If you’re going to make a film about someone (particularly someone relatively well known), there are established ways of going about it. “Established ways,” though, are usually quite tedious to watch. They follow a particular format. They begin here. They end there. The space in between details the events from here to there. There are thousands of such documentaries. A few are good. Most are not good at all.

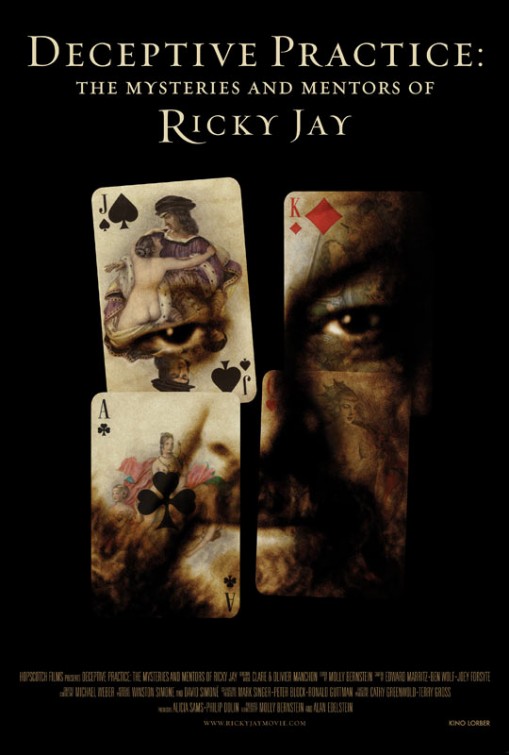

If you’re familiar with Ricky Jay or you’ve read any of his books or seen him in any films or even attended one of his performances, you might want to know more about him. You may have some interest in a conventional documentary about his life. Fortunately, Deceptive Practice is anything but conventional. A hint of that exists in the rest of the title: The Mysteries and Mentors of Ricky Jay. You’ll ultimately learn a great deal about the individuals that influenced Ricky Jay and isn’t that a better process all around?

Fandor co-founder Jonathan Marlow spoke with filmmakers Molly Bernstein and Alan Edelstein back in June about Deceptive Practice, Ricky Jay and Jay’s mentors, accordingly.

Jonathan Marlow: Your respective filmographies definitely reflect an interest in biography. That is a most welcome attribute. Since you have tackled Ricky Jay from the perspective of his mentors and influences, I wager we should begin with Mark Singer and his article in The New Yorker that, in essence, was the inspiration for this film.

Molly Bernstein: I had first discovered Ricky through one of his books, Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women, and then saw him on the stage. It was after I saw a live performance that I looked him up and found The New Yorker profile. It’s an extraordinary portrait of a very intriguing character with many things going on in his life. That is really what inspired me to think it would make a great film.

Alan Edelstein: And I thought that we should work on the film together. She had the suggestion of writing to Mark Singer (which we did). Mark was very instrumental in helping us gain Ricky’s trust and get the project going. That was somewhat lucky for us because it was a cold call. Or a cold letter, I should say, to Mark. We just got along and it worked out.

Marlow: The performance that you saw was ‘Ricky Jay and His 52 Assistants,’ I presume?

Bernstein: Yes.

Marlow: That is essentially the first thing that we see in the documentary, the performance at the Old Vic in London. How long of a process was the making of the film? It is a loaded question because already seems apparent that it was a long process.

Bernstein: Definitely over a decade. It’s probably thirteen years, total, from when we started…

Marlow: I believe that the Old Vic performance was from 1999.

Bernstein: Yes. That is the first thing that we shot, actually. One of the first things.

Marlow: I saw the same show at the Geffen Playhouse not quite that long ago. Like yourself, I’m quite fond of his books. I think I first came to be aware of Ricky Jay through House of Games. I lived in the Pacific Northwest when the film was released and not many films were made in Seattle at the time. He has such a fascinating presence as an actor. He carries a similarly remarkable presence in his stage shows. I was pleased that you spent time talking with David Mamet [director of House of Games and several of Jay’s stage shows] in the documentary. Their working relationship is a very fascinating one. I’m glad you were able to capture that.

