The “Kuleshov Effect,” as explained by Alfred Hitchcock to François Truffaut:

[Rear Window] was a possibility of doing a purely cinematic film. You have an immobilized man looking out. That’s one part of the film. The second part shows what he sees and the third part shows how he reacts. This is actually the purest expression of a cinematic idea. Pudovkin dealt with this, as you know. In one of his books on the art of montage, he describes an experiment by his teacher, Kuleshov. You see a close-up of the Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine. This is immediately followed by a shot of a dead baby. Back to Mosjoukine again and you read compassion on his face. Then you take away the dead baby and you show a plate of soup, and now, when you go back to Mosjoukine, he looks hungry. Yet, in both cases, they used the same shot of the actor; his face was exactly the same. In the same way, let’s take a close-up of Stewart looking out of the window at a little dog that’s being lowered in a basket. Back to Stewart, who has a kindly smile. But if in the place of the little dog you show a half-naked girl exercising in front of her open window, and you go back to a smiling Stewart again, this time he’s seen as a dirty old man!

It is in no way surprising that Hitchcock in describing this experiment invariably focused on the capacity of film editing to make us into voyeurs, or, more specifically, “dirty old men.” But that’s a story for another time. The early work on film editing done by the Soviet teacher and filmmaker Lev Kuleshov is central to our understanding of stylistic convention; in this column, we’ll look at two of the narrative films he made as a director, to see how he practiced his own principles, and to see what we can discover about the premises behind them.

This particular exercise carried out by Kuleshov is frequently cited as the first articulation of one of cinema’s foundational principles, which is that films and their audiences collaborate to impose spatial, temporal, causal and even associative meaning on a series of discrete shots. But there is some baggage that comes along with this. For instance: acting. The performance styles utilized by Kuleshov in two films he directed, By the Law and The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, are hardly some merely functional components necessary for the construction of meaning by montage. In particular, Aleksandra Khokhlova, Kuleshov’s wife and frequent collaborator, works her way up to a pitch of eye-bugging greasepaint hysterics and spends nearly the entirety of both films there.

In fact, the montage theory of Eisenstein, himself a former student of Kuleshov’s at the Institute of Cinematography, derived from his experiences in the theater, for which he favored a notably histrionic performance style. Eisenstein’s montage theory, with its talk of shots as “building blocks” or “cells” and the creation of meaning through their “collision,” evolved out of his “theater of attractions,” of mobilizing and politicizing the audience member by working on him through every available expressive means. The forced juxtaposition of these different attractions, as studied by Kuleshov, was an extra arrow in cinema’s quiver.

Another sign of cinema’s evolution out of the theater evident in By the Law (1926) is more immediately evident to Western eyes: namely, the reliance on proscenium staging.

For much of its running time, By the Law could in fact be a play, with a small cast on a single set: a gold prospector, his pious wife, and their prisoner—another member of their expedition, who goes on a rampage and kills two of their comrades before he’s captured—are trapped in a remote cabin by the spring flooding of the Yukon. Aside from the obvious arrangement of the cast around three sides of a table, which he uses on a couple of occasions, Kuleshov largely films from in front of the fourth wall. Significantly, when he cuts in closer, he prefers frontal close-ups, emphasizing the “attractions,” the performances of Khokhlova and others.

Kuleshov is able to edit in this fashion, rather than in the classical Hollywood style of establishing space through eyeline matches into offscreen space, because we maintain a mental picture of the dramatic space already cued for us by the early establishing wide shots of the whole location. This is one manifestation of editing as a collaboration; that we also infer a dramatic space to correspond with the action when one is not established for us is the conclusion of another of Kuleshov’s early experiments, in which shots of two actors in different parts of Moscow build to a meeting on a city street, and a look offscreen to the White House.

We also maintain a mental chronology, it would seem. Parallel editing in By the Law both creates suspense, by cuing us to anticipate the convergence of two lines of action, and allows dramatically redundant material to be elided. In one sequence, the husband and wife bury their slain comrades in a blizzard, while, back at the cabin, the killer struggles to escape. Labor, both the husband and wife’s full trudge through the snow, and the murder’s straining against his ropes, is depicted with just enough duration to get the message across, and doesn’t seem obviously condensed because the action is not shown from start to finish. Here, screen time, like screen space, may not be strictly continuous, but we don’t need it to be.

Kuleshov’s cross-cutting also suggests the influence of an American pioneer, D.W. Griffith, emphasized by some unfakable elements of natural spectacle, particularly the ice floes rushing past the exterior of the half-submerged cabin. In fact, By the Law, adapted from a Jack London story, is very close to the kind of Western genre film parodied in Mr. West (1924). That film, from two years earlier, shows Kuleshov’s sincere interest in montage as the basis for an immersive narrative world. The film is explicitly explicitly political in intent, and satirical in tone: over the objections of his fearful wife, bespectacled Mr. West (Porfiri Podobed), a local YMCA president, travels to Moscow to see the Bolsheviks, with a suitcase full of stars-and-stripes socks. There, despite the presence of his rootin’ tootin’ bodyguard Cowboy Jeddy (future director Boris Barnet), he falls in with a crowd of dissipated aesthetes and fallen aristocrats (played by Pudovkin and Khokhlova, among others), who plot Red Scares to separate the susceptible Mr. West from his money. Will Mr. West’s eyes be opened to the real glories of the new Soviet state, before it’s too late?

