard it yet! [Laughter.] Today’s the first rehearsal.

[To be continued.]

[Continued.]

Marlow: Are you able to rehearse at the Castro?

Brock: No, no….

Marlow: So you won’t be aware of the acoustics of the Castro Theatre until the day of the performance?

Brock: Other than just walking through there (which I’ve done already), no.

Marlow: It’s a great space.

Brock: It’s just such a beautiful place. There are some great theaters that are magnificent to play in but just sound awful. [NZIFF director] Bill Gosden will kill me if he reads this but the Civic Theater in Auckland is one of the most beautiful theaters I’ve ever seen but the acoustics are just terrible.

Marlow: Off-the-record?

Brock: It’s okay. He’ll laugh. He knows it.

Marlow: This happens frequently?

Brock: Yes. When was the Castro built?

Marlow: Timothy Pflueger was the architect. It was built in….

Brock: Silent era or sound era?

Marlow: Early 1920s [1922 to be exact].

Brock: So it was built for silent film.

Marlow: Exactly.

Brock: That’s also true of the Capitol Theater, I believe [built in 1924 and designed by Joseph Wohleb]. Therefore, you get spaces that are still concerned about how the music is going to sound live. Whereas I think the Civic in Auckland was built for sound [constructed in late-1929 and remodeled in 2000]. Anyway, no, we’re rehearsing over in Berkeley. The San Francisco Chamber Orchestra rehearses out there. We rehearsed yesterday and today and then the dress rehearsal is tomorrow.

Marlow: Gold Rush yesterday, The Kid today?

Brock: Correct. Well, Gold Rush yesterday and Gold Rush today (because the score is twenty times more difficult than The Kid). Then we’re rehearsing The Kid at the end of rehearsal today and that’s it. That is typical, though. It is typical to do one to two rehearsals per concert.

Marlow: And you still have time in amongst your Chaplin work and other conducting to compose your own scores as well?

Brock: Yes. I’ve got three really good projects ahead of me. I’ve been commissioned by Vienna to do Frau im Mond.

Marlow: That’s a big piece.

Brock: Three hours! Three hours with a one-hundred piece orchestra. I’m very pleased about that.

Marlow: Goodness. When does that have to be completed?

Brock: The concert is in April of 2015. And I’ve got to compose one Essanay for the Chaplins, which I’m doing.

Marlow: Which film?

Brock: We don’t know yet. It’s for Bologna but they haven’t told me which one they want to do yet.

Marlow: So you have between now and the summer, basically?

Brock: Exactly.

Marlow: At least it’s a two-reeler.

Brock: Only twenty minutes. Still. Actually, I just finished Kid Auto Races. It was joint commission from the Cineteca Bologna and the Chaplins. We recorded it in Madrid five days ago.

Marlow: Where would the recording be released?

Brock: It will be released theatrically as a short to open up for The Gold Rush in February throughout Europe. I’m putting it on the film as soon as I get home. The score of The Gold Rush is a recording I did with the BBC Symphony Orchestra about two years ago.

Marlow: Released in Europe. Not in the U.S. Of course not.

Brock: Of course not. Not theatrically. Again, that plays under the same sort of scenario I was talking about but it is a little bit different. I come to the states four or five times a year, besides doing New York and Chicago’s silent film programs. I’m doing the Montreal Symphony this year. And Boston. I was at the New York Film Festival [with The Gold Rush] in October.

Marlow: I missed you there by two days.

Brock: Kent Jones is an old friend who works with Cecilia [Cenciarelli], my wife. I know that doing orchestral events for film festivals is an expensive proposition. Doing it with the San Francisco Silent Film Festival is not an easy thing for anybody to do. But I’d love to come back again sometime.

Marlow: You’ve done up to Modern Times. You haven’t done any restoring of the sound films?

Brock: The family’s view on it is to leave the sound films alone. Although I’m sort of…

Marlow: You’re torn?

Brock: This is off-the-record.

Marlow: Off-the-record. Agreed.

[Redacted.]

Marlow: How many performances do you do a year at this point?

Brock: It varies. I’ll usually do an average of one-hundred performances a year. Of those, sixty percent are Chaplin.

Marlow: You see that as pretty much the balance for the foreseeable future?

Brock: This year, the percentage is likely to be higher. But, on the other hand, I’m still doing the other conducting. I am still involved with the Entartete Musik (‘Degenerate Music’) series. I’m also doing an Italian Entartete Musik as well.

Marlow: I wasn’t aware of that.

Brock: Many people don’t know about it. There were a number of Italian Jewish composers who were banned during the during the war. And I’m still doing regular concerts as well. I’ve got a concert next week in Basil, for example, of Richard Strauss.

Marlow: Has anyone approached you and said, ‘We love your work. Why don’t you score this new film?’

Brock: A new film? Nobody wants me to do a new film. Why would they? Unless they’re doing something that was particularly up my alley.

Marlow: There are those. But you would be interested….

Brock: Actually, the last person that asked me to do a new film was Kevin Brownlow. I did The Tramp and the Dictator for him. That shows you what the contemporary filmmakers are doing these days!

