For a brief period in the mid fifties, Los Angeles’ prime time TV audiences could tune in and watch a lady in black emerge from low-fidelity shadows to introduce a movie. The First Empress of the Night, Vampira (Maila Nurmi) entered the screen with a corset so tight she recalled a busty classroom skeleton. Down a misty corridor you could see her, hear her shriek, and then she’d purr, “Screaming relaxes me so.”

Vampira’s performances were wrapped with cheap but loving care in all the trappings of dimestore Hallows’ Eve. Candelabra, black curtains and velvet chaise suggested decaying wealth and the depravity of previous owners. Vampira introduced low-rent horror, but she packaged these clichés as pleasure, decadence, a send-up of the “left hand path.” It was a playful charade, G-rated for those too young to grasp her innuendo, though the (sexually) uninitiated felt her allure nonetheless. Those in the know could laugh as she used otherworldliness to justify earthly pleasures.

Somewhere in the fifties, however, Satan took a holiday. It’s not Vampira’s fault, cinema just began to prefer his influence to his presence. Decades earlier magician George Méliès portrayed him impish with horns and tail (hardly a sexual predator); Paul Wegener made him the reflection of The Student of Prague; F.W. Murnau transformed him into a behemoth shadowbringer with a cloaked body bigger than a city (Faust), but after the 1960s Beelzebub is not so literal. Oh he’s had curtain calls, played by Gabriel Byrne, Robert De Niro or Telly Savalas, but he’s mostly emeritus. The trashy cinema that likes him best likes him because he’s become the ruse; Woman is no longer the pathway to The Devil, she’s his scapegoat, and sex is proof he’s “real.” Imaginary Satan is like Santa for dirty deeds. What follows is an inventory of underworldly influences, much of which is to be taken under advisement by mature audiences only.

1. Exorcism (a.k.a. Demoniac) (1974)

The story of Exorcism (aka Demoniac) shape shifts with each retelling: In some synopses a witch has possessed multiple women and only the Doctor (played by Spanish writer/director Jess Franco) can excise their demons. In others Franco plays a defrocked priest turned serial killer, expunging faux-satanic performers from the promisingly arty middle classes. In either it’s Franco’s primary co-conspirator, Lina Romay—guileless product of her generation and smirking play-victim—that the camera likes best.

2. Mark of the Devil (1970)

To find the Mark of the Devil on prospective witches, medieval witch hunters tied their naked defendants to racks and stretched them, clamped their mouths open and cut their tongues out. Like imaginary retribution for any girl who ever said “no” these tortures all invert some sex act. Rape is common, violent and as casually criminal as redemptive and exculpatory. Provincial witch hunters rule their towns, trading sex for survival and proving the hottest wenches are Satan’s mistresses through public torture. Young Udo Kier is an idealistic apprentice witch hunter and the god of pretty boys, offering here the most confusing bit of titillation to arise from the plight of an idealist. When a local girl is wrongly imprisoned his judgments are called into question. Is his business corrupt? Absolutely. Was it ever pure? What is?

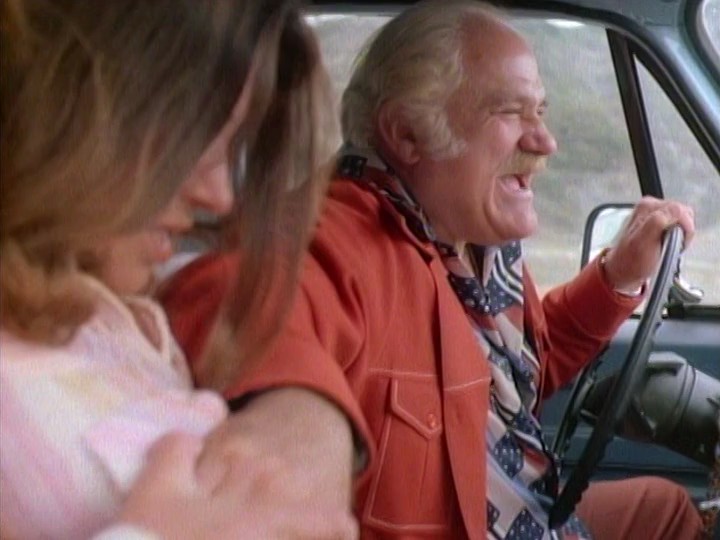

3. Satan’s Cheerleaders (1977)

In Satan’s Cheerleaders the high school janitor has grown so tortured by the bikini-ready cheer squad (the giggling! The messes!) he hijacks the van to the playoffs and, with the help of a hungry John Carradine, redirects it towards a town of wet-brains, mightily lorded over by a less than capable Sheriff (John Ireland) and his wife (Yvonne DeCarlo). In between the thin reasons cheerleaders shed their tops (never a bra), run through open fields (again, no bras) or land Bridget Jones’ style on the camera, a bumbling Sydney Chaplin (Charlie’s son, playing a monk) begs for the Sheriff’s clemency while the Janitor is rebuked because he wants too great a stake in the town’s offering to Satan (the girls!). Some read the conclusion as an admission that the heroine was a witch, others that the sex she was having at school somehow gave her a mainline communiqué to the Dark Lord—either way, the audience looks on like the janitor, annoyed by the giggling, stunned by the bouncing.