But although sending up Western attitudes and genres, Kuleshov nevertheless shows a deft hand for action scenes, integrating wide shots and tightly linked close-ups to showcase impressive stuntwork on Cowboy Jeddy’s slapstick automobile, motorcycle and horse-drawn carriage chase through the streets of Moscow.

Kuleshov’s evident skill here, which consists in not confirming rather than disrupting our sense of the chase as spatially and temporally continuous—those more familiar with Moscow street geography are free to disagree, I suppose—leads us to mark a curious moment earlier in the film. Cowboy Jeddy is sitting in his room, taking target practice at glass bottles lined up on the wall opposite. In the first shot of the sequence, he fires once, offscreen right; in the next shot, a reverse shot with the camera angled slightly against the wall, just enough to maintain the position of the bottles in front of the room’s right-hand walls, one of the bottles explodes. So far so good; but in the next shot, Jeddy fires three shots in succession, followed by a reverse shot of three bottles exploding, one after the other.

Now, all three bottles cannot possibly have shattered after all three shots were fired. Obviously the correct way to represent this action would be to continue the shot-reverse shot rhythm showing how the first bottle was shattered. (So evident is this that Kuleshov’s editing here, despite the simplicity of the event, is actually more jarring than that of filmmakers who manipulate this convention, such as Sam Peckinpah conflating of two different times and spaces in the opening credits of Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid.

Now, if this were an Eisenstein film, we would say that Kuleshov was expanding time by repeating the same action from multiple perspectives, captivating and manipulating his audience by suspending us in the moment. But given Kuleshov’s otherwise invisible hand, and the early date of the film, we would characterize this as a mistake.

But a different shot-reverse shot pattern would hardly have been any more literal: given the speed at which bullets travel, the proper way to maintain the spatial, temporal and causal relations between shot and target, as seen in reality, would be in an over-the-shoulder or pov shot, as in any number of YouTube clips. Kuleshov’s error here, if we can call it that, has to do with the fact that film grammar had not yet developed this consensus.

It’s at the moments when agreement between film and audience break down, that we see how collaborative the relationship is. In Mr. West, Kuleshov includes a couple sequences which work as variations on his editing experiments. Mr. West receives two tours of Moscow, first from the swindlers and then from the authorities, offering two very different pictures of the Soviet experiment. In the first tour, close-ups of Mr. West looking offscreen alternate with insert close-ups of dilapidated buildings which Pudovkin’s identifies sadly, via dialogue intertitles, as former landmarks such as the Bolshoi Theatre; in the second tour, the shot pattern is repeated, but with inserts of the actual buildings, described triumphantly by an agent of the state.

The implied p.o.v. shots, of course, confirm the conclusions about space and inference suggested by the White House exercise. But as for Kuleshov’s most famous effect, the link is less immediately clear: Podobed’s very actorly expressions themselves underline the emotions also implied structurally (consistent, as we have discussed, with Soviet theories of montage in practice). What both tours do, though, is show how units of information, juxtaposed together, spin a narrative. As viewers, we connect the shots of buildings, the guide’s explanations, and Mr. West’s reactions; for Mr. West, the juxtaposition is of the name of a famous Moscow building, with either a bombed-out husk or a modern miracle. Like someone watching the clip of Mosjoukine or Jimmy Stewart, Mr. West combines the information he’s fed, and draws appropriate conclusions. This is beautiful propaganda filmmaking, because it’s also a beautiful demonstration of how both propaganda and filmmaking work.

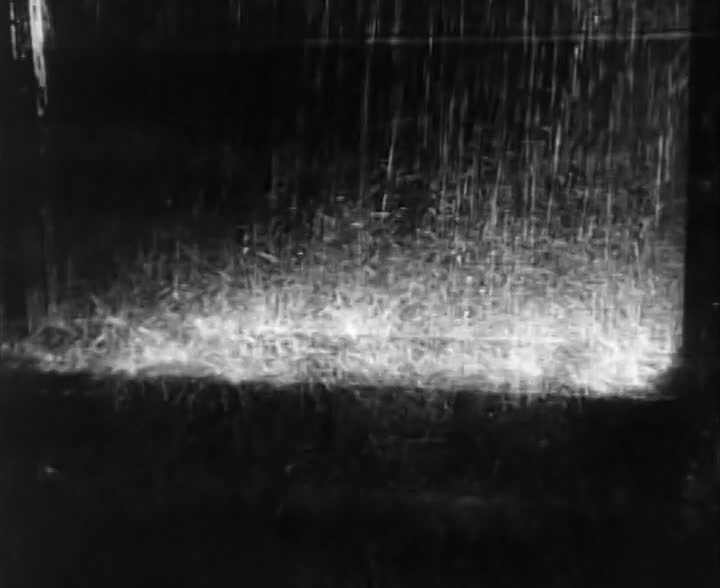

Obviously intertitles in silent films, like dialogue in sound films, can anchor meanings which might still be potentially diffuse, often to the point of redundancy—hence his use of them in Mr. West’s tours. But I want to end on a beautiful moment in By the Law, in which Kuleshov comes closest to the oversimplified “pure cinema” which has often been attributed to him. At one point in the crosscut burial and attempted escape sequence, the killer, struggling to get free, begins screaming. Kuleshov cuts between him and the open door of the shack, open as the wind and rain batter the threshold.

Presumably, though we’re not told what he’s saying, he’s yelling at his offscreen captors. But as Kuleshov cuts back and forth between the man and the storm, we make meaning from what we’re given, as Kuleshov recognized, and see a sad, angry, bound man, crying out against a raging storm.