Hopefully we still have not forgotten that the Iranian filmmaker and social activist Jafar Panahi awaits the start of a six-year prison term and soon can be confined to Evin prison, the horrific place that has become a second home to many Iranian intellectuals in the last ten years.

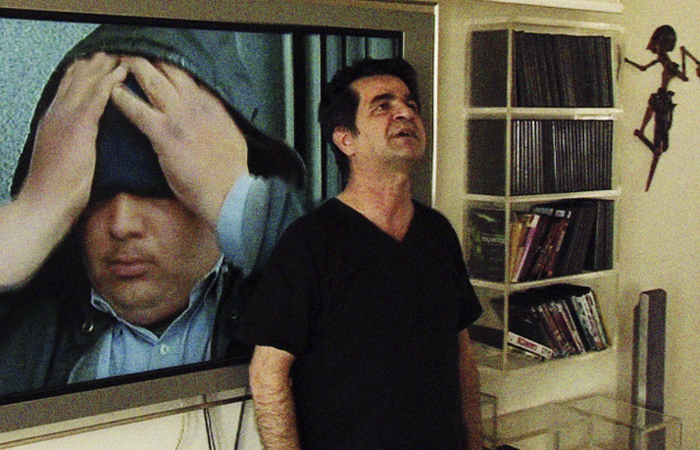

A thick-skinned fighter, Panahi has been deprived of all his rights as a citizen, including the right to make films. Even so, in the era of self-styled Iranian neo-McCarthyism, he has managed to make a “non-film,” This Is Not a Film, a powerful statement on the existence of cinema within one individual, rather than through formal ways of filmmaking.

In the wake of the Panahi’s sentence, many people in the world of cinema have objected to its brutality and preposterousness, and some of the related activities have been documented in David Hudson’s coverage of the events following the verdict. However, the horrifying fact that he can be removed from his modest northern Tehran apartment to where he does not belong looms large on cinema and freedom of speech. The British Film Institute’s attempt to keep Panahi present in our memories, by organizing a complete retrospective at the National Film Theatre along with Panahi’s colleague, Mohamad Rasoulof, is an auspicious event that needs to be taken to other countries where cinema is also considered a liberating art form.

An alumnus of the College of the Radio and Television in Tehran, Panahi started his career in the southern Iran with two 16mm short films which dealt mainly with the social and cultural issues of the region. Upon his return to the capital city of Tehran, his search to find producers to materialize his projects bore no fruit and left him in frustration. Panahi then learned that Abbas Kiarostami, his favorite Iranian filmmaker and an influence on his 16mm projects, was about to start a new film. He found the director’s phone number and left him a message that eventually led to his job as assistant director in Under the Olive Trees (1994, also playing at the BFI season). It is also notable that before this association, which continued till 1997 with Taste of Cherry, Panahi had paid tribute to Kiarostami and his classic The Bread and Alley by incorporating a scene in his short film The Friend (1992), in which a little boy stands in front of a theater showing a Kiarostami film.

Later on, Panahi gave Kiarostami the outline of a story about a girl looking for her lost money some hours before Iranian New Year’s eve, and Kiarostami wrote The White Balloon (1995) based on it. Thanks to Kiartostami’s presence as screenwriter, Iranian Channel Two (one of just three TV channels in 1990s Iran) financed the project and thus made it possible for Panahi to direct his first feature. After finishing the film, Panahi, who had never been abroad, attended the Cannes Festival for the screening of The White Balloon and brought a Caméra d’Or back home for what he calls the “sincerity and frankness” of his cinema. This glorious moment marked the beginning of the end of his distressful career in Iran.

Critics started claiming that these films merely showed Iranian’s daily life and the reality on the streets which, to some extent, is true. But what is inspiring in the works of a director such as Panahi, is turning the process of depicting reality into a remarkable cinematic experience even for those who live in Iran and are part of the day-to-day experience being portrayed on the screen. One can sense that there is something beyond social commitment or a pure neorealist attitude, which Panahi himself describes as “a fresh look at the very reality that the spectator encounters in everyday events.” His films, much like those by Chilean documentary filmmaker Patricio Guzmán (whose films and their extended screening were the most important cinematic event of London in July), are a brave and overtly critical response to the situation in his country. In this sense, his most outstanding films are those which he attempted but never managed to finish or even start. He was the filmmaker whose ideas were as dangerous for the State as were his finished films.

