What’s with Paul Henreid anyway? What a strange career. He was one of the few middle-European male stars to come to America during the war who did not wind up playing Nazi officers, although he did play one in the British Night Train to Munich (1940), which served as his calling card to Hollywood.

From the very beginning of his Hollywood career, in Now, Voyager (1942), he played the world-weary European of indeterminate accent who was somewhere between a lounge lizard and a sensitive artiste type. Just as his accent was indeterminate, so was his past. He’s from somewhere “over there.” In the interests of protecting the innocent, no details, please. His past was probably very ugly as was, no doubt, the war he survived—don’t even dream of asking how—so the less we know about it the better. When he comes to America in Deception (1946), all we know is that he was stuck “over there” and it was “bad, very bad.” Tell us every little thing about the love triangle between Henreid, Bette Davis and Claude Rains, just don’t bore us to death with grim stories about suffering and war in foreign parts. His most politically charged comment is that he, a classical musician, “wouldn’t play for them.” Who “them” refers to is not explained, but we can guess.

In Casablanca (1942), he is a resistance fighter in absentia, if such a thing is possible. He refers to himself as being privileged to be “the Leader of a Great Movement” despite the fact that, usually, resistance fighters can’t claim such glory for themselves until the occupier is defeated. Calling himself that also suggests that the resistance was a well-organized force guided by strong leaders, with back-up from weak-willed followers. Again, as few details as possible. He delicately and maybe a little coyly asks Ingrid Bergman, “When I was in the concentration camp, were you lonely in Paris?” This is as political as it gets—brushing aside the implausibility of any political prisoner being released from concentration camps.*

He was generically handsome, sophisticated and had a pleasant, non-grating accent—the difference between German refugees, like Conrad Veidt, and Austrian refugees, like Henried and Franz Lederer, who could also play Frenchmen in a pinch, as they sometimes did. Henreid obviously was not one of those refugees who had to hurriedly throw a few items in a suitcase and leave on the next train. He has an extensive wardrobe of neatly pressed, well-tailored clothes, including several summer suits (!), not to mention an equally well-outfitted wife, Bergman. He has an unexplained, charmingly placed but not disfiguring scar on his forehead and a dashing streak of gray hair, which suggests that at some point he might have suffered a bit, but on him it looks good. He is central casting’s idea of the kind of refugee you wouldn’t mind inviting into your living room. He’s not always complaining about his destroyed life, his devastated country, and the loved ones he’s lost. When Henreid is not playing elegant, artistic refugees, he is playing artistic types suffering from bouts of great sensitivity.

But something happens to Paul Henreid after the war is over. Of course, something happened to everyone in Hollywood after the war was over. Warner Brothers was divesting itself of, often by mutual agreement, and/or fighting with all of its big stars (Bette Davis, Humphrey Bogart, Joan Crawford, Errol Flynn, John Garfield, James Cagney), as well as its smaller, non-star stars, like Claude Rains, Ida Lupino, Ann Sheridan, Ronald Reagan and its stable of below-the-title character actors like Sydney Greenstreet, Jack Carson, Peter Lorre, Zachary Scott. The onslaught of television, anti-trust suits, the forced divestments of the studios owning their own movie theaters and the blacklist changed the way that movies were being made and were going to be made. Between 1947 and 1950, almost all of the contract players of the ’30s and ’40s who put such a singular stamp on Warner’s films—indeed, suggesting that, along with the same handful of reliable directors, it was an extended stock company making one very long picture Warner Brothers picture, always chock full of friendly and familiar faces—were gone. Non-stars but reliable staples like Paul Henreid were not going to have an easy time of it. But maybe this is what frees Paul Henreid to discover his true self—the darker side of Paul Henreid.

His first non-Warners movie, Song of Love (1947) for MGM, in which he plays Robert Schumann, was a partial, unexplored trip into uncharted territories. Schumann’s suicide attempts, depressions and his final and permanent incarceration in a mental institution do not have a very large role in the sentimental, culture-mongering bio-pic but it gives a hint of what lay in store for Henreid. He is taking his first step.

In 1948, he produces, and stars in, a very low-budget movie The Scar, directed by Steve Sekely. In it, Henreid, a small-time chiseler, assumes the identity of a well-known psychiatrist to whom he bears an uncanny resemblance. He should. He plays both parts. The only difference between the two is, no, not the mittel-Europeische accent that they both have, but that the psychiatrist has a scar on one side of his face. Johnny, the bad Henreid, in order to impersonate Victor, the not-much-better Henreid, before he kills him, has to carve a similar scar into the side of his face. Once he achieves Victor-hood, things don’t get a whole lot better. Victor, it seems, is an inveterate gambler who owes thousands of dollars. Johnny tries to talk the mob out of killing him, trying, in vain, to prove that he is not actually Victor.

