Nothing’s quite as canonical by now—or, really, since the sixties—as silent film, an increasingly distant and particular swatch of audiovisual history that now represents less than a third of cinema’s entire legacy. Frozen in film school and in the aboriginal film-history texts, the canon is comprised of roughly sixty features, from The Birth of a Nation (1915) to Earth, L’Age d’Or and Menschen am Sonntag (all 1930), a list that, like any canon, has its fair share of middlebrow yawners, and is also by now calcified into familiarity. But the other thing about canons is that they always leave reams out, and always, always, in time neglected beauties arise out of the archival mists and complicate the picture.

1. The Oyster Princess (1919)

This is what comedy looked like during the era of German Expressionism: positively Burtonesque, satiric of Art Deco, and teeming with startling compositions, none of which ever impedes on the yocks. Ernst Lubitsch’s German silents may be the funniest silent movies made anywhere without a central clown-star to carry them, and this farce is a rip on nouveau riche Americans and Old World royalty, and features what must be the greatest musical-comedy number in the history of silent movies.

2. The Phantom Carriage (1921)

A forgotten classic from the rise of Swedish cinema in the early twenties, this Selma Lagerlof-based morality tale might be Victor Sjöström’s greatest claim to fame before coming to Hollywood in 1924. Certainly, it’s a roiling, vivid piece of work that either heavily influenced the Germans of that decade or shared much of their postwar DNA, in terms of visuals and the Euro-fad for reconstituted classic folktales. A ghost story with a moral axe to grind—literally, it foreshadows Kubrick’s The Shining—the movie is electrifyingly realistic in terms of acting and nuance, while also proudly expressionistic in its inspired metaphysical imagery.

3. La Roue (1923)

Monster epic pioneer Abel Gance was a restless, relentless re-inventor of cinema, and his best films can play like a mad scientist’s laboratory at full crank, filthy with inexplicable angles, double exposures, impossibly moving cameras and crazed speed montages. This massive, tragic melodrama—in its present restored form only a half-hour shy of its original five-hour-plus running time—is about train laborers and the adoption of an orphaned girl, but Gance packs in enough moral agony and mad poetry for three Greek plays, playing out over years and ending up, for real, on the snowy cliff-edges of the Alps.

4. Kean (1924)

A French silent made almost entirely by Russians escaping from the Bolsheviks, Alexandre Volkoff’s fancifully romantic (and quixotic, since it’s silent) biopic of the 19th-century Shakespearean stage idol Edmond Kean is one of the best and most mysterious films about the intercourse between theater and its audience, and surprisingly funny as well. Star Ivan Mosjoukine, resembling Franklin Pangborn morphed with a raptor and imbued with cosmic self-regard, is unforgettable.

5. The Death Ray (1925)

Lev Kuleshov, most famous for the montage experiments that fueled the USSR’s agitprop film industry through the twenties and thirties, was also a devoted pulpmaster, and his hardly-ever-seen may be the most crazed and happily psychotic film from that lost nation’s peak era. Essentially a nutso espionage serial unrolling in the familiar landscape of factory uprisings and budding industry towns, the movie comes off as a scramble of Feuillade and Kenneth Anger, but on fast-forward, flooding with nonstop slapstick, wicked jump cuts, ritualized caricature, raving performances, hidden passageways, surprise disguises, quicksand and on and on. Co-scenarist Vsevolod Pudovkin shows up as a pious priest, but this campy, rambunctious hoot is nothing if not self-satirizing – while blowing raspberries at both trad action serials and collectivist propaganda dramas of the sort Eisenstein made famous that same year.

6. A Page of Madness (1926)

Teinosuke Kinugasa’s first film is not merely the most psychotic Japanese silent film ever made (or seen outside of Japan, anyway), but also the Asian wild card in the avant-garde explosion happening everywhere in the ‘20s. Set in a mental institution amid flailing, dancing lunatics, and offering only a web-thin story about a janitor and his inmate wife (there are no intertitles to help), the movie is really a stream of uneasy images, and with its montage seizures, free-associative mashups and abstracted compositions, it echoes or presages everybody from Dreyer to Picabia to Deren to Lewton. The panicky roving camera seems equal to Murnau’s corpus as of twenty six, but look again at the natural lighting and verite grit, and it’s like you’re looking at celluloid exposed three decades later—it’s a film out of time.

