Born: May 31, 1930, San Francisco, CA

From laconic TV star to laconic genre star to laconic superstar.

—Michael Barson

The Old Western was taking a beating in the 1960s. American New Wave directors like Sam Peckinpah and Arthur Penn attempted to revisit the genre and demystify the allure that stalwarts John Ford and John Wayne had spent years solidifying. Overseas, a new actor was interpreting the gunslinger as the nameless hero of Sergio Leone’s “spaghetti” westerns. Clint Eastwood would rise though a career of cowboy roles to carry Wayne’s torch to a new generation of film lovers. His performances in more than fifty films have left a permanent mark on action roles, and today’s macho screen idols are indebted to him for much of their style and delivery.

Editor’s note: The essays of Scott Smith’s 1998 book, The Film 100, are being republished in their entirety here on Keyframe, not as the last word on cinema, but as a starting point for further discussion. Please join the conversation. To view the entire Film 100 list and find links to all the essays, please visit Reintroducing the Film 100.

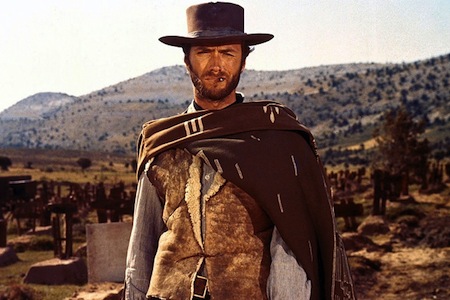

Eastwood shared billing with a talking mule in Francis in the Navy (1955), and his first significant role came in Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Originally titled The Magnificent Stranger, and based on Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961), it was the debut of the fearless loner that Eastwood would portray in other Leone westerns shot throughout Spain, Germany and Italy. For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) were solid hits in Europe and eventually reached cult status in America. Eastwood, fresh off the trail as Rowdy Yates in television’s popular series Rawhide, seemed a perfect choice for the postmodern films, playing a moralistic cowboy out of place in a snakepit of nasty caricatures.

Back in the States, Eastwood made Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970) and The Beguiled (1971), establishing himself as the heir to the cowboy throne vacated by the ailing John Wayne. Ironically, these films were directed by Don Siegel, who helped Wayne make a graceful exit in The Shootist (1976).

The nihilistic overtones of the Eastwood persona took shape under Siegel’s hand in the first Dirty Harry (1971) and grew in its four sequels directed by others (with Eastwood himself directing and producing the third). The title role was offered to John Wayne, Paul Newman and Frank Sinatra before Siegel settled on Eastwood. The films about the driven detective Harry Callahan were a backlash against sixties liberalism; feminists and pacifists attached misogynistic and right-wing connotations to the film’s ultra-conservative values.

At the height of the feminist movement, Eastwood became the model of masculinity. His laid-back manner and independent spirit were expressed by an economical acting style. His characters spoke only when necessary and revealed their feelings reluctantly. Anything else that needed to be communicated was usually handled in the script with Hollywood’s oldest and most frequently used prop—a gun. The liberal bias of the times did not stop Eastwood, and he stayed on the top of box office and celebrity polls for the next twenty-five years.

Eastwood became a respected director himself with Play Misty for Me (1971) and almost single-handedly kept the western alive throughout the decade, starring in, as well as directing, Joe Kidd (1972), High Plains Drifter (1973) and The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976). He became the biggest name in westerns since John Wayne, but their acting styles were markedly different. Where Wayne was direct and aggressive, Eastwood was reluctant and lazy. Where Wayne was charismatic and kind, Eastwood was terse and cold. To combat the widespread perception that his range was limited, Eastwood accepted a number of roles in broad comedies and dramas.

Eastwood tried to revitalize the western with Pale Rider (1985), but without success. However, Unforgiven (1992) became a critical triumph as well as a solid $100 million commercial hit. From a script Eastwood had secured in the 1970s and left undeveloped for over fifteen years. Unforgiven was a morality tale set in the West that seemed to defy a postmodern label. It had a new western look, not as antiseptic as John Ford’s films and not as gritty as Leone’s. It was not particularly romantic, nor was it a sly wink at the past. Essentially it was an elegiac film that restored the power of the genre. It was selected as best film of the year by the National Society of Film Critics and won the Directors Guild Award in 1992. It also collected four Oscars, including Best Picture and one for Eastwood as Best Director.

Today’s screenwriters and action stars work diligently to copy his immortal one-liners, steely delivery and box office success. Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis, Steven Seagal, Jean-Claude Van Damme and Chuck Norris all rely heavily on the Eastwood influence, muttering glib one-liners under their breath and restricting themselves to minimalist facial expressions—squints, lip curls, gritting teeth (Leone once said of Eastwood, “He had only two expressions—with a hat and without a hat.”).

In four different decades, Clint Eastwood has consistently performed among the elite ranks of superstars. He had an unprecedented twenty-year run in the annual Quigley poll of theater owners’ top ten box office draws, and on the overall list of the top draws since 1933 he is preceded only by the Duke. He is the rare action star who has escaped stereotypical roles by financing his own highly artistic endeavors with paychecks earned from his macho roles. And like the Duke, Eastwood is still a leading action hero well into his sixties; In the Line of Fire (1993) and Absolute Power (1997) were both $100 million blockbusters.

To read all the republished articles from ‘The Film 100,’ go to Reintroducing the Film 100 here on Keyframe.