Some filmgoers and even a few critics have been rather vocal about cinematic “bloat,” a perception (partly true) that the running times of mainstream movies have gotten progressively longer in recent years. Certain Hollywood yardsticks that seemed to be firmly established since the late seventies-early eighties blockbuster era—the two-hour drama and the eighty seven-minute comedy—appear to be less stringently applied these days, and while you would think that audiences might appreciate getting more for their inflated ticket price, there’s mostly just kvetching. Why should The Avengers be 143 minutes long? Why do we need 116 minutes of That’s My Boy? Even a children’s cartoon like Wreck-It Ralph clocks in at a fuss-inducing hour and forty eight minutes.

So although Variety editor Josh Dickey comes off like a fool when bloviating that no film should ever be longer than two hours—his entertainment-over-art absolutism is practically a parody of bottom-line Industry groupthink—it is worth considering whether contemporary running times are expanding beyond their movies’ having anything pertinent to say. After all, duration is an aesthetic parameter, like color, composition and camera movement. It’s very likely that we’re seeing films getting longer because of their ultimate destination on DVD and Blu-ray, media in which more bang for the buck really is constructed as representing the better bargain. (To take one example, consider the fetish for deleted scenes. If they were not ultimately included in the film, they should hypothetically be of interest only to researchers. But clearly they represent a “value add.”)

Griffith felt that films such as ‘Intolerance’ and ‘Way Down East’ required very long running times, so as to cultivate bourgeois audiences capable of giving cinema the same concentration they frequently afforded 19th-century literature.

In addition, extended DVD rentals and two-day VOD windows often encourage split viewing, watching a single film over two or more days. In this case, a film that is longer than two hours actually provides better entertainment, since it expands its cognitive footprint, as it were, allowing for more watching spread across longer periods of time, the longer sessions allowing the film to remain in the memory from night to night. It seems that, for the mainstream film watcher, the advent of home video and the encroaching death of public cinema is driving a commercial imperative towards longer films, even as moviegoer finds him or herself frustrated by the inevitable shift. At the cinema, we grow restless, but at home, we are all “becoming Hindi,” as it were. Like Bollywood audiences, we watch, take an intermission, come back and watch some more.

What gets lost in this discussion about changes in running times, of course, is any sense of history. In the earliest days of cinema, of course, films were around a minute in length; before long, Edison and Méliès expanded films into multiple reels. More significantly for this topic, the lengthening of films during the silent era was understood to be a fundamental component of their incipient legitimacy as an artform. Griffith, as the late Miriam Hansen explained, aspired to create cinema that was the aesthetic and the moralistic equivalent of the Victorian model. As such, he felt that films such as Intolerance and Way Down East required very long running times, so as to cultivate bourgeois audiences capable of giving cinema the same concentration they frequently afforded 19th-century literature. By the same token, European cinema of the silent era, and German cinema in particular, came to recognize itself quite early as an “artistic” alternative of Hollywood dominance. Thomas Elsaesser has written about Weimar cinema’s eventual self-branding as a highbrow Expressionist mode of cinematic art, set apart from rank commercial concerns and appealing to the cosmopolitan intellectual. Like Griffith’s cinema, Weimar films could often expand beyond the usual running times, mostly because they were understood to be appealing to a specialized viewership, for whom the free expression of the auteur was a “selling point” if anything.

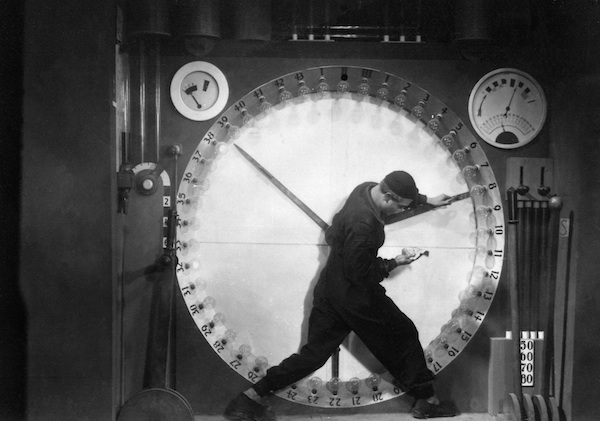

This brings me to my analysis of this month’s film, Fritz Lang’s 1922 masterpiece Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler. Arguably Lang’s first major film, and the fourth of his many collaborations with screenwriter and future-wife Thea von Harbou, the 270-minute film is divided into two halves, those halves divided into “acts,” not unlike a stage play. However, this is where any resemblance to theatre ends. Mabuse is strikingly modern cinema, a signal of things to come from Lang and, in many respects, a touchstone for later gangster cinema, films of the supernatural, and movies patterned on the confrontation between a super-criminal and a shrewd, determined cop. It seems like pandering to say so, but at the same time it seems to me that it ought to be said—whatever stereotypes come to mind when conjuring a mental image of “silent film” are virtually absent in Dr. Mabuse. Lang has so keenly paced and organized the film, and its visual style is so remarkably crisp (especially in this recent restoration), that the film represents top-drawer entertainment as well as being a high-water mark for the artform. Think of it this way: it’s only at about the three-hour mark that Lang employs camera movement, and I honestly doubt most viewers would notice or care.