7. Hindle Wakes (1927)

Directed by journeyman Maurice Elvey from a hot and repeatedly filmed 1912 play by Stanley Houghton, this story centers on the Lancashire mill industry and its “bond slaves,” including a few girlfriends who meet up with tragic fates during the “wakes week” holiday. Typical of 1927 nearly everywhere on Earth, the filmmaking is lavishly evocative: imagistic details, Ozu-like still lifes (the factory unattended etc.), a nearly two-minute pan over a surging crowd of dancing vacationers, even p.o.v. shots aboard carnival rides, a year before King Vidor‘s The Crowd (1928). A new DVD soundtrack, by In the Nursery’s Klive and Nigel Humberstone, may be anachronistic, but its mournful arpeggios peg the film as an elegy for lost time.

8. Street Angel (1928)

After Murnau’s famous Sunrise (1927), Fox gave it to Frank Borzage to emulate its aesthetic thrust in a series of stunningly gorgeous, berserkly hokey melodramas, and this Janet Gaynor–Charles Farrell item, set in a studio-set Naples, is merely the least remembered out of a set of diamonds. Viewers then and now have a right to be astonished, not merely by the lambent, fogged-chrome images, but for what might be the most fluid and believable American movie star performances of the silent era.

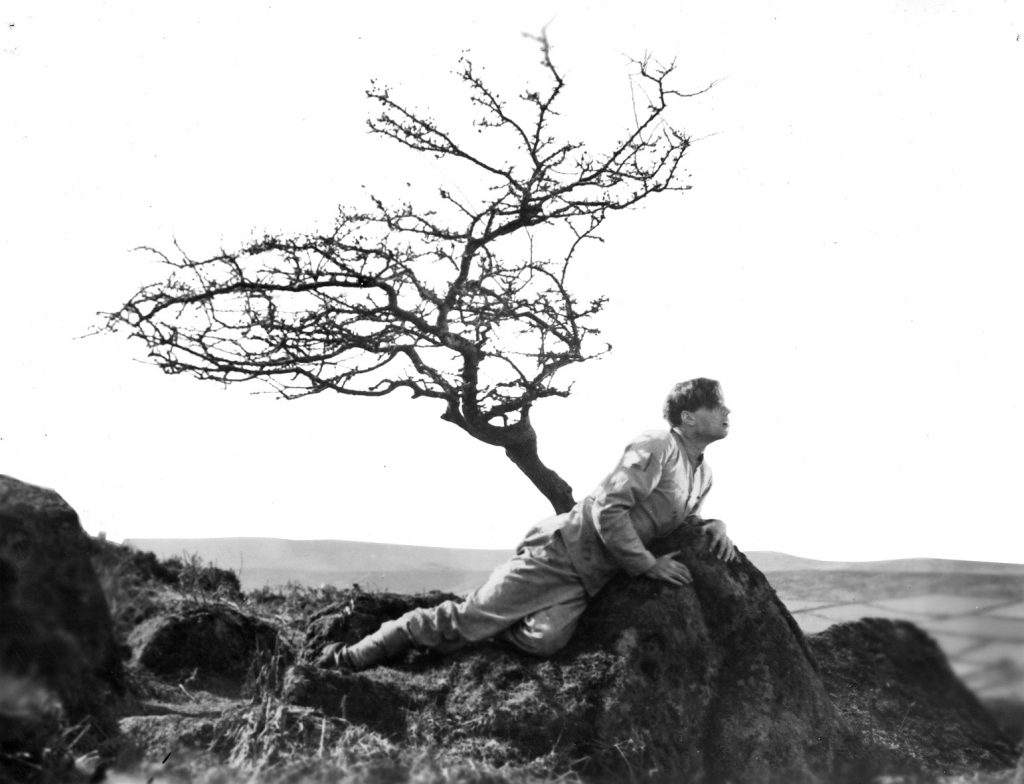

9. A Cottage on Dartmoor (1929)

A kind of modern-Gothic psycho-thriller that is astonishingly frank for its day, Anthony Asquith’s utterly forgotten masterpiece easily stakes a claim as the greatest British silent film of all, and maybe the best British film until after Michael Powell hit his stride after WWII. It’s visually explosive eye glue—the second act’s throat-cutting climax, complete with the dazed razor-wielder absent-mindedly wiping his victim’s blood on his own face, has nothing on an amazing thirteen-minute set-piece in a movie theater, in which we never see the screen, but only the audience, who’s busy trying to learn how to watch talkies.

10. Laila (1929)

A majestic Norwegian epic set entirely in Sapmi, the northern Scandinavian areas occupied by the nomadic Sami (otherwise and derogatorily known as Lapps), this stirring, muscly silent melodrama recalls and bests contemporaneous sagas from Griffith and Sjostrom, and yet outside of Norway it has been all but forgotten. There’s an orphan girl, a love triangle, racial/tribal strife, a plague, a tundra race between reindeer-sleighs and wolves, a canoe chase down a waterfall, and more—all of it staged to exploit the grand, snowy Norwegian landscapes.

11. Menschen am Sonntag (1930)

