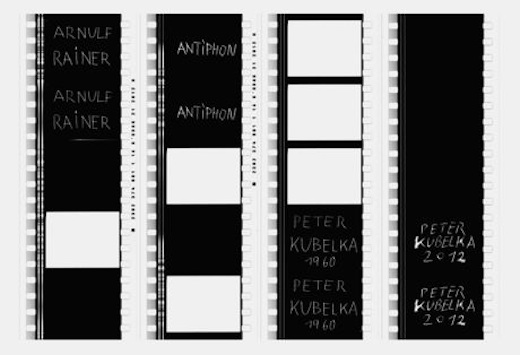

There is a glorious irony, by no means overlooked by documentary filmmaker Martina Kudláček (In the Mirror of Maya Deren), in the fact that her film Fragments of Kubelka is a nearly four-hour excursion into the work, life and philosophy of a man whose own cinematic output is characterized above all for its absolute, almost crystalline density and parsimony. Peter Kubelka, the Austrian avant-garde master whose career began in the 1950s and has in many ways set some of the fundamental terms for modernist experimentation in cinema, has produced a slender but powerful body of work: seven films total, plus a new work, Antiphon, based on a reversed score of his 1960 film Arnulf Rainer. Not counting Antiphon (or Monument, which is a projection-event of Antiphon and Arnulf Rainer shown together), Kubelka’s entire output to date can be screened in exactly 63 minutes. And so, Kudláček’s film (or should we stipulate, her HDCAM digital work, which is significant here) “bests” the Kubelka canon in terms of running time by a not-inconsiderable two hours and forty-nine minutes.

‘Fragments of Kubelka,’ as a work of digital video, is of necessity a translation of works and ideas that are as firmly steeped in the concrete language of celluloid as, say, architecture is grounded in the enclosure of space by rock, wood or steel.

There’s even more irony at work, of course, in the fact that this relaxed, ambling documentary is called Fragments of Kubelka, since the word “fragments” implies pieces or shards. There is more to Kubelka, the title announces, than what Kudláček has presented here, and we are only getting small bits and pieces! Could the Director’s Cut potentially be even longer? But then, “fragments” also implies that what is included within Kudláček’s purview is presented in an incomplete manner. In some very deliberate ways, this is quite correct. Over the course of Fragments, we see and hear Kubelka talk about some of his films. But we never see them directly. This is because the films are films, in a very basic, medium-specific manner: light, dark, sound and silence, only occasionally resolving into imagery. Kubelka speaks at length about how crucial it is to honor the material provenance of things, not to blithely attempt to substitute one thing for another. And so, when Kubelka talks about his Arnulf Rainer (which is a symphony of black-and-white frames, with an alternating, on/off buzzing soundtrack), we see very little of it on screen. Mostly Kudláček shows us how the film moves through the projector, or how it darkens or illuminates the space in which it is projected. That is, we see the film’s secondary effects. (And, for what it’s worth, when we see Arnulf Rainer on the screen, it produces a distracting roll-bar effect, because its pure filmic intensity cannot readily translate to any form of video. It only generates feedback.)

Similarly, Kubelka and Kudláček mostly show us the film Adebar (1957) as its maker rolls out lengths of a 35mm print and cuts it with scissors, or as it is installed on a gallery wall. The film becomes less of a projected entity than a sculptural object with which Kubelka can discuss the relation of film rhythm to the proportions of the body. Adebar is organized in series of twenty-six frames, which Kubelka likens to the approximate length of his forearm. Likewise, one of the man’s most famous films, the anti-colonial, sound/image disjuncture masterpiece Unsere Afrikareise (1966), is shown in very small clips on a Steenbeck flatbed editing table, as Kubelka winds the film slowly through the viewer, bit by bit. In so doing, he helps to analyze the minute relationships between shots, in terms of matches on movement, shape and gesture, or the “sync events” he created through the collision of jarring images with unexpected but highly suggestive sounds (e.g., gunfire with a hat being blown off by the wind; a dead zebra’s leg shaking as an Austrian exclaims in German, “Let’s go, now!”). Kudláček works with Kubelka to allow us to see his films in ways that we would never have been able to before.

