Filmmakers Mark and Jay Duplass first hit the national radar with their Sundance hit The Puffy Chair in 2005. The story was small in scope and scale, boasting a handful of cast members, half of them Duplasses. Mark Duplass wrote and starred and Jay Duplass directed—the climax of the film (about a son bringing his dad a recliner like the one they had growing up) features both Mom and Pop Duplass doling out gentle wisdom. True to the family spirit, The Puffy Chair is a comedy of minor frustrations and gentle oppression, about educated twentysomethings who still don’t qualify as “grown ups.” The film shared a sentiment with other Sundance and SXSW alumni Andrew Bujalski (Funny Ha Ha, Mutual Appreciation) and Joe Swanberg (LOL, Kissing on the Mouth), so were lumped together, later to be dubbed ‘mumblecore’ as a comment on their characters’ difficulties with initiative. Though the term was coined by a soundman, it refers to the sort of slouching, navel gazing “seekers” who don’t declare their intentions so much as shuffle around them. The sound of their shuffling is consistently clean.

The unofficial movement of non-joiners would, ironically, grow in membership, and its intimate, prevalent ethos was critically heralded as the voice of a generation, the expression of an American condition. Each ‘mumblecore’ director had a thing: Swanberg favored frank portrayals of sex; Lynn Shelton (Humpday) lampooned masculine ambivalence; Frank V. Ross (Hohokam) linked stunted manhood to the new “working class.” (This is less a list than a tasting menu.)

What set the Duplasses apart was not their comedic sense—most of the mumblecore makers are out for laughs—it’s that the Duplasses have a unique accessibility. Maybe John of their 2003 short This Is John (2003) doesn’t know why recording his answering machine message drives him to tears, but you will. It’s a mundane taskmaster he wrestles to the ground, as if it’s the villain in an opera, gaslighter theatre style. This guy’s seen a lot of movies. John may make you cringe in embarrassment, but you’ll understand what he’s going through. If you’re one to yell at the screen, Super Bowl style, you might here. Perhaps it was a goal: the Duplasses love their competitive sports.

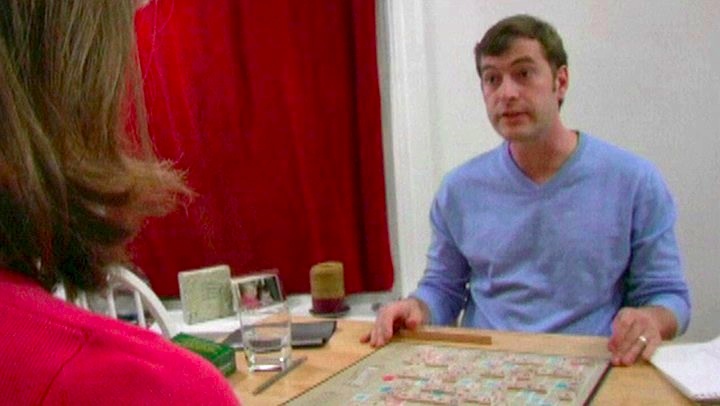

Their earliest movies proudly demonstrate family support. Scrapple (2004), like The Puffy Chair, features Mark Duplass against his real-life wife, Katie Aselton, playing well-heeled marrieds who take their board games too seriously. Even if these characters aren’t unmoored twentysomethings (though pearls and sweater sets don’t prove they’re not) Scrapple is a tidy example of the mumblecore context: everyone’s kept cool long enough for trivial offenses to feel like cracks in a damn. It’d be Kitchen Sink Comedy if we ever saw the events that led to the pile up. The result isn’t identification—it’s empathy, which is part of what cues us to laugh and cringe and shake our heads. It’s hard to identify with someone who spits on her husband over a Scrabble board—sure he’s a bad winner, but it’s not like we see him steal a “z.”

The year of The Puffy Chair the Duplasses made The Intervention (2005), a fifteen-minute short that pretends to be about a group of friends trying to corner one of their number in a lie: maybe he bought that autographed Bill Parcells memorabilia, maybe he met Parcells and handed him a Sharpie…. The real intervention has nothing to do with any of that, of course. But it might prove that if the stage is set for an intervention, you’ll have one, even if you have to invent it along the way.

With the successes of 2005, the brothers had a shot to team up with their mumblecore brethren and the result was Baghead (2008), a comic thriller about the contradictions of the indieverse. Baghead reveals the group’s resolute ambitions, while it pokes fun at the proposition of playing make-believe for a living. It had a select theatrical run and continues a happy life on the Internet, buoyed by its still ascending stars (Mark Duplass and Greta Gerwig, especially). They also peppered in Steve Zissis, the main character in The Intervention and the family comedy they made about psychic regressing: The Do-Deca-Pentathlon (2012).

Though it didn’t see theaters (Red Flag Releasing) until 2012, DoDeca feels like a page out of the brothers’ lives. Zissis is turning forty and his younger brother has come out of the woodwork for the party. The family man and the cardshark rekindle an old rivalry: a faux-Olympic competition of twenty five events (holding your breath under water, sprinting to the stop sign, staring contest) that define their filial common ground. It’s also how one forty-year-old turns fifteen again, while his tween son watches. In an unpublished interview I conducted with Jay Duplass in 2012, he said “there comes a point in your adult family life when you can’t strive to be the best you can be because you have a family.” Adulthood, in this case, carries with it some oddly Faustian bargains.

Sibling rivalries are ever-present in the Duplass canon, but aren’t limited to blood relatives. Cyrus (2010), which keyed the brothers’ rise to national prominence, had an all-star cast and repackaged the traditional rivalry to a battle between a son (Jonah Hill) and his mother’s would-be suitor (John C. Reilly). Despite being perfectly eligible, Cyrus’ mom (Marisa Tomei) has stunted her romantic life for fear of making her son uncomfortable; the smarmy affection he doles out may be compensating for what he knows she loses in that bargain. That said, he’s not interested in moving out and doesn’t care what anyone thinks. But it wouldn’t be a Duplass film if it didn’t have copious crash zooms and at least one opportunity for a grown man to act like a playground peon. Inside every Duplass comedy is a metaphorical jungle gym and two “men” clamoring for dominion.

Jeff, Who Lives at Home (2011) contains the hallmark family dynamics, but the Duplasses settle in on one hero. Jeff (Jason Segel) is a seeker, a wannabe mystic, a romantic, the king of his mother’s basement. He’s certain he’s got some purpose on earth but a series of middling dramas pertaining to his brother’s marriage get in the way. Jeff doesn’t completely lack maturity, indeed he may be the most considerate and attentive guy in the film, but he struggles for motivation and he’s emblematic of the kind of vulnerability that makes these manchildren endearing. You don’t need to identify to want more for the guy and the Duplasses want him to be like Lancelot in basketball shorts. Happily, the takeaway isn’t a romance, and no job sweeps Jeff into the workforce to live the structured life that in movie parlance means stability, comfort, happiness. Yet, what Jeff and his brother gain through their petty arbitrations and grudge matches is a filial romance that’s stable and comforting—a happy acceptance of the reality that family is forever.