‘A Clockwork Orange’

Reading books was once seen as a dangerous activity, luring women, considered universally weak of constitution, into a proprietary-free fantasyland, and thwarting men from achieving maximum virility. Now, reading (including in the academic sense) is seen as an endangered activity, threatened first by the movies, then the TV, the video game, and now the Internet in general, and those concerned have harnessed the scientific method to prove reading worthwhile.

Tests range from an MRI taken while literature students are analyzing Mansfield Park as proof that reading stimulates critical thinking to how reading literature can help develop empathy; two functions perceived as crucial to a great society or at least a civil one. (It’s no accident that the first things burned are books and those who read them.) Now that visual literacy is equally important who says movies can’t have the same impact? The only science of movie watching I’ve heard of is a theory called persistence of vision, how the mind fills in gaps between projected images. Much has been made of this collective dream state, a kind of hypnosis induced by spending half the movie in the dark. What is watched in this supposedly suggestive state has caused all kinds of alarm (Violence! Drugs! Sex!) but has also been seen as an opportunity. (See A Clockwork Orange.)

‘The Red Kimona’

Immigrants were believed to be socialized to American ways (read: Anglo-Saxon) as they crowded into the popular and cheap nickelodeons of the early 20th century. Films soon took a page from novels like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (slavery), Charles Dickens’s Little Dorrit (debt), and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (food safety, labor laws) to directly address society’s ills, with varying degrees of success. Take two by Dorothy Davenport Reid. The Red Kimona was one of many films made to bring awareness to (and exploit the salaciousness of) the ‘white slave trade and Human Wreckage exposed the perils of morphine addiction, which had claimed the director’s husband.

For a time the Soviets certainly believed in the power of films to indoctrinate and created whole new languages to do so, from the intellectual montage of Sergei Eisenstein to the kind truth of Dziga Vertov. (Later, what not to show became much more important.) Film noir, a product of Depression-era economics, war fatigue, pulp fiction, and the Blacklist, revealed our dark underbelly with its antihero in a chiaroscuro world requiring a more nuanced understanding of reality. Documentaries, for their part, have been betting on our suggestibility for years, hoping we’ll spring into action once the final, searing image fades onscreen. After one hundred years of trying, widespread transformation eludes us. (How many Inconvenient Truths do we need to stop burning fossil fuels? How many antiwar movies to end war?)

Small change does occur. Think Errol Morris’s Thin Blue Line and the (eventual) exoneration of Randall Dale Adams. But if it’s true that watching Fox News breeds conservatism (see Manufacturing Consent), surely the opposite is also true. Years of rendering gays, lesbians, and the transgendered visible in the mainstream surely contributed to recent strides in inequality under the law and Jewish Holocaust cinema helped to protect post-WWII Jewish culture.

How far can it go? Can hate of housecats be softened by thousands of kittens prancing on YouTube? Can iPhone footage of cows unbolting barn doors turn carnivores into vegetarians? Can viral videos of police brutality bring justice to black lives? And what, if anything, will The Wasp and Furiosa do to mitigate misogyny and improve the self-image of our growing daughters? Whatever your hopes or fears about movies and their influence, there is no doubt that they shape us. But can they be the equivalent of literature, something complex that given our deep attention fires all the right neurons making us somehow better? Can movies cure what ails us?

Rhino Season

The image from Bahman Ghobadi Turtles Can Fly of the horse struggling alone against the rushing current swung like an emotional wrecking ball at my heart. Ghobadi’s first film since escaping Iran has no less of an impact. Rhino Season depicts the shattered life of a Kurdish-Iranian political prisoner, jailed for almost thirty years and believed long dead. The diffuse light on the horizon dissolving into a hallucination of running with the rhinoceroses and the turtles raining down like rocks on the stone now hang on permanent exhibit in my head. Ultimately about the impossible contortions inflicted by tyrants, the film can’t be seen by Iran’s current tyrants but those closer to home certainly can.

The Great Man

If Sarah Leonor’s film about the return of two French Foreign Legionnaires from war doesn’t move you then check your MRI for signs of a sympathectomy. She starts by building the myth of Hamilton and Markov, two scouts, and their heroic exploits in Afghanistan. When the pair go home we move in closer to discover their civilian selves and wait to see if their unit will still hold. Even though they both live in Paris their worlds couldn’t be more different and battle on another front begins. Spare and restrained, this is no tearjerker but, in less than two hours, Leonor makes the case for humane immigration reform in any country.

Workingman’s Death

Maybe it’s all only catharsis and movies are already helping to do bare maintenance, keeping another Dark Age at bay. Furiosa kicking the shit out of a series of pewter-lipped war boys prevents us from going all Mad Max on each other. It could always be worse, after all, and this document of manual labor by the late Michael Glawogger shows us that it currently is in parts of Ukraine, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, and China. Exquisitely photographed, its incongruent beauty collides with the drudgery (and horror) of subsistence living and proves that you can reach the viewer with collective subjects. The resilience of these workers in the face of the harshest realities has the power not only to move you but also to earn your respect.

