Born: June 22, 1907, Minneapolis, MN

Died: March 22, 1958, Grants, NM

The American public has always responded to the novel, the bigger and, perhaps, the better.

—Mike Todd

In response to the inroads made by television in the decade after World War II, Hollywood studios scrambled to provide moviegoers with a compelling reason to leave the comfort of their own homes. To lure the public back into the theaters, new experiments with 3-D movies, color processes and stereo sound were launched, but they failed to establish a regular following. A Broadway producer named Mike Todd, however, saw an Achilles heel in television’s bid for viewers: television pioneers had made a big mistake in duplicating the proportion of height to width of early films. Todd had invested much of his personal fortune in a new motion picture technology that would give film studios the competitive edge they desired—movies especially made to be projected on screens in a wider format. Wide-screen processes had previously tried, in the late 1890s and again in the late 1920s, without much success, but Todd maintained that his new perfected process would present the theater patron with a larger and grander and more overwhelming experience. The threat of television was believed to be over; the rush to widescreen was on.

Mike Todd was as feared in the entertainment industry as he was respected. A renaissance man with diverse talents, he was best at raising money for new ventures, and those skills led to a role as a producer of plays in 1936. His success on the stage eventually took him to Broadway, and after a rocky fourteen years, he went on to make nearly $18 million from more than sixteen shows. However, heavy borrowing and a gambling compulsion kept Todd close to bankruptcy.

A fateful visit to the 1939 World’s Fair in New York introduced Todd to Fred Waller, formerly head of the special effects department at Paramount, and inventor of a new film projection system that simultaneously cast eleven different images onto a screen curved to a 165-degree angle. The idea was to simulate peripheral vision by engulfing an audience with screen images from ear to ear. The much-heralded exhibit fired a passion in Todd that would consume the rest of his life and bring him his greatest financial success. After starting Mike Todd Productions in 1945, he put his business savvy to work by financing a variety of film projects with some success. He formed a number of limited partnerships to finance his quest of a wide-screen process for more than ten years.

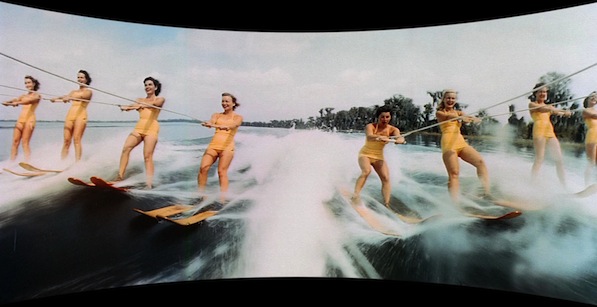

Finally, Waller tried to make a system he called Cinerama more commercially viable by reducing the number of 35mm projectors to three and enlisting the help of a sound engineer, Hazard E. Reeves, to develop a multichannel, directional sound system to go with the wider pictures. To support the experiments, Todd raised money for Cinerama by attracting both the wealth of the Rockefeller and Luce empires. But as time passed, the investors remained unconvinced, and in 1950 they pulled out of the venture. Unable to attract a major studio, the Cinerama group, under Todd’s direction, set out to demonstrate the potential of the process by producing and exhibiting their own independently financed films. The first of these, This Is Cinerama, was introduced on September 30, 1952, at the Broadway Theater. It opened to huge publicity, and crowds lined up around the block for more than two years after the debut.

Cinerama had its shortcomings. Todd was disappointed with the travelogues that were the sole features shown; they were simply simulated experiences of exotic locations without the benefit of a story or characters. Furthermore, the projection of three images created two distracting seams on the screen. Many of the stereo sound processes designed to enhance the experience were poorly implemented, and theater owners were reluctant to install new sound equipment that had not been perfected. To further add to the confusion, Walt Disney and several other studio heads announced wide-screen processes of their own: Circarama, Quadravision, Wonderama and Cinemiracle, to name a few.

