This article is the first in our limited series When Art Imitates Life.

In this edition, we explore the special place that Oakland holds in three 2018 releases:

Black Panther, Sorry to Bother You, and Blindspotting.

What does the term “black panther” mean to you? Is it a hero, or a villain, or something else entirely? For some, especially those fluent in recent United States history, the title of Ryan Coogler’s blockbuster hit, Black Panther, will inevitably invoke the political organization of the same name. Though the film makes no explicit reference to the group, the two cultural landmarks intertwine in a handful of meaningful ways. Perhaps most notably, the city of Oakland, California provides a foundation for both.

Marvel introduced Black Panther, essentially the first black superhero, in a 1966 issue of Fantastic Four. Just a few months later, in Oakland, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense). About twenty years later, Ryan Coogler was born in Oakland. He grew up in nearby Richmond. To see these dots as disconnected is to miss what is essential about a place and a filmmaker like Coogler, who, in an interview with The San Jose Mercury News, said, “…more than anything, growing up in the Bay Area gave me perspective on how a location influences the individual.”

A person’s hometown or homeland, in part, makes a person who they are. For the better or for the worse. Coogler may love the Bay Area, but he’s also acutely aware of the socioeconomic and racial problems endemic to both the place and the United States as a whole. His award-winning feature debut, Fruitvale Station, tells the story of Oscar Grant III, a young black Bay Area resident who was shot and killed by a police officer in 2009. The event, as echoed in the film, incited heated dialogue about the nature of police brutality.

In the Black Panther comics, the movie’s villain, Killmonger (played in the movie by Michael B. Jordan, who also starred as Oscar Grant in Fruitvale Station), was born in Harlem, but for the adaptation, Coogler opted to change his birthplace to Oakland. The film opens there, in 1992, on a group of boys playing basketball.

We later learn that one of these boys was a young Killmonger. On the night of that basketball game, he learned that his father, N’Jobu, had been killed. Over time, he discovered that N’Jobu was a prince of Wakanda. Wakanda’s then-king, T’Chaka, killed N’Jobu after learning that N’Jobu betrayed Wakanda by trying to sell their weapons in the United States. Angered by the treatment of African Americans and other minorities in the U.S.A and abroad, N’Jobu wanted to utilize Wakanda’s superior firepower to incite a revolution.

Like his father, Killmonger resents the ways in which African Americans and minorities across the world are treated and seeks to overthrow their political and economic oppressors. In many ways, Killmonger’s ideology mirrors that of the more radicalized members of the Black Panther Party. They, too, felt that exploitation was at the root of the world’s oppression, and wanted to arm African Americans.

As many have already noted, both on social media and in editorials, the image of T’Challa on the throne of Wakanda in the teaser poster, and the image of Killmonger defiantly sitting on the throne later in the movie, both draw a purposeful resemblance to the iconic photograph, captured by Blair Stapp and Eldridge Cleaver in 1967, of Huey P. Newton sitting in a wicker chair armed with a spear and rifle. It’s important to note that the characters of T’Challa and Killmonger are analogs for real groups of people. So it’s fitting that these images convey symbols of black power and nod to both Africa and the diaspora. When people talk about why representation in media is important this is what they’re talking about.

A lot of people are telling me the #BlackPanther poster reflects Black Panther co-founder Huey P. Newton’s photo. If so, this is awesome. pic.twitter.com/OtXf5Xwm6v