He has an unexplained, charmingly placed but not disfiguring scar on his forehead and a dashing streak of gray hair, which suggests that at some point he might have suffered a bit, but on him it looks good. He is central casting’s idea of the kind of refugee you wouldn’t mind inviting into your living room.

It’s a beautifully shot little movie, by the great John Alton, king of low-budget noir. To further enhance its noir credentials, it even has a very muted Joan Bennett in it. It’s the usual identity-theft dilemma. You steal someone else’s life, usually someone much richer than you are and then discover, too late, that their problems are worse than your old ones seemed to be. The impostor is hoisted on the petard of the unforeseen complications he inherited from the person he or she is impersonating. Aside from the juicy double role it offered the star, the good-twin/bad-twin dichotomy (i.e., Bette Davis in A Stolen Life, Olivia de Havilland in Dark Mirror), became a reliable sub-genre, owing much to the doppelgänger German Romantic literature that swept through Western literature in the 1800s—the most successful and most lasting variants on the theme being Dostoyevsky’s The Double, Gogol’s The Nose, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. It was a relatively new sub-genre for films partly as a result of the technical possibility of having an actor play in scenes with his “double.” And the war itself gave people an interesting, seemingly new reason to contemplate once again the darker, unexamined sides of the human psyche. This is an arena in which Henreid made a niche for himself.

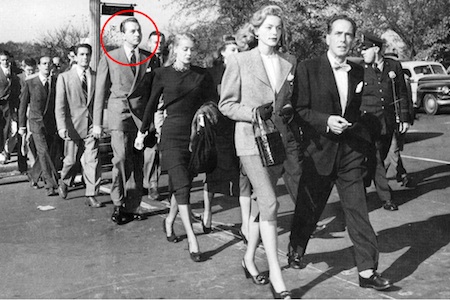

He is no longer sought after as the romantic lead. Age has something to do with it. But he is also blacklisted, which has a lot more to do with it. A famous photograph of a contingent of Hollywood actors in Washington (including Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Danny Kaye, Richard Conte, and June Havoc) protesting the HUAC hearings investigating allegedly Communist-controlled Hollywood films made him a very prominent target. He is still more evil in William Dieterle’s 1949 Rope of Sand. He plays a sadistic, brutal police officer responsible for the security of South African diamond mines. Now he’s really starting to connect to his darker self. The relish with which he tortures and humiliates Burt Lancaster makes him, once and for all, unsuitable for romantic leads. Basically, he is playing the Nazi he was never permitted or invited or allowed to play in his Warner Brothers days.

It’s the usual identity-theft dilemma. You steal someone else’s life, usually someone much richer than you are and then discover, too late, that their problems are worse than your old ones seemed to be.

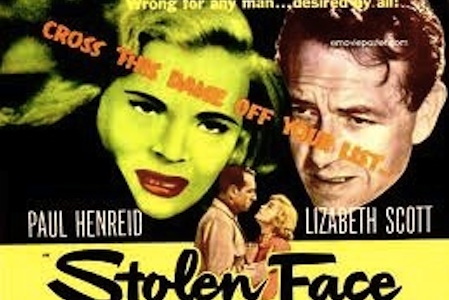

He stars in low-budget features and directs and produces as well. In 1952, Henreid stars in a low-budget British movie called Stolen Face, which could have served equally well as the title for The Scar, in which he plays a plastic surgeon. He does pro-bono plastic surgery on a hardened criminal whom he feels has resorted to crime as a result of her disfigured face. Having a brand new identity, he reasons, will give her a sense of her own self-worth and wean her away from her life of crime. But before the operation, he falls in love with Lizabeth Scott, a famous concert pianist. Even though she too loves him, she plans to go through with her long-planned wedding to her fiancé. When Henreid loses her for good, or so he thinks, he decides to give the convict Lizabeth’s face. No greater—or nuttier— tribute can a man offer the woman he loves. We are deep in Hitchcock-land here. After the successful operation, he decides to marry the woman who now looks exactly like the woman he loves, even though she is someone else. After all, he created her in the image of the woman he loves, so he should get to keep her, right? It turns out not to be such a good idea. She, the new Lizabeth Scott, with the cockney voice dubbed in from the pre-op English actress, is hopelessly addicted to a life of crime and, despite her new face, reverts to her old life. Meanwhile, the good Lizabeth Scott, she with the raspy voice of sandpaper rubbing tarnished silver, has come to her senses. She called off her wedding because she realizes it’s Henreid whom she really loves. Now there are two Lizabeth Scotts—the bad Lizabeth Scott, who won’t divorce Paul Henreid because he’s got money and social position and the good Lizabeth Scott, who wants to marry him. While the bad Lizabeth Scott and Henreid are arguing on a train, she accidentally falls off—to her death—leaving Henreid free to get back with the good Lizabeth Scott. The End. Just when it was getting interesting, too. The lack of imagination in how to more fully develop this ur-Vertigo theme prevents this movie from becoming more that just another stolen-identity entry, although it had the potential to be much more. But what it does reveal is that Paul Henreid is almost fatally attracted to this theme. It’s almost as if he has discovered a new part of himself: every good character has an evil double lurking out there, and vice-versa. After years of being corseted as Warner Brothers good lounge lizard (Zachary Scott was the bad lounge lizard) and unthreatening refugee roles, he can finally kick up his heels.

