Born: April 9, 1830, Kingston-upon-Thames, England

Died: May 8, 1904, Kingston-upon-Thames, England

Edison, Muybridge, Lumière, are all monomaniacs, men driven by an impulse, do-it-yourself men.

—André Bazin

The story is legend: California governor Leland Stanford makes a bet with Dr. John D. Isaac, in 1872. Stanford wagers $25,000 that at a certain point during a fast trot a racehorse will have all four legs off the ground simultaneously. After commissioning the services of experimental photographer Eadweard Muybridge, Stanford wins the bet and sparks a motion picture revolution. A nice story, but unfortunately it’s not entirely true.

Stanford was not the state’s governor at the time. Isaac did not take the bet. And Eadweard Muybridge wasn’t actually Eadweard Muybridge. His real name was Edward James Muggeridge; he was a well-respected photographer whose stills of the Yosemite Valley in 1869 and advances in camera shutter design had made him famous in the growing circles of amateur photography. Muybridge was perhaps the perfect candidate to solve the dispute; he was a relentless, pragmatic thinker who addressed each task with laborious attention to detail but worked quickly as well. His first successes were widely praised landscapes of the Yosemite Valley and detailed, panoramic compilations of early San Francisco, but these lacked any creativity. Muybridge’s interest in the emerging craft seemed more scientifically experimental than artistically expressive. His approach to photography was straightforward, and what remains of his extensive collection of human and animal photos are cold, clinical examinations of forms in motion, completely devoid of any dramatic lighting effects or unusual point-of-view angles.

In appearance, he was an odd figure of a man, with gangly arms and gaunt features. His bizarre mannerisms and long-winded rhetoric, rumored to be the result of a head injury he sustained in his youth, made him a source of social ridicule and further contributed to his reputation for eccentricity. Muybridge was infamous in the San Francisco Bay Area of the 1870s, having been the defendant in a well-publicized murder trial, at which he was exonerated. After the lengthy and expensive trial, Muybridge approached Leland Stanford about conducting experiments in exchange for room and board, and the two men struck a deal.

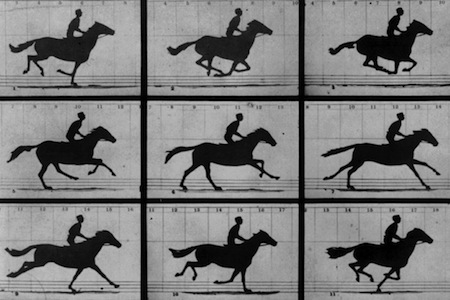

Stanford’s real interest was in studying horses closely enough to understand their behavior in motion. By doing this, he hoped to improve the breeding and training methods he used for his racehorses. What Stanford needed was the shutter technology that only Muybridge had. Muybridge had pioneered several key developments in the area of automated mechanisms for cameras. Previously, film exposure was achieved by hand; as a subject posed perfectly still, the photographer would carefully remove the lens covering, then quickly replace it after the right amount of light was captured. The trouble most photographers had was estimating the right amount of exposure time for different situations. But the sophisticated Muybridge devices could be triggered to open and close a shutter quickly, allowing multiple exposures. This technology was explained to Stanford by Muybridge, who had aspired to solve the burning question of the equestrian by galloping a horse in front of a row of twelve cameras while the shutters captured consecutive positions in the horse’s gait. In May of 1872, Muybridge was successful in securing a sequence of still images, darkly lit silhouettes revealing that the horse’s hooves were all airborne at once.

Because the typical shutters that Muybridge had originally designed were a bit slow for capturing successive phases in the horse’s motion, he made improvements. He looked for a trip mechanism that would time the shutters with the horse’s legs. Borrowing principles used in the production of railway telegraphs, Muybridge devised a system that opened the shutters much faster. Finally, Muybridge rigged his equipment on a deserted Sacramento racecourse with several cameras placed low to the ground and triggered by a trip wire. The new contraption was tested in 1877, when Stanford’s favorite horse, Occident, tripped the tiny wires at full speed. Muybridge continued his series photography, expanding the number of cameras to twenty-four and improving shutter speed with a system of magnetic releases that gave an exposure every two-thousandths of a second. He then proceeded to capture the stride of many different animals. Soon, these photos would reach all corners of the world.

In 1879, Muybridge adapted these images to a popular children’s toy called the “wheel of life,” or Zoetrope. The Zoetrope was an optical illusion toy, very much in vogue at the time, that worked on a scientific principle to create a phenomenon dubbed “persistence of vision,” the ability of the human brain to blend a series of still pictures into a continuous stream that emulated lifelike movement. Muybridge had something unique. The Zoopraxiscope, first demonstrated in Stanford’s home, became the forerunner to early projection devices like the turn-of-the-century nickelodeons.

Meanwhile, his pictures were widely published as still photographs; they might have remained no more than interesting oddities if they had not caught the attention of Laurie Dickson, the laboratory assistant Thomas Edison had assigned to study Muybridge’s work. Seeing the Zoopraxiscope in operation gave him definite ideas of how to best apply its principles to moving images. These demonstrations strongly impressed Edison, and he agreed to let Dickson incorporate the shutter mechanism into motion picture equipment. High-speed shutters became an integral part of the first motion picture camera.

Muybridge became an instant celebrity from the event, recognized for his vital achievement. In 1887, he returned to his native England and set out to publish an astounding eleven volumes of his experimental still photographs, methodically recording the natural movements of hundreds of animals as well as a diverse collection of humans involved in various activities. These books became the authoritative guide for animators, who still study the photos for anatomical accuracy. Toward the end of his life, Muybridge tinkered with new technologies and continued to lecture well into his seventies. Ironically, he was not fond of the early motion pictures he saw and could barely sit through a seven-minute short.

Muybridge’s ranking may seem rather low considering his seminal work in shutter technology and his vast dissemination of his findings through extensive lectures worldwide. However, several significant technologies were required to integrate the principles that Muybridge discovered into a usable film camera-and-projection system. Furthermore, the other producers, directors, performers and technicians that precede Muybridge here were all vital contributors to filmmaking’s evolution into the art form it is today. Fittingly, Muybridge falls just behind special effects pioneer Linwood Dunn, who shared with this legendary man a curious, persistent spirit that wrestled with a basic limitation in photography, finally uncovering a revolutionary new way of bringing images together to create something quite magical.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.