Born: August 25, 1879, Addison, MI

Died: October 10, 1978, Bridgeport, CT

The first successful cartoonist to become a successful cartoon producer.

—Leonard Maltin

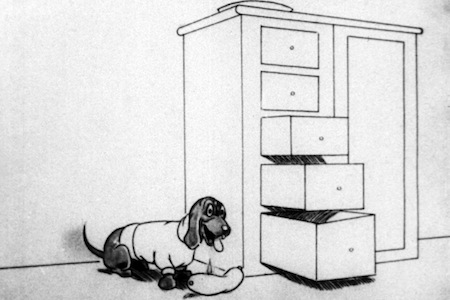

The first animated cartoon to contain a structured story, The Dachshund and the Sausage (1910), is credited to a young newspaper artist named John Randolph Bray. By day he worked as a senior artist on the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and at night he fiddled with the idea of giving life to his drawings. But it was not artistry that would endear J.R. Bray to legions of animators, it was inventiveness. While moonlighting one evening, Bray toyed with sketches he had draped over a lampshade and was struck with the idea of making a drawing process that would prove fundamental in making animated films commercially feasible.

At the beginning of the century, animated films were a tremendous drain of time and energy. Each character had to be drawn on individual pieces of paper in a series of slightly progressed poses, while retaining a consistent look throughout. Then, a tedious task would ensue: a background of scenery would have to be hand-drawn over and over again on each sheet of paper. The more elaborate the scenery, the more time-consuming the work. The number of hours required to complete just a few seconds of screen time made any prospect of profiting from cartoon distribution an utter impossibility.

By 1914, Bray had devised a system whereby a single image of scenery would by printed on hundreds of sheets of tracing paper, eliminating the need to duplicate backgrounds by hand. Then, after animating his characters on plain pieces of paper, he would overlay the translucent scenery onto the cartoons, giving the appearance of a cohesive scene. However, after these drawings were filmed, the trees and mountains of the background seemed to jitter when projected onto a screen. To fix this, Bray established one of the first important conventions of quality animation—registration pegholes. Most animators of the day were filming stacks of drawings by lining up their edges against the inside of a box. This was not a reliable way to ensure perfect alignment. Bray pushed two stubby hatpins through a piece of pressboard, turned it over, and puncturing each sheet in two separate places, he secured them for drawing. Each successive piece of tracing paper would be punctured directly over the previous sheet, and the artist would draw on top of his last illustration. When the drawings were all completed, Bray mounted a camera directly over the table, pointing it down in the direction of the pins and threaded each drawing back through its original holes. The system worked magnificently. Bray’s cartoons contained the steadiest images to be found anywhere.

He then joined with Earl Hurd, another newspaper cartoonist, who had independently experimented with a similar process using clear celluloid sheets instead of translucent paper. Hurd’s approach differed from Bray’s in that the background was a static painting and the characters were inked onto the celluloid material, called cels. Bray shared his peghole registration technique, and together the two men had the makings of a cel-based animation process that could reduce production cycles enormously and cut costs dramatically. Their first cartoon short, The Artist’s Dream (1913), proved that the method was a sound success. Suddenly, animated cartoons were no longer a labor of love for starry-eyed cartoonists to create in their spare time. They were an industrialized product.

To capitalize on the idea, Bray first showed the process to Pathé Films and promised to roll out a steady supply of cartoon shorts. Studio head Charles Pathé was thrilled and contracted Bray to create the first animated cartoon series. Colonel Heeza Liar (1914) was based on a fashionable comic strip about an adventurous braggart, a thinly disguised caricature of Teddy Roosevelt. Bray did the first sketches himself but later hired young Walter Lantz, the soon-to-be creator of Woody Woodpecker, to complete much of the animation until 1916. As commissions for more cartoons poured in, Bray began to hire almost any artist who could hold a pencil. Animation experience was not required, and Bray preferred to teach the cel process to fresh thinkers. Many of the world’s finest animators, including Max and Dave Fleischer, got their start in the Bray studios. He invited his competitors to learn the process, even offering to train many of their animators at night. There were naysayers who doubted the efficiency of the Bray-Hurd system, but it quickly became the standard for cartoon production, spreading to every animation studio in the world. In fact, Bray’s 1914 patent on the process forced every studio to pay a licensing fee and required every cartoon made until 1930 to include in its opening titles the phrase “Licensed by Bray-Hurd Process Company.”

Bray enhanced the cel method further with the introduction of multiple layers of celluloid, each carrying a separate element of the scene. For example, if two cartoon characters entered a scene from different edges of a frame, each character was inked onto his own celluloid sheet. The two sheets would be placed in register over the background painting and appear as a single integrated picture. The beauty of the multilayer method was that Bray could assign a dedicated illustrator to each character in a scene, once again reducing the time it took to finish a cartoon. By 1922, Bray’s studio became a forerunner of the modern assembly-line process, separating tasks—like inking and painting, for example—into distinct departments. Other animation studios were stymied by his pace.

Artistically, Bray’s studio never matched the level of his competitors; the skills of his illustrators were generally poor, and the stories were second-rate. Even his lone attempt at developing a franchise personality, The Debut of Thomas Cat (1920), was not memorable. But the financial success of the Bray studio allowed the artists time to experiment, and the introduced a number of sophisticated firsts for cartoons: the use of gray tones, camera dissolves between scenes, iris close-ups, surreal gags and even live-action integration long before Max Fleischer’s studio made it famous.

But the greatest gift was the cel process itself. Its basic concepts—independent movement of objects, and overlapping levels of action—have been utilized in every facet of filmmaking. For the next sixty years, almost all title cards and screen credits were achieved through some variation of the cel process. The principles of cel animation easily applied to other assembly techniques used in special effects departments; the optical printer uses a variation of the method to sandwich images together before filming. Ultimately, the multilayer concept would even be applied to many of the computer software programs that produce today’s special effects.

The cel process alone accounts for Bray’s lofty position in this ranking. Without it, the entire animation industry would not have been commercially viable, and the areas of special effects and title sequences would have been dramatically limited in their ability to produce many of the cinematic experiences we see daily. Additionally, the division of labor that Bray instituted in his studio became the worldwide model for the mass production of animated shorts; the separate tasks performed by animators has remained relatively unchanged. Bray’s other technical innovations also support his reputation as one of film’s most significant pioneers.

An ironic footnote to Bray’s contribution to cartoons is the explosion in the late 1980s of vintage hand-painted animation cels as collectible items. As you read about one of these original cels being auctioned off for thousands of dollars, consider the many sheets that were discarded or unwittingly wiped clean after their initial use over seventy years ago.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.