Perhaps the psychological turning point in Henreid’s career had been in the Carol Reed’s Night Train to Munich. We first see him in a concentration camp (yes, even in England in 1940, enough people new about concentration camps to include them in a film), being beaten for his defiance and insolence to Nazi officers. He makes a plan with Margaret Lockwood, also a prisoner, to escape and flee to safety in England. There she can make contact with her father, a Czech scientist, who is already in England. He was forced to flee because he has the secret formula that the Nazis desperately want. It turns out that Henreid (or von Hernreid as he is billed in the film) is really a high-ranking Nazi officer trying to discover the whereabouts of Lockwood’s father. His pretense of being a nice guy was just a ruse to lead her to and kidnap the scientist father. Maybe all the confusion starts here. Henreid/von Hernreid is very sympathetic as the anti-Nazi. If it is genuinely disappointing for the viewer to discover that he really is a Nazi, just imagine how Margaret Lockwood must have felt! Rex Harrison, the lead actor, also lives by impersonation. He plays a British Service agent who pretends to be a Nazi, but since he is basically a good guy, winds up getting the girl. That always makes a big difference.

Perhaps the mid-career shift by Henreid is occasioned by what is known as “survivor guilt.” He very possibly feels guilty that other refugees like Conrad Veidt and Francis Lederer, also leading men in Europe, who, once they escaped to Hollywood, are forced, ironically enough, as are other refugees, to portray the bad guys from whom they fled. All three were in a sense reduced to character roles in America, but Henreid was the luckiest of them, never playing tough guys, never playing Nazis, in Hollywood at least. We are so used to seeing him as the romantic second lead that when he does play a hardened criminal in The Scar, a movie that had an identity crisis of it’s own since it was also known alternately as Hollow Triumph, it’s almost laugh-inducing.

There is a real fissure in the Paul Henreid persona. He seems to feel he has to expiate himself for having played romantic roles during the war years and, after the war, starts playing tougher, uglier, more conflicted characters. The split is widened even further, compounded by his desire to direct.** After a few low-budget features, he starts directing episodic television. Even though he continues to act in movies from time to time, very likely to pay the rent, he directs almost non-stop until he retires. In fact, his list of credits as a director is much longer than this acting resume. He directs 28 episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, out of a total of 266 episodes, from 1957 through 1962—more that 10 percent of all the shows produced, second only to Robert Stevens, who directed a whopping 44 episodes and only slightly more than Herschel Daugherty (24). Hitchcock himself, in comparison, directed a piddling 17, but, during the same period, was making some of his greatest films, not to mention starring as the show’s host week after week.

The onslaught of television, anti-trust suits, the forced divestments of the studios owning their own movie theaters, and the blacklist changed the way that movies were being made and were going to be made. Between 1947 and 1950, almost all of the contract players of the ’30s and ’40s who put such a singular stamp on Warner’s films—indeed, suggesting that, along with the same handful of reliable directors, it was an extended stock company making one very long picture Warner Brothers picture, always chock full of friendly and familiar faces—were gone. Non-stars but reliable staples like Paul Henreid were not going to have an easy time of it. But maybe this is what frees Paul Henreid to discover his true self—the darker side of Paul Henreid.

We don’t think of Hitchcock as being involved in politics, despite his fear and even horror of authority figures, and his distaste for American foreign policy makers (part of America’s way of waging war involves nonchalantly and gently pressuring women as elegant as Ingrid Bergman and Eva Maria Saint into sleeping with the enemy to discover their secrets), yet he gave Norman Lloyd, a blacklisted actor, who had appeared in both Saboteur and Spellbound, a permanent home, producing and then directing, for Alfred Hitchcock Presents and also provided a safe harbor for Paul Henreid, clearly one of his favorite house directors.

