In his career’s final decade, Rock Hudson, not unlike a number of aging but venerated studio titans of his generation, found steady work on the small screen in episodic dramas. No longer did one have to leave home and pay the price of admission to see the 6’4 actor wax genteel. In the heyday of primetime television, Mr. Hudson approached the viewer, sauntering into one’s parlor via radio waves in McMillan & Wife, The Devlin Connection, and Dynasty. This was his curtain call, and it was hardly celebratory.

To this day, Hudson’s legacy remains nearly as closeted as he was in life. This is not solely due to the synonymity of his name with HIV/AIDS, but by the plague of misinformation that accompanied the virus in the 1980s. As a flurry of tabloids broke the news that actor was positive and discreetly seeking treatment in Paris, Dynasty viewers panicked that Hudson had selfishly compromised his co-star Linda Evans’ health by going through with an on-screen kiss. This isolated spectacle threatened to become a larger part of cinema history than Hudson himself.

Resurfacing fourteen years after Hudson’s death, a lost interview (conducted during the kiss’ shoot on Christmas Eve 1984) offers insight into what made Hudson tick: he boasted both gumption and an unusual strain of masculine vulnerability; a pensiveness, perhaps partially mastered through his own life experiences. Hudson joined the Dynasty cast with the unwavering attitude of a film star. He was determined to make meaning — and provoke complex feelings — in a genre intent on limiting it: the soap opera. “I believe in working hard and I believe in doing the best I can. If you get lazy or tired of something, then you don’t do your best work,” he told Entertainment Tonight’s Lisa Gibbons. When Gibbons asked the 59 year-old if he desired to sign on for more than six episodes, he balked. For Hudson, quantity did not make quality. “I don’t like being on every week,” he answered. “Scenes will become so unimportant that it becomes like sawdust.”

Hudson’s sexuality is often, myopically enough, only seen as a death sentence. In hindsight, it serves to make his performances, particularly the three romantic comedies alongside Doris Day and in ten films directed by Douglas Sirk, all the more enigmatic. In the 1992 essay documentary Rock Hudson’s Home Movies, director Mark Rappaport guides the viewer through the subtext of Hudson’s filmography: chaste exchanges with female co-stars, lingering glances shared with their male counterparts, and the medical horror scenes that cryptically allude to his death. “I had learned a great deal about the illusory nature of the screen image. When I died of AIDS in 1985, everyone was so shocked that the lesser shock that I was gay was more easily absorbed,” an actor loosely resembling Rock Hudson says as these now-damning clips roll.

