Of the great many essays, op-eds and thinkpieces in which the name David Foster Wallace is reverently invoked—and at this point, I expect, there are too many to read even if you dedicated your life to the task exclusively—the most reliably irritating are those which take the death of irony as their subject. These laborious tracts always proceed from the same spirit of false discovery, as if the author, having just struggled through a trade paperback of A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again for the first time, had stumbled upon a trove of revelatory insight heretofore absent from contemporary discourse. I understand the impulse: Wallace is the sort of writer whose work encourages a kind of shared enthusiasm, a literary a rock star whose vigor and virtuosity impresses itself upon you indelibly. You can always spot a new DFW fan: check out the new found loquacity, the po-faced sense of wonder. Keep an eye out for footnotes.

This influence, however much you admire the source, has resulted in a lot of bad writing—in literature, certainly, but in cultural criticism especially. “E Unibus Pluram,” Wallace’s heady treatise against the deteriorating effects of television and irony on modern literature and one of his most widely cited pieces, was published in the Contemporary Review of Fiction exactly twenty years ago this summer, and yet two decades on it continues to be regarded by new readers as if its ideas were just now emerging for the first time, ready to galvanize the irony-dead masses and correct the course of popular culture as we know it. The essay’s final lines have proven to be an apparently inexhaustible source of hope and inspiration for those wearied to creative impotence by the posturing of modern art: “The new rebels might be artists willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists . . .” I suppose we’re meant to read these words and be provoked and invigorated, stirred to some sentimental action. We’re meant to summarily ditch irony and throw away the TV. Go outside. Buy a Dave Eggers book.

It probably comes as a bit of a surprise to these kinds of Wallace disciples that irony survives their impassioned monographs against it. Indeed, the stubborn thing has persisted despite a genuine movement worked up and rallied around in opposition—a buzzy thing they call ‘New Sincerity’, whose proponents pride themselves on adopting an earnest approach to television, film, and literature, rejecting the toxic influence of cynicism in favor of all things light and endearing. This lot fancies themselves the rebels imagined by Wallace in ’93, out there risking their reputations at the hands of the literary world’s yawning, winking masses, and as a whole they’ve done quite well for themselves. Such artists endeavor to return to a state of saccharine bliss, engaging the world with wide-eyed zeal.

This doesn’t strike me as an especially sophisticated response to the flatness or superficiality of ironic posturing—in fact it’s little more than one veneer of falseness substituted for the more dominant one, no more or less inherently substantive and certainly no closer to a kind of artistic authenticity. Well, given what’s been exalted under the terms set out by Wallace—as when Stanley Fish, writing in the New York Times, praised last year’s film adaptation of Les Miserables by framing it as an ideal Wallacian antidote to our over-ironized times, easily the low point of the movement—I’m not sure deference to Wallace is even a preferable alternative to shrugging everything off with a postmodern wink. If that’s what passes for rebellious and bold we ought to rethink the usefulness of the approach—after all, irony may be cynical, but at least it keeps us away from Russell Crowe singing.

Now, it seems to me that there may actually be a contingent of artists working on the fringe of the American cinema whose work might reasonably be described as “post-ironic”—though not, I should emphasize, in the sense meant by “E Unibus Pluram,” which in its desire to recede into the innocence of traditionalism calls for something closer to pre-irony. I’m thinking of films like Zach Clark’s White Reindeer, Rick Alverson’s The Comedy, and particularly Alex Ross Perry’s The Color Wheel—films which seem at first to double down on irony and cynicism only to somehow emerge as richly emotional experiences. All three take an abrasive approach to comedy: White Reindeer makes a gag of conflating Christmas kitsch and grief; The Comedy finds its hero accosting nearly everybody he meets with confrontationally off-color remarks; and The Color Wheel, which I consider among the most significant American films of the last decade-plus and a key work of the modern independent cinema, spends it first sixty minutes working through a catalog of racist jokes, surreal non-sequiturs and intimations of brother-sister incest, all of it delivered in the kind of deadpan that makes it unclear what’s meant to be taken seriously.