“A film without actors,” this entrancing, quietly radical artifact of European silent cinema’s last hours takes a Vertovian stance toward capturing modern urban life while mixing in fictive juice, and there isn’t another film made anywhere quite as casually embracing documentary lyricism and detail-stuffed micro-narrative until the early French New Wave. The film was conceived and crafted as a sun-drenched afternoon gambol among friends, the friends being filmmakers Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Fred Zinnemann, Billy Wilder, Curt Siodmak, Rochus Gliese and Eugen Shufftan, even as the movie details the lazy romantic intrigue between four Berliners snacking, napping, swimming, arguing, yearning. Life goes on, beautifully, around them.

12. Salt for Svanetia (1930)

A rare early film by Mikhail Kalatosov that began as fiction, a drama called The Blind, shot in the Georgia highlands of the title, but the Politburo nixed it and forced Kalatozov to reshape it into an agitprop ballade about an isolated, primitive region plagued by ancient ways and eventually saved by the roads built by Soviet industriousness. But of course it’s fiction all the same, reenacted and constructed Flaherty-style, and the visuals are ceaselessly wild and disarming. The Ushguli villages themselves look like sets for The Lord of the Rings, and a late scene in which a mother dribbles breast milk onto the grave soil of her dead baby is hair-raising.

13. Passing Fancy (1933)

The masterpiece from Yasujiro Ozu’s silent days everyone knows is I Was Born, But… (1932), but this pensive comedy is also a must-see, set in and around a low-rent boarding house and evolving into a portrait of a dazzlingly dim-witted single-dad day worker (Takeshi Sakamoto, an infectious presence who acted in 22 other Ozu films) and his bumbling relationship with his impetuous son, which builds to a lacerating and tragic pitch. It may sound small-boned, but visually there’s something mysterious going on here, as Ozu exercises his personality on the camera, the cuts, the actors and the length of shots, and comes away with experiences that feel just as large as our real lives, and just as poignant.

14. Happiness (1935)

One might think that back in the day Soviet filmmakers had two choices—propaganda or the Gulag—but Alexander Medvedkin’s absurdist fairy tale-parable says otherwise. Taking on human foibles as they clash with the ideals of collective-farm community, the film is as bizarrely funny as it is lacerating about both tsar-era economic inequity and the futility of the *kolkhoz*. Medvedkin’s lampooning lark sees weakness and mercenary greed everywhere, to the extent of summoning, in the film’s outrageous compositions, anti-clerical zeal and moments of startling satire (tithe-collecting nuns in transparent blouses, a platoon of soldiers wearing identical cartoon-face masks), the very inappropriate influence of the Surrealists. There’s no record of when Un Chien Andalou might’ve made its way to Muscovite screening rooms, but its footprint is all over this crazy baby.