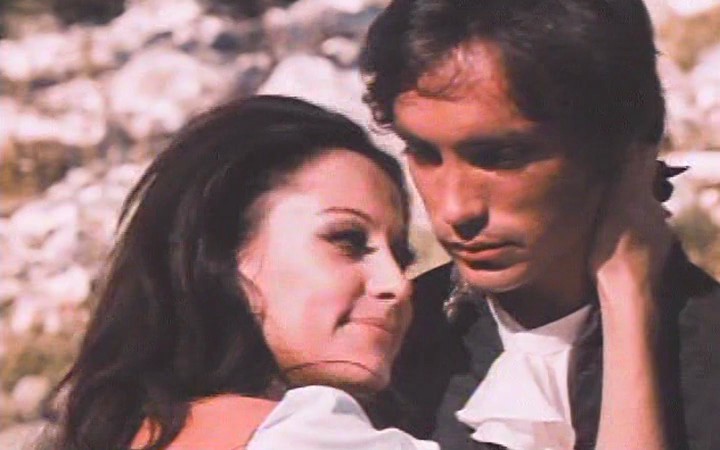

4. Black Sunday (a.k.a. Mask of Satan) (1960)

Mario Bava seemed to signal a golden age of occult cinema with Black Sunday, and the evocative black-and-white cinematography repeatedly suggested that Mephistopheles is not a body but an embodiment of the unknown. A bonfire casts harsh shadows as Asa (Barbara Steele in a brilliant double role) is burned at the stake, screaming her devotion to Lucifer as the fires licks her through a torn dress. A higher-than-thou puritan nails a beastly mask to her face; her final howl is a consummation. When a man of science carelessly revives her, she seeks to undo the lineage that damned her, culminating in the possession of her great niece Katja (Steele again, in the White Swan role). These women could indeed be gateways to The Devil, but from our view they seem like his floodgates. Bava’s first major picture, Black Sunday takes place in ancient boudoir, with Katja roaming in her nightgown and ancestors hiding voyeuristically behind curtains, angling to defile, relieve her of innocence, enter and capture so she might live out a debt to Satan. Sounds like deflowering to me.

5. Lisa and the Devil (1973)

Another version of Lisa and the Devil exists under the title The House of Exorcism. In both, Lisa (Elke Summer) visits an ancient city and gets separated from her tour group. A kindly chauffeur invites her to stay at a Villa owned by a bent old family. They act as if they’ve never experienced society but live in a state of perpetual dinner party. Lisa will evade the family’s curse and be a helper to dinner guests as they casually suffer or die, but it’s her fate to face The Beast, the puppet master and domestic servant who delights in the fact old money is slow poison. He will rule this day, and she will see him most clearly on her back.

6. Dawn of an Evil Millennium (1988)

Unlike its sexy brethren, Damon Packard‘s Dawn of an Evil Millennium blames a demon for violence instead of sex. This eighties experiment builds chaotic energy following a fiend’s rampage through the Los Angeles streets. He finds consolation in a vintage muscle car, his rumbling voice over occasionally bleeding into the throaty grrr of the engine. But the aggression can’t be sublimated and the fake blood and cheap plastic fangs are following this devil to another calling…recruitment.

7. Satan’s Slave (1976)

Catherine is Satan’s Slave, the descendant of a long dead witch, buried in a forest that’s “protected because of what happened there.” Plagued by premonitions she’s been burned at the stake (she is a dead ringer for the witch) she can’t explain the force that overcomes her as she stays in her adopted uncle’s castle. “It’s all like a dream,” a sordid, lusty dream. Her cousin has a violent streak—confusing sex and murder (or confusing knives and penises, it’s not clear) and every romantic entanglement ends with a butchering. Indeed all nudity in Satan’s Slave involves knife wielding. The agenda is necromancy: use the nubile Catherine as a proxy to revive the dead but powerful ancestress, and as any pushy man will tell you, repossession makes sense because women are interchangeable.

8. The City of the Dead (1960)

City of the Dead is essentially a British Dunwich horror, comically reset in Massachusetts and it’s the sort of low-budget production film students hold up as a model of efficiency. A beautiful student is coaxed by her professor (Christopher Lee) to visit a misty small town to research its historic witch trials. The town, mostly composed of graveyard, would be charming if the daylight ever graced its buildings. The innkeeper is a manipulative sort, a sharp taskmaster to her mute servant-girl, but in the throes of ritual she seems exuberant, rapturous, in thrall. The ever-restrained Brits likely thought it gauche to explain the ecstasy much further, but whatever’s in that ritual has kept young for four centuries. Blame the endorphins.