Hard to Be a God

Imagine the apocalypse and someone somewhere surviving in a cave long enough to devise a way to warn whatever civilization builds on our bones how to avoid our great mistake. What form will it take? Word-of-God parables, fairy tales, or, maybe, our modern equivalent, science fiction? If so, then Aleksei German’s Hard to Be a God is the message to send. It doesn’t get any more dystopic than the sludge, snot, and sickly filth of this feudal planet in a future without art. An allegory of the Soviet past, it also scarily resembles Europe’s Dark Ages, the arbitrary justice of almighty nobles, the suffering of everyone else, not to mention the total lack of public sanitation. The cautions of fairy tales usually go unheeded (don’t touch anything; don’t look back; don’t cut down the last tree) so, as difficult (and disgusting) as it is, don’t look away from German’s muck-caked vision of humanity—this is one future we don’t want to repeat.

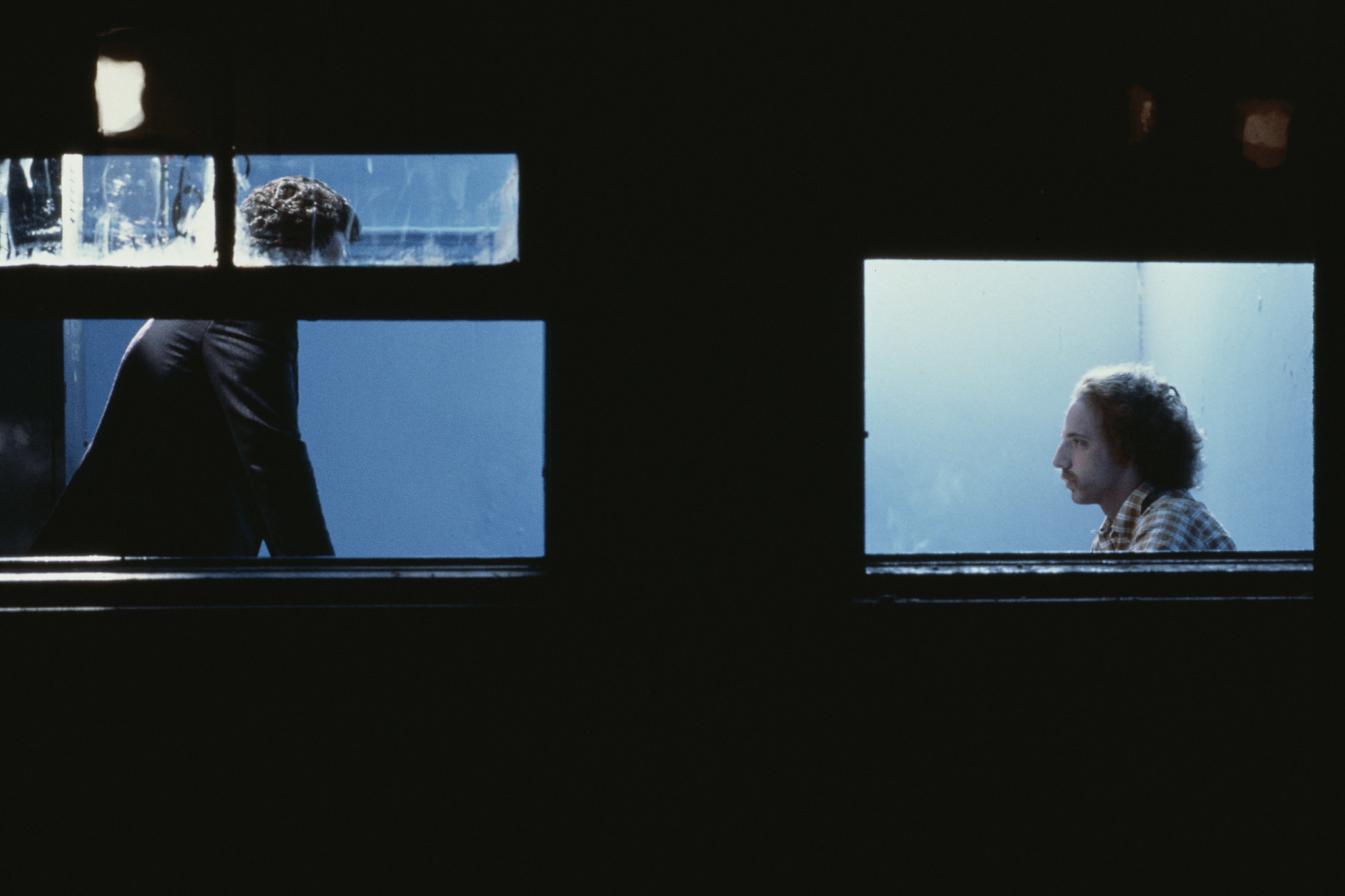

You, the Living

Or, as Preston Sturges proposes in Sullivan’s Travels, maybe movies’ best ambition is to make us laugh. Whether it’s Pluto stuck in the flypaper or Buster stoic amid the ruins of the storm-tossed house, other people’s troubles seem to be the funniest. In Roy Andersson’s film, the chuckles come from the absurd. In 2007’s You, the Living, our very dreams are the butt of the joke. One woman’s dream is to be understood, yet she cries while ignoring the one man who could. Another man dreams he’s standing trial for destroying a banquet of heirloom china in an ill-advised parlor trick. The deadpan executioner tells the prankster as he’s about to be electrocuted: “Try to think about something else.” Not merely setups for one-liners, Andersson’s situations offer plenty to contemplate; even in his sparsely appointed sets, the deep, diagonal compositions are rich in amusement. But you have to pay attention.