The White Balloon is the only Panahi film which is widely shown in Iran and has almost become Iran’s answer to Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, as it used to appear regularly on TV during New Year’s Eve. Like Capra’s film, it is a charming and heartfelt message of mutual understanding and compassion that invites all tribes and various people in the country to sit around the traditional New Year’s table, even though some don’t speak the same language; Panahi himself is from an Azari language family.

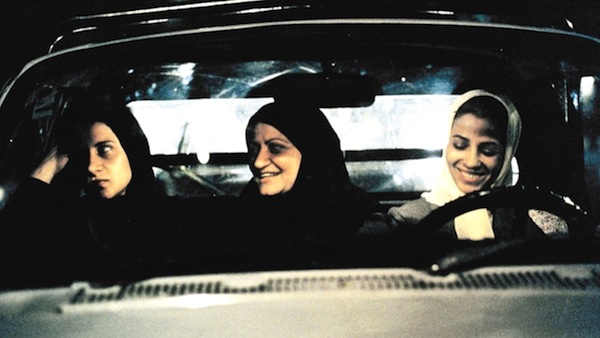

His second feature, The Mirror, can be described as what Mark Cousins calls an “urban odyssey in Iranian cinema,” the suffering and discoveries of a voyage in the metropolis, usually endured by children in their search for their identity and status in a patriarchal society. But also, in this film, the issue of what is reality and what is its cinematic representation becomes more central and it even outruns themes mostly associated with children’s films in Iran.

For obvious reasons, since The Circle (2000), Panahi’s films have never seen the light of screen in Iran.

What follows is a collection of interviews with Panahi that have never been published before in English or outside Iran. Here, anyone can see the filmmaker’s clear and fearless understanding of the path he has chosen. I have omitted the questions in order put the spotlight fully on the answers. I must thank Iranian Film Monthly for their permission to re-publish these materials. Chronologically, the first interview was conducted by Houshang Golmakani, chief editor of Film Monthly, whose journal has supported hundreds of post-revolution films and filmmakers, through nearly 450 odd issues. The saga of keeping that magazine running in what he calls “the minefields of Iranian cinema” is no less miraculous and inspiring than the great Iranian films we have watched. In a 1997 interview, Golmakani was accompanied by film critic Majid Eslami. Finally, the longer piece—from which I have taken certain excerpts—is the result of an interview by Ahmad Talebinejad, whose arts and cinema magazine, Haft, was banned 5 years ago. Undefeated, Talebinejad started another journal, called Arzhang, but this time it was banned right after the first issue.

My thanks go to all these people in Iran who keep advancing with courage through the minefields of cinema.

The Interviews

Early Days

Before making The White Balloon, I made two shorts (The Friend and The Last Exam). I gained experience through them and in The Friend, I emphasized the acting aspect. After I graduated from college, I went to work in the Radio and TV Center in the city of Bandar Abbas; I continued the practice of using child actors as in The Friend. In the second film, I focused on découpage. When I returned to Tehran I hastened to make a professional feature film. After watching many Iranian films over and over again, I realized my potential was no less than the directors of those films.

I was desperate to make a film, so I said yes to a professional producer. After I began shooting, I found it a vulnerable project and decided to stop. But when I started The White Balloon, I asked a nonprofessional producer to make it because I didn’t want them to interfere in the making of the film.

The White Balloon

I started with a brief sketch and spent a lot of time on it before leaving it to Kiarostami. In this sketch the focus was on the events and narrative; but after Kiarostami wrote the script it was the characters in supporting roles that came to the foreground… the people who couldn’t attend the New Year’s Eve, each for their own reasons. Each of them seemed to me as a painting. So the story of losing the money and buying fish became an excuse for standing in front of these paintings and looking at them.

The Mirror

I decided to make The Mirror in a situation that was very similar to McCarthyism. In The Mirror, the primary motif is the criticism of social morality. We live in a world in which people show-off, but they still don’t believe in their own words. This was the main theme of the film. That’s why the film is called The Mirror. The film intends to reflect the realities. In the sequence where the girl rebels, she is, in fact, protesting against the other actors, because she is a witness their pretentious behavior. Then we follow her with a candid camera, and we see two different realities—a real image and a figurative image of reality. And they are not too distant from each other. This could be considered as a kind of style, but I don’t mind that.

Working with Children

I had a painful childhood, and I always believed that the adults were responsible. Therefore, I have always kept reality as my haven instead of imagination. My teenage son is interested in action and SciFi films, but when I was at his age, I loved The Bread and Alley.

There are too many Iranian films about children, while there are hardly any for children. This is also a result of the social conditions. I mean when you’re not able to express your words in regard to the adults (because of censors), you transfer them to the children and speak through their language. There may come a day when the social conditions change and the Iranian film-makers do not have to choose the children’s language and world. I admit the fact that the children have been our pretext.