In 1952, Mike Todd convinced 20th Century Fox president Spyros Skouras and former Universal chief Joseph Schenck that wide-screen movies would give their studios a competitive advantage against the increasing popularity of television. That year, the three men formed a new Cinerama corporation, and their first act was to purchase the manufacturing rights to the patented work of Henri Chrétien, a French optics inventor. Chrétien had originally applied his ideas to World War I submarines, extending the view of periscopes to 180 degrees wide by developing special convex lenses. He had been adapting these lenses to film cameras as early as the 1920s, working out two distinct parts to the process called anamorphic optics. During the shooting of a film, an anamorphic camera lens squeezes an image onto a film negative. When the film is projected, another anamorphic lens stretches the image and displays the picture in its wide view. It had taken Chrétien more than thirty years to draw Hollywood’s attention to the process that eventually was dubbed CinemaScope.

To improve CinemaScope even more, Todd switched to the wider 70mm film stock, which could hold an elongated 65mm picture while keeping five sound tracks (of 1mm each) available for many of the experimental sound processes of the day. In June of 1954, Todd asked optics maker Brian O’Brien and the American Optical Company to help with prototypes; for their contribution, he named the venture Todd-AO, for American Optical. Ultimately, it would take the expertise of the Bausch & Lomb company to perfect a lens that would reduce distortion, but finally his 70mm process was a complete picture-and-sound system synchronized from a single projector. The first CinemaScope film to display this new process was The Robe (1953), for which Chrétien received a special Oscar for technical achievement.

Todd sold his portion of Cinerama in 1953 to fund other wide-screen spectacles. His Todd-AO company purchased a proven Broadway success and planned to make Oklahoma! (1955) his first solo project, but studio backers wrested it from his control, after paying Todd a $7 million settlement. With the proceeds, he began a mammoth production of Around the World in 80 Days (1956), an adaptation of the Jules Verne novel originally drafted by Orson Welles. Around the World reportedly used seventy-five thousand costumes, 680,000 feet of film, a cast of sixty-eight thousand extras and logged fourteen million air miles of travel. The film marks the origin of the term “cameo,” a small part played by a famous person, in this case such established stars as Frank Sinatra, Marlene Dietrich and Buster Keaton. The film cost $6 million to make, grossed $100 million and won Todd a Best Picture Oscar for 1956.

In 1958, while he was traveling to collect Showman of the Year honors in New York, Mike Todd was killed in a plane crash, leaving his wife, actress Elizabeth Taylor, a widow. Todd was remembered at his funeral as a pivotal figure in the formation of wide-screen, but his lasting contribution would not become evident for years to come. He would change movies in ways he probably never anticipated. The daring showman who championed wide-screen and new sound processes may not have staved off television’s encroachments on movie profits, but he did spark some interesting developments.

When Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey came out in Cinemascope, the 70mm format was found to be critical to the awe-inspiring special effects. Almost all subsequent space epics, including Star Wars, used the larger 70mm film to retain image quality during the multiple exposures of matte photography. Television shows like Star Trek adopted the film stock for special effects. Blue-screen photography and digital computer effects benefit from the higher resolution as well.

*Editor’s note: Last year, we republished the essays of Scott Smith’s 1998 book, The Film 100. The essays were published not as the last word on cinema—as much has changed in film in the past two decades–but as a starting point for further discussion. As our month of lists continues, and Fandor features This Is Cinerama this week, we encourage you to join the conversation. To view the entire Film 100 list and find links to all the essays, please visit Reintroducing the Film 100.

Wide-screen images have now become so popular with moviegoing audiences that 35mm films, which feature a square aspect ratio of 1.33:1, achieve the illusion of wide-screen’s 1.85:1 aspect ratio by a masking process that is created during the projection of most films. When visiting a movie theater, today’s audiences may not be aware that opaque horizontal bars across the top and bottom of the film projector actually prevent the rest of the original film image from making it to the big screen. When these faux-wide-screen movies make it to television, they are again trimmed through a pan-and-scan method before being broadcast to homes. Ironically, nearly 90 percent of all contemporary films projected in today’s movie theaters are still showing 35mm prints, which must be cropped to fill Todd’s popular wide-screen format. And television is finally catching up to the concept of wide-screen; now that letterbox versions of movies are becoming increasingly popular, the proposed HDTV (high-definition television) sets should all but resolve an incompatibility that has existed between television and films since 1952, the year Mike Todd first showed the entertainment industry the shape of the future.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.

More Cinerama-related titles can be found on Blu-ray and DVD at Flicker Alley. Two young couples tour through the U.S. and Europe in Cinerama Holiday. Orson Welles narrates a journey across Australia, Hawaii and the Pacific Islands in South Seas Adventure.