Cut to the ’60s. Almost 20 years later, Henreid revisits the dichotomies that have shaped his artistic life. Once more he plays the suave European resisting the German occupation. And he will also have one last fling, as one of the foremost proponents of the stolen-identity, Manichean personality-split theme. The most elaborate and expensive flowering of this aspect of his work is in Dead Ringer (1964) in which Bette Davis, once again a star, this time of horror movies as a result of her unexpected success in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), gets to reprise her Stolen Life roles as another set of twins on the old Warner Brothers lot. Now, Voyager and Deception were made a lifetime ago. But Henreid and Davis are back together again, not as lovers this time, with Claude Rains lurking somewhere in the background, but as director and star. The evil twin stole the good twin’s boyfriend many years ago and married him. He subsequently became rich and died, leaving the evil twin all of his money. We never get to see the dead husband, who, for all we know, might well have been Paul Henreid. Let’s pretend he was, it’ll make it more interesting. The good twin, actually, is not so good and murders the evil twin, who is not so bad, and takes her place. Now she has the money but not the man she loved years ago or the life that was owed her. She finds out that the twin she murdered and her lover, Peter Lawford, of all people, who is 15 years her junior, have killed her husband for his money. When faced with Lawford’s blackmailing schemes, she realizes she also has to kill him, too. It’s a plot worthy of The Scar made 16 years earlier or Stolen Face made 12 years earlier, it’s that old-fashioned. Except that those were both very low-budget films with not enough resources to more fully explore their intrinsically more interesting plot complications. The most interesting thing about Dead Ringer is that Henreid and Davis are back together again on the Warner’s lot, with Ernest Haller, who was a Warner’s contract cinematographer for two more than decades, back with them. He shot 16 films with Davis, starting in 1932, including some of her best-known movies— Dangerous, Jezebel, Dark Victory, Mr. Skeffington, Deception (with Henreid) and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? He even shot an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents directed by Henreid and starring Davis, “Out There- Darkness,” in 1959, probably, one guesses, as a favor to Davis. He also shot an episode of the one-hour dramatic show, Suspicion, which also starred Davis a year earlier. It’s more fun imagining what the three of them talked about at lunch than it is to watch the movie.

Meanwhile, the other side of Henreid’s professional career as an actor had been revisited again in 1962. Once more he is the sophisticated, Nazi resister, French this time, in Minnelli’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. This time he is not only aware of his wife’s betrayal with another man, he knowingly sends the other man, Glenn Ford, on a suicide mission behind enemy lines. This is a far cry from everyone’s noble, sentimental sacrifices in Casablanca. This time he is tortured, and looks it. This time, despite Minnelli’s lush art direction, it looks like the war isn’t a lot of fun. This time Paul Lucas, who played a Nazi refugee in Warner Brother’s Watch on the Rhine (1943), a role Henreid might have played, is a Nazi general. This is MGM’s Cinemascope revenge on Warner Brothers’ wartime diffidence, twenty years earlier. Despite color and Cinemascope, everybody dies. No happy endings in the new Hollywood.

So with Four Horsemen and Dead Ringer, Henreid’s double-pronged career(s) comes full circle. We know that actors don’t make up their own lines, that they were at the mercy of their studios and their agents and the material that is available to them, and that their choices, for the most part, were determined by forces beyond their control. And yet, and yet, if an acting career can be summed up, as directing careers often are, by the auteur theory—suggesting that there are common and repeated themes appearing and re-appearing in different guises throughout the artist’s work, let us acknowledge Paul Henreid as an actor who has made, if not deliberate choices, let us say, unconscious choices, defining himself through the roles he plays, thereby creating for himself a special category—actor-as-auteur.

_______________________________________________________

* More World War II, According to the Brothers Warner. In Mr. Skeffington (1943), Claude Rains plays a Jew. Don’t go out to the popcorn stand because there’s only one fleeting reference to that effect in the whole two-and-a-half-hour movie. If you miss that, you’ll never know what’s going on. He is, just incidentally, sent to a concentration camp and comes back hearty and hale, with no horror stories to tell. The bad news is he is blind—not as a result of torture or disease, but because his blindness is useful to the plot. He cannot see that Bette Davis has grown old. His blindness allows him to imagine her as eternally beautiful.

** He is said to have come up with the creepy, much-imitated sexual metaphor in Now, Voyager, of lighting two cigarettes at one time and handing the other lit cigarette to Davis. Perhaps he was encouraged by the success of his first flirtation with directing.