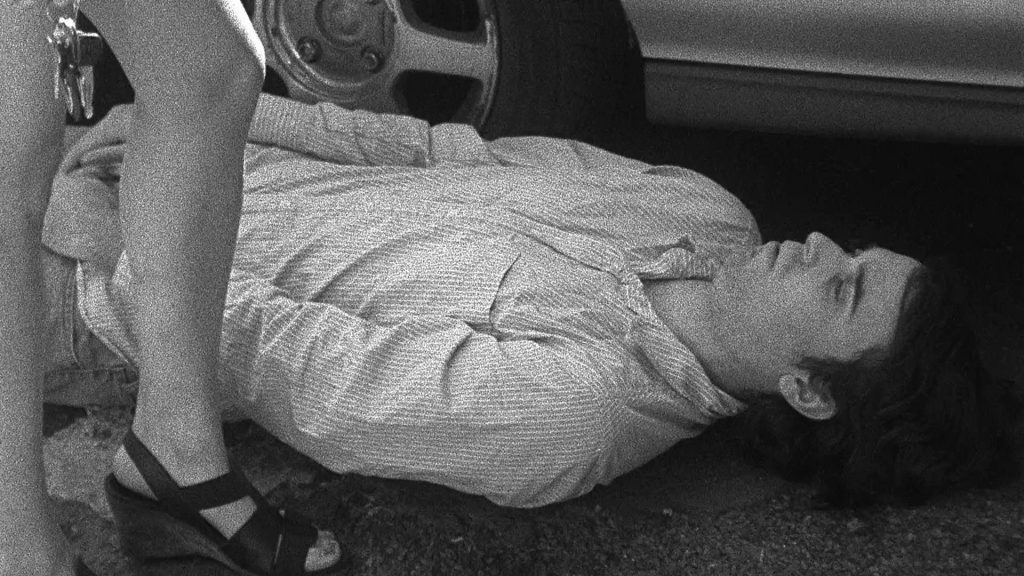

Over the course of The Color Wheel’s first hour, at least, it’s difficult to much sympathize with the plight of Colin (Perry) and his sister JR (Carlen Altman) as they endeavor to complete a protracted move from her ex-boyfriend’s New England apartment, a task they approach as if the effort required were practically Herculian. The story is archetypal: it’s a cross-state road-movie narrative, a tour of off-highway motels and American diners, and even, toward the end, a classical sort of high school reunion party. But Perry has devised a shrewd method of generic reconfiguration. The Color Wheel is grounded in the perspective of the siblings at its core, and all of the action which follows gravitates around their (temporarily) unified orbit. We the world, in other words, through the shared point of view of Colin and JR, brother and sister against the world. Encounters take on an uncanny quality—sometimes exaggerated, sometimes dreamlike. When they finally get to their hometown party, everything seems out of proportion: the natural sense of alienation eclipses reality until it colors everything we see.

These, of course, are the expected strategies of a straight-forward ironist, the sort of postmodern tactics Wallace would have argued show off the intelligence of their creator without offering much else of substance or lasting value. But in all three cases, the distancing effects ultimately have the opposite effect: they leave their audience unprepared to be so thoroughly (and earnestly) disarmed. When The Color Wheel suddenly pivots, in its final act, from a comic register to something more tragic, the effect is more pronounced than a simple tonal shift; instead it feels as though the parameters of the film have changed. An almost undetectable pressure, you realize, has been building through the picture. In the last moments the shield of irony is punctured and real life comes flooding in. It’s not that Perry has abruptly introduced seriousness into his otherwise comic framework—the device is too subtle, even elegant, to be dismissed as merely a gimmick. Rather, it’s that Perry has revealed the seriousness coursing through the comedy all along, recasting what seemed quite funny as basically sad.

This sensibility strikes me as uniquely equipped to contend with Wallace’s irony fatigue as well as its noxious counter-influence. It acknowledges, importantly, that popular culture is too far gone to embrace in absolute earnest, but it nevertheless remains optimistic that something more than dead-end irony and cynicism can be reached. The Color Wheel offers an emotional experience—its ending is genuinely moving—but one fortified by critical distance, a recognition of the inadequacy of the purely sentimental. We can’t just up and get rid of irony altogether: we need it to insulate us from the fundamental awfulness of consumer culture. It doesn’t help to willfully revert to some idealized pre-ironic tradition, no matter how insistently thinkpieces tell us that postmodern exercises are dead. Les Miserables is hardly the answer to our cultural woes. We need rich, full-bodied texts, savvy and at least a little cynical, to confront the modern condition head on.