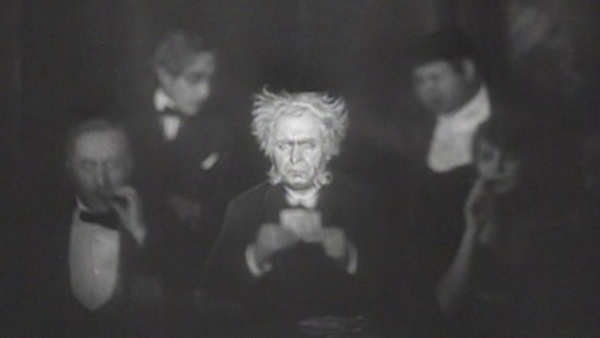

Why is Dr. Mabuse such a forward-looking piece of modern cinema? It’s not just that it operates within certain recognizable genre parameters. Many other Weimar classics, such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu, and Lang’s own Metropolis (made just five years later) are genre films, at least in part. But Mabuse is comparatively realistic, treating its tale of psychological control and villainy with a relatively straightforward visual approach. The editing alternates between master shots and close-ups; rich, contrasty cinematography and highly detailed mise-en-scène lend a solidity to the film’s many environments, even those (such as the dual-level Petit Casino) that verge on the abstraction Lang will explore more fully in later films. Within this generally realistic framework, the stilted, brain-fever quality to much of the acting (Rudolf Klein-Rogge as Dr. Mabuse in particular) seems less like the signifying pantomime sometimes associated with silent film performance, and much more like an expressive choice based on the film’s specific subject matter. After all, Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler is primarily concerned with hypnotism and psychological control, weak minds becoming mere playthings in the hands of a master manipulator.

‘Mabuse’ is strikingly modern cinema, a signal of things to come from Lang and, in many respects, a touchstone for later gangster cinema, films of the supernatural, and movies patterned on the confrontation between a super-criminal and a shrewd, determined cop.

If this theme sets off any alarms of recognition for you, you’re certainly not alone. In his classic 1947 study of Weimar cinema, From Caligari to Hitler, the renowned critic and theorist Siegfried Kracauer argued that the cinema leading up to the Third Reich consistently depicted evil, charismatic men who employed hypnotism or other nefarious means to exert their will over seemingly ordinary Germans. What’s more, Kracauer claimed that, despite the obvious criminality and diabolical character of these men on the film’s surfaces, most of the films, Dr. Mabuse included, displayed the unconscious desirability of losing control to the stronger man—the Freudian uncanny, as it were, wherein the horrifying loss of the self has an unexpectedly masochistic appeal. We see this most of all in the character of Cara Carozza (Aud Egede-Nissen) the nightclub dancer who all but throws herself at the madman. But the weak-willed Count Told (Alfred Abel), who becomes a card cheat and a maniacal hermit under Mabuse’s influence, also seems to take some unspoken pleasure in buckling under Herr Doktor’s all-enveloping influence. And of course, in one of the film’s most impressive setpieces, Mabuse performs disguised as the great Sandor Weltmann (a vaguely Jewish name that literally translates as “world-man”) for a packed house at the Symphony Hall. The audience gives him ovation after ovation for manipulating various individuals (including Mabuse’s arch enemy, State Prosecutor Wenk [Bernhard Goetzke]) with his feats of mesmerism.

So it seems likely that Kracauer is correct, that Mabuse serves as a proto-Hitler figure, garnering adulation for controlling the masses. (And let’s not forget that von Harbou herself joined the Nazi Party, at which point the anti-Fascist Lang divorced her, leaving Germany for the U.S.) But Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler is in fact a complex, capacious film that cannot be reduced to a single allegorical reading. This too explains the formal necessity of its length, and why that expanded running time is experienced as richness and expansiveness rather than that dreaded “bloat.” After all, the Weimar era was a period fertile for unrest and anxiety on many fronts. The relative newness of Freudian psychoanalysis (The Interpretation of Dreams was less than 25 years old at the time Mabuse was made) helps to explain why the Mabuse character, an evil psychoanalyst, could serve as a figure of popular menace. The very concept of the unconscious—a hypothetical part of the psyche more accessible to the outside expert than to the individual him/herself—was and still is a frightening prospect, provoking a feeling of deep vulnerability.

Again, the sprawling multi-act structure of Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler permits the exploration of multiple cultural forms and motifs, while at the same time successfully subsuming them within the broader narrative. Other seeming tangents within Dr. Mabuse, such as Count Told’s penchant for collecting Expressionist art, or the proto-feminist independence of the Countess Told (Gertrude Welcker), or even the vague hints that the effeminate Count and flirtatious Countess share a marriage of convenience, all point to the various forces of social and cultural change thrumming through the Weimar Republic in 1922, and tragically, the very modern progressivism that the National Socialists will eradicate. Fritz Lang depicts these forces in an uneasy triumph over Dr. Mabuse. After wreaking havoc across the social sphere in his various guises, with mental manipulation as well as sheer thuggery, the Doctor himself succumbs to madness. But then, Lang produced two sequels in the sound era—The Last Testament of Dr. Mabuse in 1933, and The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse in 1960. Of course, 1933 was also the year Hitler came to power in Germany. But then, 1960 was the year that Adolf Eichmann was captured in Argentina. In real life as well as in the movies, Mabuse rises and falls, again and again.