Born: July 29, 1896, New Haven, CT

Died: March 5, 1957, Beverly Hills, CA

Menzies is one of the few talents ever to work in films whose influence is literally impossible to overestimate. He was almost certainly the greatest and most innovative visual designer ever to work on movies, and there have been many greats in that field.

—Bill Warren

The pictures trapped inside the head of William Cameron Menzies needed a large canvas to be fully realized, and as an art director in Hollywood, he got his chance. His first assignment was The Thief of Bagdad (1924), with Douglas Fairbanks. Menzies shocked the world with his use of colossal buildings in forced perspective and expensive lines of fences, walls and railings to dramatize the legendary chase sequences and create maximum tension. The grandiose debut established Menzies as the king of set design, a reign that lasted for three decades.

No doubt Menzies’s Bagdad earned him commissions on, among others, The Son of the Sheik (1926), Two Arabian Knights (1927) and Fairbanks’s Taming of the Shrew (1929) with Mary Pickford. He was the dominant influence on art direction in the thirties and early forties, quite an achievement considering it was a golden era for production designers; such talents as Anton Grot, Richard Day, Perry Ferguson, Cedric Gibbons and Van Nest Polglase were his contemporaries. Menzies would continue with more influential work on The Dove (1928), which culled him the first Oscar ever awarded for art direction.

The few credits Menzies received as a director were completely forgettable, with a single exception—Things to Come (1936). This science fiction film had a far-reaching impact. Menzies’s directorial techniques in the groundbreaking fantasy spectacle lacked any sign of a personal style, but the highly imaginative sets, particularly those depicting widespread destruction, bear the mark of his production design.

In Things to Come, the screenplay by H.G. Wells called for three distinct variations of the theme’s main setting, the city of Everytown. The first was a bustling metropolitan center, and the second shows the streets of the same city after it is leveled by the effects of a world war. The visual representations of postapocalyptic chaos became the most pervasive view of desolation in film. These images were not yet cliché, yet they have since been repeated in hundreds of futuristic films; the sets of strewn rubble, raging fires, twisted metal and overturned machinery are recalled in The Omega Man (1971), Damnation Alley (1977), Mad Max (1979) and Twelve Monkeys (1995), among others.

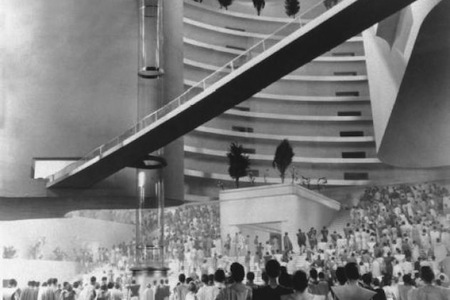

Working with designer Vincent Korda, Menzies needed one final look for Things to Come: the reconstruction of Everytown into an advanced civilization in the year 2036. He resisted all common speculation and trusted his instincts about the way the world would look one hundred years into the future. The result was a utopian city of sleek skyscrapers connected to each other by mid-air walkways, levitating cars and citizens draped in simple robes strolling in peaceful and methodical silence. Things to Come was an unadorned, antiseptic view that has become the most complete vision of a tomorrowland ever filmed, featuring a style of architecture that has become pervasive in science fiction films. Its influence can be seen in other films, notable Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Things to Come relied more on art direction than on crafty storytelling, so Menzies was the right man for the job. It cost $1.4 million to make and opened February 21, 1936, to enthralled fans in London. Other space films like Invaders from Mars (1953) owed much to Menzies’s futuristic design, but with its complete view of the future, Things to Come created a picture of Earth as it might be, and all such films to date borrow extensively from its vision.

More artist than director, Menzies was regarded in his heyday as one of the most influential men in Hollywood circles, and producers would come calling on projects of critical importance, as David O. Selznick did with Gone with the Wind (1939). It was the first time an art director had been listed in the credits as a “production designer.” Menzies painted detailed and elaborate pictures of each scene, complete with correctly garbed actors. Coordinating the entire design team, including set construction and costume design, Menzies worked closely with Natalie Kalmus to ensure spectacular use of Technicolor and hired famed set artist Lyle Wheeler to detail props and décor with historical accuracy. The famous “burning of Atlanta” scene was Menzies’s conception (He can actually be seen playing an extra; there is a band playing as the train returns with wounded Confederates, and Menzies appears on screen in uniform).

Something of a swan song for Menzies, Gone with the Wind won him a second Oscar in 1939 for Outstanding Achievement in Use of Color for the Enhancement of Dramatic Mood in the Production. Although only his standard services were required for Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent (1940) and Anthony Mann’s Reign of Terror (1949), Menzies’s career is still unrivaled for the sheer magnitude of its artistry.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.