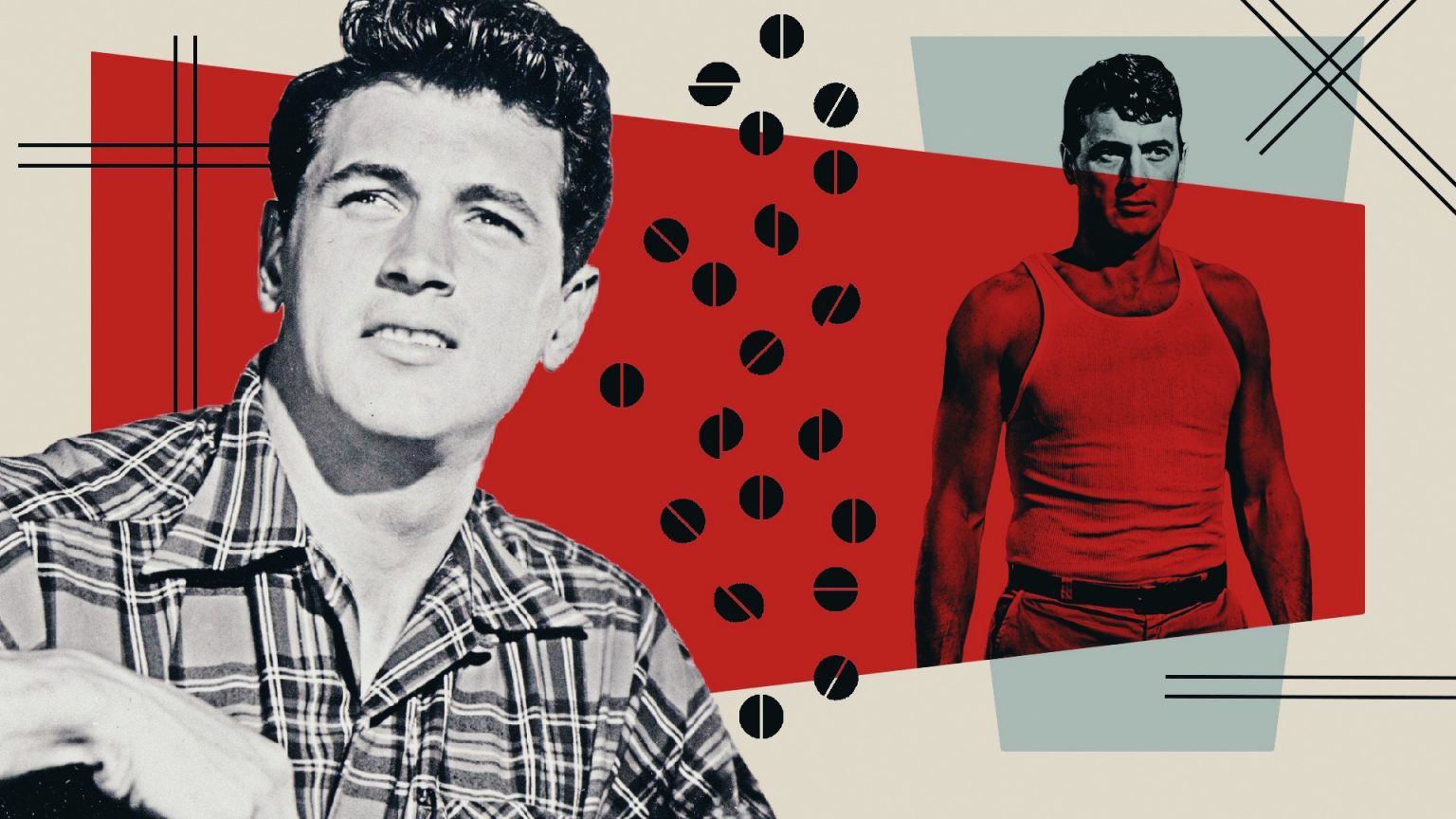

Hudson’s sexuality also afforded him opportunity and community. He regularly dined with actor George Nader and his life-long companion, Mark Miller and was introduced to Henry Wilson, the man who would become his agent through a lover in the late 1940s. Wilson quickly got to work on cultivating the aspiring actor’s tall, dark, and handsome image. A name change, as with his client Tab Hunter (formerly Art Kelm), was of highest priority. Wilson’s actors included ex-military boys boasting complexions unmarred by shrapnel and uncontested masculinity; more often than not, they played facsimiles of themselves on-screen. Yet when the movie magazine Confidential threatened to out Hudson, Wilson offered them dirt on Tab’s proclivities instead. Hudson’s burgeoning portrait of cinematic masculinity couldn’t be tarnished.

Hollywood is exceptionally patient with nascent male actors who make up for limited range with good looks. And “raw talent” is a deceptive phrase to apply to a performer. Initially, everyone is “raw”— and the only “talent” is the publicist who will inevitably spin the narrative of a star being born. Tom Cruise, Matthew McConaughey, and Channing Tatum are today’s beneficiaries of the system that initially gave Rock Hudson a shot. A University of Southern California theater program reject, Hudson didn’t really set foot in a proper acting class until he landed a contract at Universal. Even then, it took him a while to get up to speed. The earliest films are forgettable, so much that Hudson went uncredited in the first of them: Raoul Walsh’s Fighter Squadron, a macho postwar aviation flick. “He was absolutely petrified,” Fighter actor Jack Larson once recalled. “He’d stumble, he’d gulp, he’d forget the lines, he wouldn’t come in. It was an unbelievable situation. Finally, they got something, but the scene was cut out of the film.”

Yet he was a fast learner — and a humble one. “The most dangerous thing for an actor is to refuse to listen to anyone else, to feel you know more than anybody,” he famously said. By the mid-1950s, Hudson had found his celluloid legs in Sirk’s Technicolor films, beginning with Magnificent Obsession and All That Heaven Allows. Each contends with flawed women who fall for all too available men who, as played by Hudson, exude a mix of stoicism and softness that only melodrama is poised to legitimize.

Watch Now: The award-winning documentary, Rock Hudson’s Home Movies, here on Fandor.