Technique

In France we visited a location at which they were shooting a scene of a French film. There were at least ten cine-mobiles there, while we don’t even have one of them in Iran and we don’t need them. To make The Mirror, I had a crew of six, and I didn’t need an inefficient seventh one. We shot The Mirror in a Tehran traffic jam and we did it without any problem. But if you do the same thing in Europe, you have to ask for all different types of permissions. Why don’t we have continuity girls at work? The reason is we do the details by ourselves.

Documentary-Style

You know, I’m experiencing. Thus it is natural that those films with social themes should have seemingly simple and documentary-like structures. If you have seen most of the notable Iranian films, even some pre-revolution ones, you will notice they are constructed in this way; meaning that we are always suffering from the main social problems.

Sound

Once I worked with someone who believed every sound in the film should be heard clearly. In my opinion it could be heard if necessary. I think it should be like nature; if we want we can hear it. But at that time I didn’t have enough confidence. Because technically I didn’t have enough experience with sound. In each film I was experimenting with something; in one film working with actors, in another shooting script. I usually left sound to others. Under the Olive Trees was excellent, because I realized that you don’t need to know every technical detail. You should only know different meanings that sound may impose.

Talking about reality is a mistake. There isn’t such a thing as reality in cinema. How can we find the limits of this reality? We are arranging everything from the beginning. Even by choosing the lenses we are manipulating the reality.

Music

I asked Farshid Rahimian to write a score for The White Balloon. I thought any feature film needs music. After he composed the score it didn’t seem to suit the film. I asked him to try again. The second one had the same problem. Then I realized that it is not about whether the score is good or not; this film didn’t need any music and the background sound could be the best soundtrack. The problem was me being an amateur and I didn’t realize from the beginning.

Reality

Talking about reality is a mistake. There isn’t such a thing as reality in cinema. How can we find the limits of this reality? We are arranging everything from the beginning. Even by choosing the lenses we are manipulating the reality.

Leaving Iran

I was offered the opportunity to make films abroad, but I declined for two clear reasons: First, I don’t know those countries very well and secondly, I am familiar with my own culture and nation. In any case, one can make a low budget film in any country, but one has to apply different approaches.

Going Commercial

Some years ago when I was having severe financial difficulties, I was asked to direct a number of low routine shows. I agreed, but the following morning when I got up to go to work, I felt feverish and fell sick. Now if you don’t take it as a proud boast, I can say that I can make fantasy and commercial movies as well. Every filmmaker has such a potential, but it is his scruples that matter and forbids him to lean toward vulgarity.

The Foreign Audience

Like many others, I thought maybe political issues regarding Iran or talking about poverty attracted the foreign audience. But this was not the case. Among different subjects discussed in interviews, it was mostly the humanist sensibility present in Iranian films that attracted them. Some foreign films made about Iran sometimes give false impressions about us and our films can change the opinions. After one of the screenings of the film, an old lady asked me about Not Without My Daughter. She thought it had a different atmosphere and there wasn’t any pool with fish in the houses in this film. I explained to her that this is a part of Persian architecture and I told her about fish in Haft Seen (the traditional table setting of Iranian New Year). I reminded her that Not Without My Daughter was not made by an Iranian, and it was not shot in Iran. I think even the worse Iranian films can have a positive effect.

Censorship

We have always lived under exceptional conditions. In the Iranian film industry a filmmaker consumes only 10 percent of his energy on directing a film. The rest is wasted on marginal affairs from the never-ending conflicts with the censors to the equipment of the needed apparatus. When I wanted to select the cast for The Mirror from among the students, I was forbidden from entering the school because I was accused of doing propaganda for Christians in The White Balloon (one of the good characters was an elderly Christian lady). Moreover, the Ministry of Education forbade the students to watch the film. Finally, I got permission for my assistant to enter the school. Anyhow, it was possible to find another way. The Iranian cinema industry has proved that the filmmakers must be thick-skinned people in order to achieve their goals, so I’m not worried about the hard times ahead of me. The real agitation occurs when you are forced to surrender to the imposed situation. There are those filmmakers among us who haven’t surrendered to such situations, and they haven’t made any films for seven years.

Iranian Cinema

[Iranian] cinema says that humane and lovely moments can be created through simple matters. This causes the foreign spectator to acquire the power to discover the ideas and get pleasure from this apocalyptic discovery. This is contrary to the commercial world cinema that subjugates the spectators and causes them to deviate from discovery.