Born: May 8, 1920, New York, NY

Died: April 25, 1996, Los Angeles, CA

His animated titles often suggest the theme and the mood of a film, functioning more like a prologue.

—Ephraim Katz

The two most influential events in the development of opening titles are their absence in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and their presence in Otto Preminger’s Carmen Jones (1954). The Jones titles were the work of graphic designer Saul Bass. Bass was an extremely gifted designer with a flair for austere design solutions, which he applied to many of the most memorable product packages and corporate logos; he is responsible for the classic look of Wesson Oil, Dixie Cups, Quaker Oats, United Airlines and AT&T.

While working for Hollywood studios in the 1950s, Bass had noticed how moviegoers tended to linger in the lobby well past the beginning of a film, assuming they had time to purchase candy and soft drinks until the credits passed. Bass got the idea to integrate the titles with the story experience and set out to captivate an audience from the moment the curtain opened. Inspired by the title work of John Hubley in The Four Poster (1952), with its imaginative use of animated text and colors, he created a preface to Jones that hinted at the tension and excitement of the film. Bass had shattered all previous concepts of title sequences in films. As Hollywood began featuring these clever introductions on nearly every film, audiences soon learned to claim a seat well before the movie started.

His stylized cartoon overture for Mike Todd’s Around the World in 80 Days (1956) further secured his international reputation, and soon his art direction was sought for such major productions as Spartacus (1960) and the Cinerama thriller Grand Prix (1966). The long, complicated sequence he designed for Robert Wise’s West Side Story (1961) was shot with the assistance of optical printer pioneer Linwood Dunn. Its incredible number of subtle camera moves had to be succinctly timed and captured in one continuous shooting session. The stunning result was the film credits that appear on the brick wall and buildings of the film’s set.

Alfred Hitchcock’s own interest in graphic design drew him to Bass’s stylish sequences. Hitchcock first used him as a multifaceted visual consultant on Vertigo (1958). Bass’s execution of a spiraling camera, red swirling vortex designs and an extreme close-up of a woman’s face in the titles for Vertigo so impressed Hitchcock that he borrowed the swirl imagery for many touches throughout the film. For North by Northwest (1959), Bass animated a series of lines that move vertically up and down until they eventually fade into a picture of elevator doors that open to reveal Cary Grant in the film’s opening shot. The Master of Suspense also used Saul Bass for help with Psycho (1960). His fragmented typography, slashing lines and swiping bars created helter-skelter patterns that symbolize the personality of Norman Bates and foreshadow the film’s landmark shower scene.

There is a long-standing debate in film circles over the extent of Bass’s involvement with Psycho. In addition to titles for the film, Bass was commissioned to create storyboards for the shower scene, the staircase murder of a private detective and the film’s finale. Apparently, Hitchcock was enamored with the use of shock cuts and montage in the Orson Welles film Touch of Evil (1958) and asked Bass to sketch a series of drawings to suggest how the scenes might be shot. These storyboards are at the heart of a dispute as to who is ultimately responsible for the famous bathroom sequence. The storyboards were recovered by film historians and shot in sequence so a side-by-side comparison could be made against the Hitchcock scene. Clearly, the similarities between Bass’s drawings and Hitchcock’s final cut show that Bass was instrumental in the visual planning of the sequence; Bass later claimed that the director even let him perform some camera work on the set of the shower scene. Crew members and actors, however, especially the film’s star Janet Leigh, adamantly insist that Bass was not around when Hitchcock ordered the cameras to roll. The dispute was aggravated after Hitchcock’s death by assertions from Bass that the shadowy scene of a light bulb dangling over a decomposing body was also taken from an idea he had conceived.

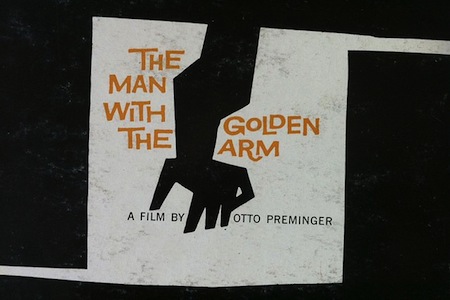

Hitchcock and Preminger involved Saul Bass in many stages of filmmaking, and Bass offered his expertise in every facet of the movie production process. His designs for movie posters, beginning with The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) instituted another sweeping change in the industry. He urged Preminger to approve a design that featured nothing but a single abstract arm jutting from the edge of the paper. The cast and crew were listed in two miniscule sentences along the bottom of the poster. The shocking simplicity was in direct contrast to the traditional movie poster, a cluttered mess of vignettes and headlines. Saul Bass’s clean, bold designs have influenced movie advertising ever since.

After a decade of little impact, Bass’s career was revived when he collaborated with director Martin Scorsese on Goodfellas (1990). His title sequences and special effects in Cape Fear (1991), coupled with the classic track of Bernard Herrmann’s eerie score, showed that Bass still possessed creative judgment unmatched after forty years in films. He created a more graceful look in the flowery images of The Age of Innocence (1993) and finished his last assignment with his finest title sequence, a rousing mix of Las Vegas glitz with fire-and-brimstone dissolves in Casino (1995).

Few film fans are aware of how penetrating the influence of Saul Bass has been. He bucked all conventions to apply his exceptional insight in graphic design to another visual medium. His revolutionary title sequences are a permanent legacy to films. His advertising poster designs are masterpieces that have become sought-after collectibles. His work with the elite directors of cinema has produced images of unforgettable power. Saul Bass was a talented commercial artist who wandered into moviemaking and changed the look of films suddenly and forever.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.