— Laura: body@SDCC; mind@Goldblum statue in London (@lsirikul) June 9, 2017

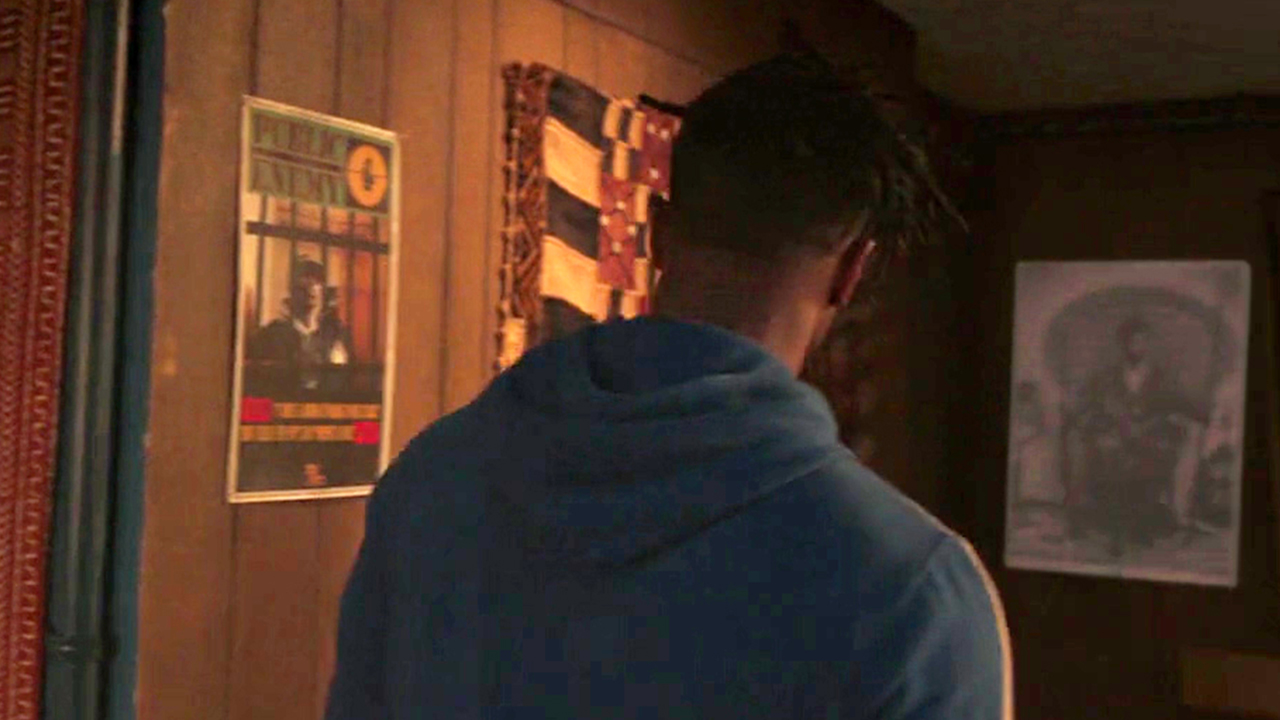

As part of their royal rite of passage, both T’Challa and Killmonger must enter a hallucinogenic state in order to visit their respective “ancestral planes.” For T’Challa, the plane is the breathtaking African Savannah. For Killmonger, it’s his father’s dingy Oakland apartment. Eagle-eyed viewers might spot that same Huey P. Newton photograph on the wall of the apartment. While in his trance-like state, Killmonger converses with his father and, referring to his place of birth, says, “Everybody dies around here.” We may not agree with his methods of action, but we can understand the roots of Killmonger’s passion, and his response to the injustices that he experienced.

In response to the injustices that they experienced, the Black Panther Party launched a host of “Survival Programs” intended to give community aid and provide everything from education and tuberculosis testing to legal assistance and free shoes for the poor. Here, too, the Oakland of Black Panther echoes the history of the Black Panther Party. The closing scene of the movie mirrors its opening, with T’Challa visiting that very same Oakland basketball court, having resolved to use Wakanda’s science and technology for the greater good.

Though it’s remarkable what Coogler accomplished within the Hollywood system, being the blockbuster MCU movie that it is, Black Panther can ultimately only take a passing glance at these socioeconomic and cultural issues, and plenty of criticism has been leveled at it to that effect. Some argue that T’Challa’s final gesture amounts to toothless and empty philanthropy, a sort of gentrification housed under the vague guise of liberal social outreach and information exchange. It’s more than an ocean that divides Killmonger’s Oakland from T’Challa’s Wakanda—it’s also wealth, opportunity, love, and support. After all, it’s not a coincidence, nor is it down to the Bay Area being Coogler’s home, that he switched Killmonger’s birthplace from Harlem to Oakland: It’s because where a person is from informs who they become. Wakanda helped make T’Challa a hero. Oakland, and the racial and socioeconomic injustices experienced thereby too many, made a small boy into Killmonger.