Born: August 6, 1881, Freeport, IL

Died: December 9, 1972, Santa Monica, CA

Nowadays, nearly five hundred ladies and gentlemen of the press cover Hollywood, but in those rip-roaring twenties, I had a monopoly on the news.

—Louella Parsons

Louella Parsons’s love affair with the typewriter began in 1910 when she worked for nine dollars a week at the Chicago Tribune, in the syndication department. At night she wrote film scenarios; through her cousin, she sold her first screen story to the Essanay Movie Company in Chicago. She subsequently took a position at Essanay as a scriptreader for twenty-five dollars a week. Within a few short years, Parsons’s tenacity and bravura would secure her a ticket to Hollywood, but not as a screenwriter. She became a gossip columnist who used the power of the press to command the attention of the industry, eventually instituting a rumor mill that forced movie studios to counter her published opinions with their own publicity campaigns. Before her retirement, Louella Parsons became one of the most feared and respected women in Hollywood. In her more gracious moments, she single-handedly dominated public opinion to such an extent that she sent her vast and loyal readership racing to the pictures she recommended. In her more unscrupulous moods, she was known to fuel the most salacious scandals in the history of cinema.

In 1919, she approached two major newspapers in Chicago and New York about reporting from California on lifestyle issues. The Chicago Record-Herald bit, and later she moved her reports to the New York Morning Telegraph. The job led to a full-time column exclusively about Hollywood, and a year later Parsons was popular enough to warrant an offer from William Randolph Hearst. By writing kind words in her columns about Hearst’s mistress, starlet Marion Davies, Parsons attracted his attention, and he offered Parsons a job reporting on movie news. She demanded and received $250 a week.

Coincidentally, a bizarre incident on Hearst’s own yacht—the death of pioneer producer Thomas Ince in 1924—resulted in Parsons’s most famous assignment. According to her initial reports, an oceangoing celebration of Ince’s appointment as head of a new production company took a fatal turn when Hearst shot Ince in the abdomen during a moment of jealous rage. In the fabricated story, the newspaper tycoon allegedly believed Ince was actually comedian Charlie Chaplin, caught in a romantic embrace with Marion Davies. In truth, no bullet was ever fired and Ince’s death was determined to be the result of chronic liver and stomach ailments, exacerbated by alcohol use. But truth left little room for the mystery and excitement of Parsons’s reports, and she used the nationwide interest in the fatal evening to further her career. Parsons claimed to have been on board the yacht and her reports of the “actual events” had two important motives: to make Parsons herself appear to be a frequent guest at Hollywood’s most exclusive functions and, more important, to steer controversy away from her employer. Many of her unfounded speculations of the night have remained a permanent part of urban legend, and readers around the country eagerly awaited her daily wire reports for any detail of the investigation. The rumors were later debunked, but the tragic event hoisted Parsons into the limelight, and she took on celebrity status that overshadowed many of the famous actors and studio heads involved in the scandal.

As her enormous popularity grew, Hearst had little choice but to make her the first nationally syndicated gossip columnist, a position she practically invented. By March of 1926, Parsons’s columns were syndicated across the country, and within a few years roughly 375 papers were carrying her gossip. Soon, the scope of her influence was international. Among the cafeteria and nightclubs of Culver City, young Louella rubbed elbows with as many industry people as she could, building an intricate web of friends and adversaries that would last a lifetime. Mary Pickford, Gloria Swanson and Joan Crawford would confide in her and conversely benefit from glowing notices in the news. With each new scoop, Parsons muscled her salary up another notch.

Parsons’s column burgeoned into an entire gossip industry. Every rival paper hired its own Hollywood insider, the most notable contender being Hedda Hopper, another old-timer from the studio backlots. Hopper and Parsons began a scoop war that left casualties in the form of reports on fallen stars, broken marriages, lost libidos, fatherless children and the infidelities of everyone remotely connected to Tinseltown. Discretion was not an issue. Getting tips from her infamous collection of informants—hairdressers, hospital orderlies, doctors’ wives and studio assistants— Parsons revealed pregnancies, predicted divorces and offered sympathy directly through her columns in the press. To a gossip-hungry public, she announced the marriage of Chaplin to eighteen-year-old Oona O’Neill, revealed Grace Kelly’s and Ingrid Bergman’s lovers and exposed Joseph Cotten’s adulterous affair.

Parsons was truly feared by stars and studios alike; they thought she was capable of swinging Oscar nominations and wins through public support, and they knew she was prone to vengeful acts against stars she deemed even slightly uncooperative. She insisted on interviews from the latest stars, demanded advance screenings of highly anticipated films and bullied studio executives with threats of negative press when she didn’t get her way. Her wrath was especially felt by those actors who refused a dinner invitation or skipped out early on one of Parsons’s parties. “If you were part of the movie business, you could not ignore her,” actress Jane Greer remembered. “The recurring nightmare among actors in Hollywood was to be invited to Hedda’s and Louella’s on the same night.”

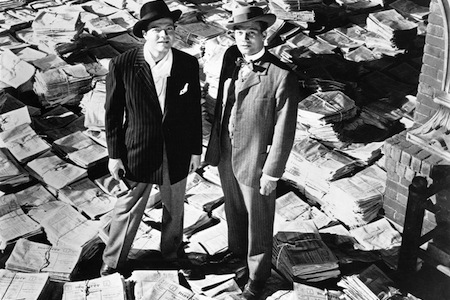

The most famous object of her retribution was Citizen Kane (1941). When Parsons heard a rumor that her employer was the subject of the film’s satire, she demanded that Orson Welles give her a private screening. When he refused, she leaked vicious tirades in print against the young director until he relented and showed her the film. Hearst never had a more devoted ally than Parsons, and her efforts were instrumental in sinking Kane. She threatened RKO studio heads with nasty and salacious exaggerations in print, and called Radio City Music Hall in an attempt to convince theater owner W.G. Van Schmus to cancel Kane’s premier on the threat of no newspaper support. RKO and Welles outsmarted her, however, by using the blackout to their advantage in the now famous Welles exclamation: “The film Hollywood doesn’t want you to see.”

Another sign of her enormous influence was the sheer number of people who took her advice. A survey outside some New York theaters found that eighty percent of moviegoers were standing in line waiting for a film simply because of Louella’s favorable notices in broadcasts. A 1949 poll ranked her as America’s best-loved woman commentator, and Parsons cashed in on her fame quickly. She toured with a stage show called Louella Parsons’ Stars of Tomorrow, published a scandal-riddled autobiography and made regular radio broadcasts of her columns. The radio program, Hollywood Hotel, included advance notices of upcoming films and celebrity interviews. Later, her gossip columns were a staple of Photoplay, Modern Screen and Motion Picture magazines. Eventually her name drew such a loyal following to these publications that, overwhelmed, she had the articles ghostwritten.

Louella Parsons’s effect on Hollywood was significant; she forced studios to rethink the way they packaged their films and stars before presenting them to the public. Almost single-handedly, she initiated a lucrative market for entertainment news that has existed ever since. By the 1950s, studios had learned to counter gossip reporters by establishing huge publicity departments to “handle” the press. Still, Parsons’s legendary tenacity enabled her to capitalize on public interest and keep Hollywood firmly under her thumb for thirty years. As teenagers became an increasingly dominant market segment in the sixties, Parsons’s appeal faded, and her failing health eventually forced her to retire. She ranks among a handful of journalists powerful enough to make studios take notice and change the way in which they market their films. The “queen of the trades,” she was a self-styled propagandist who wielded her considerable influence on movies through the role she alone invented—the Hollywood gossip.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.