Marlow: That is entirely totally appropriate, though.

Brock: Of course it is. But that is the type of thing I’m talking about. On the other hand, if somebody wants me to do a new piece—like an opera, for example [a bit of background: Marlow proposed the commissioning of a opera by Brock about five years ago, a speculative project presently in a “holding pattern”]—I’m thrilled to do it.

Marlow: Mudhoney was the last?

Brock: Mudhoney was the last full‑scale opera I’ve done. Fifteen years ago.

Marlow: Time compresses and contracts.

Brock: I know. Fifteen years ago. Damn! That is hard to believe. [Laughter.] I’ve written other musical pieces, of course.

Marlow: If the opportunity presents itself, you will be hearing from me.

Brock: [Laughs.]

Marlow: But, of course, you’d have to find a gap in your schedule. And right now….

Brock: I’d make it!

Marlow: …and the year ahead seems out-of-the-question….

Brock: I would absolutely make the time! That’s not a problem. That’s not a problem for me. I miss it. I miss not having to worry about any kind of time code whatsoever. I miss that a lot. It can be very limiting.

Marlow: When you immerse yourself this fully into someone else’s work, what does that do to you as a composer?

Brock: You have to channel what you’ve got to bring to a project. You’ve got to channel it in the right way. Obviously, when you’re doing silent film, you’re trying to essentially put yourself in the eyes of the director (who can’t speak for themselves; they can only speak based on what you see). If you want to do a historically accurate piece, you have to do as much background work as possible on the director and what were his or her feelings about music and how it works with the film. For the most part, you don’t really know that stuff very well and you have to just sort of act like the director is in the room doing the spotting with you. ‘We need this here, we need that there.’ You have to channel your creative energy in that way, whereas you get a blank sheet both in image and, literally, in time. You are everything and you have to wear all hats at once. In this case, I have to only wear the hat as the composer that serves the director and that director has been dead for decades. I pretty much get to do what I want but I also don’t get to do exactly what I want. It is a careful balance. There are some people where none of this really applies. They just do some amazing things that I never would have thought of.

Marlow: Really?

Brock: Neil Brand is one of those people who can compose music in a way that I never could. He has got a lot of great natural talent to compose in a particular way that I know I could not achieve in that way.

Marlow: As a conductor, what do you bring to these performances that another conductor of the Chaplin scores might miss? For instances, how might the forthcoming [12-April-2014] San Francisco Symphony performance of City Lights differ in the hands of a different conductor [Richard Kaufman, in this case]?

Brock: They’re doing my restoration of it. There is only one restoration of City Lights and it’s mine. I try to be as explicit [in the score] as possible, knowing that I’m not going to be the conductor. But there are many things that are not written down that you have to do and that is mostly in period performance practices. I talk to musicians constantly about it. ‘Listen, you can’t play this like how you were taught to play it. You don’t play it even like your parents. You really have to play it like your grandparents. Or your grandparent’s teachers, even. Remember, this is Hollywood of the 1920s. These are all Austro‑Hungarian string players, so where is that sound? Let’s work on that.’ We work on just the sound of how a string player should be playing from this time period. That’s what I bring as a conductor, a period performance expert.

Marlow: You would hope that other conductors would….

Brock: You would hope that they would bring in the knowledge of how people used to play in the 1920s… the saxophone is doing a synchronized vibrato, for example. The vibraphone should be with the motor running at maximum, not slow ‘Lionel Hampton’ speed but more like ‘Paul Whiteman’ speed. That kind of thing. You need to clue them in to how this would have sounded as Charlie heard it. All the crescendo and all the things that I try to put in the score are there but there is going to be a lot missing if you don’t try to emphasize that type of play. If you just play it straight, if audiences from the 1920s heard it played like that, they’d go, ‘Why is it so dry? Why is this played so….’

Marlow: …lifelessly.

Brock: There’s no life to it. There’s no flexibility. There are no guts to it in that regard. That’s the only thing that I worry about when the music goes out there. I try to include all of that stuff.

Marlow: How often do those performances happen each year?

Brock: The Chaplins are going to be in there promoting their material all the time. There are many conductors out there doing Chaplin. I can only do so many concerts a year. But I think the Chaplins have at least one film of theirs being played once a week somewhere, seemingly.

Marlow: And this year more than usual….

Brock: More this year. Because they commissioned Kid Auto Races, they’ll be doing my music. The Kid Auto Races will screen before many of the features because it’s only six minutes. I know San Francisco is doing Kid Auto Races, too, but the score is for a large orchestra. Here it is going to be accompanied by piano.

Marlow: I have all of the discs that Warner Brothers released a few years back….

Brock: With MK2?

Marlow: Exactly. These are in the midst of being re-released?

Brock: Criterion is re‑releasing everything. They did a really nice release of The Gold Rush, releasing both the sound and silent versions because the family feels that it is important that the sound version is the primary focus. But they included the sound version with the newly recorded score that I did with them and they released it together. There is a nice little documentary in there about Chaplin’s music as well.