But what we don’t get—and this is vital—is the illusion of unmediated access to “the films of Peter Kubelka.” This is because Fragments of Kubelka, as a work of digital video, is of necessity a translation of works and ideas that are as firmly steeped in the concrete language of celluloid as, say, architecture is grounded in the enclosure of space by rock, wood or steel. We are given something that the art of documentary allows us to receive, as a supplement to these films, a kind of movement or situation alongside them. (And it’s worth noting, Kudláček, for whatever reason, does not even touch Kubelka’s first and last films, Mosaic in Confidence [1955] and Poetry and Truth [2003]—and it’s not as if she lacked the time to do so!) So in some sense, Fragments of Kubelka installs at its very core a kind of modernist frustration. We are taken on a lengthy journey, all around the desired objects, only to circle them, approach them and find that they must finally reside elsewhere.

‘Cinema’ bobs in and out of these talks, but Kubelka is quite deliberate in refusing to keep it front and center. What we typically think of as the world of film is in fact connected to everything else, as our viewing habits and our education militate against this deeper understanding of its place in human history.

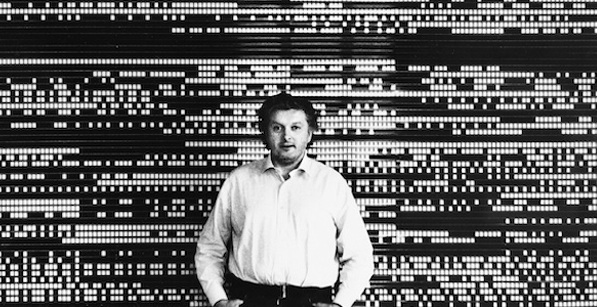

So what is left? Where does the time go? Kudláček has provided us with a bracing yet affable truth about Peter Kubelka, one that many have known for years but that has never been inscribed or, if you wish, monumentalized in this manner until now. There are many reasons why the art of Kubelka is such a small residue in comparison to its influence and significance. The major reason, naturally, has to do with his working method, which is chiefly about heightening the “articulation” or the level of difference between each film frame, to a communicative maximum. In this regard, Kubelka really is cinema’s answer to Anton Webern or Gertrude Stein. However, Kubelka has long been known for his expansive lectures on the history of cinema, its philosophical foundations, its relationship to cookery, and a great many other broad humanistic topics. Fragments of Kubelka begins not with an extended discussion of film per se, but with Kubelka using a broken, timeworn oil lamp as an example of what the camera, as a detached eye, really is, as compared to the sluggish, skull-bound eyes with which we typically visualize the universe. He then uses two wooden tabletop sculptures to expound on gravity, nature, and the need for tactility as a way to understand aesthetic relations. He pauses for a brief excursus on the importance of Étienne-Louis Marey’s chronophotography for all future modern art. He considers his own family history, with several narrow escapes from fascism hovering in the background. He even stops to have a rather uncomfortable interaction with a life-sized nude statue of an African woman.

“Cinema” bobs in and out of these talks, but Kubelka is quite deliberate in refusing to keep it front and center. What we typically think of as the world of film is in fact connected to everything else, as our viewing habits and our education militate against this deeper understanding of its place in human history. What Kudláček has given us, in some sense, is the “invisible” work of Kubelka, the immaterial erudition and evanescent productivity that defines his career beyond his physical films. Some artists—Stan Brakhage, Ken Jacobs, and the late Mark LaPore—have been almost as defined by their pedagogy as by their art. Kubelka is clearly in this league. So seldom is this non-physical labor preserved; like a good meal, it has the tendency to nourish the assembled and then evaporate in time, its further results being seen only in the historical long view. Fragments of Kubelka not only makes this “invisible” art visible; it places it on equal footing with Kubelka’s films, showing them as coextensive of one another.

Speaking of invisibility, Kubelka once designed a theater for Anthology Film Archives called the Invisible Cinema, a space that permitted viewers to only see the screen, and nothing else. This is a fantastic spatial-thought experiment, and of course certain films would be very well served if seen without undue distraction. But having seen Kudláček’s extended profile of Kubelka, it now seems like an extremely odd kind of laboratory experiment, this cordoning off of cinematic knowledge. Fragments of Kubelka is a peripatetic ants’ path hand-in-hand with a man whose work certainly insists on the unique material character of things, but for whom “cinema” is an ever-expanding network, ultimately related to everything and everyone.