Bernstein: Between the two of them?

Marlow: Between the two of them, yes. The fact that he has directed three of Ricky Jay’s stage shows does not get discussed particularly often.

Bernstein: Right. Really all of his major shows.

Marlow: How is their collaborative process? Ricky Jay came to acting in an indirect way. In talking with David Mamet, is his initial attraction in casting him clear? I suppose it is somewhat the same attraction that you have in using him as a subject for a documentary.

Bernstein: Right. He saw him initially as performing magic. Ricky tells the story which, I think, is really indicative of his talent and also of their relationship. Ricky had never acted before. He performed a lot as a magician but he had never played a role in a movie. Shortly after he met Mamet, Mamet was teaching an acting workshop at NYU and asked Ricky to come and give a class. Ricky said, ‘How could I give a class? I know nothing about acting.’ Mamet said, ‘Everything you do is acting.’ That is really what started Ricky’s career, in a way. Mamet cast him and then other people cast him. I think there is a very powerful persona that is communicated when he is performing on stage or in a movie or in real life. That’s why, to him, he wasn’t necessarily perceiving the charisma that we perceive on the screen as ‘acting’ but, in some ways, I think that’s what it is.

Marlow: One of the interesting things about his books is that you get a sense of his taste as a historian of the art of performance and magic [and magic performance]. But seeing the footage of him as a child, when he was known as Ricky Potash, along with the photographs that you have of Max Katz and much of the material dealing with the influence of Slydini and Cardini and other folks who truly shaped his career as a magician is rather amazing. As filmmakers, you are able to carry that through to the end with Ricky Jay’s influence on another generation of magicians. When you were first thinking about making this film, at what point was it clear to you that you had to show how he arrived at this point and then where he is taking this experience?

Bernstein: Really early on. Beginning with ’52 Assistants,’ there’s actually quite a bit of history that he weaved into the performance, if you recall.

Marlow: I recall.

Bernstein: That’s part of what I found particularly fascinating about that show and his performance in general. The way he really does bring characters and the history of his art to life in an incredibly entertaining and absorbing way. He makes you feel like you really should know this stuff about these individuals that are very obscure to most people. But when he pulls you into that world, it’s incredibly alluring and fascinating. It was that and then the New Yorker profile, as we talked about, which had a lot about his history in the art. Both for me and Alan, that was really our interest. Delving into that history, which was so unique but also very flavorful and entertaining. Also, I would say that focusing on this mentor story, in particular, and following Ricky’s specific lineage as basically the story of the film came very early on in the process and largely came from him in that it was clear that he was much more comfortable talking about that than himself, directly. Or that was a way for him to talk about himself that he was really interested in doing. He wanted to pay tribute to these guys. He loves them. He thinks they’re amazing. He’s very enthusiastic about them (as I hope you sense in the film). It was a really good way to focus on both the history but also his life in a way that I think was better than a straight‑on biographical approach. ‘He was born here and he did this, blah blah blah.’ That’s why we did that. Also, because he is such a great storyteller, we wanted it to be told largely through his stories.

Marlow: I think it is a very smart strategy. If you have someone who is a natural orator in that way, you want to rely on that person as much as possible to tell the story. He’s definitely the best person to tell those stories and to generate interest in them. Perhaps this doesn’t play a role in the bigger scheme but the documentary shares the name of his consulting company. The tagline for that company is, ‘Arcane knowledge on a need‑to‑know basis.’ It seems as if, by the end of the film, you’re making it clear that if you’re watching this documentary expecting that he’s going to show you how these things are done, that’s not what this is about. It’s not about getting behind the illusions but dealing with how folks can be fooled, the history of sleight-of-hand and close-up magic. At least in my experience, what was interesting about ’52 Assistants’ is having folks on the stage where they’re experiencing at close range exactly what he’s doing. Even then, it doesn’t help you. It doesn’t make it any easier to understand how you’re being tricked.

Bernstein: Right. Exactly. I think it’s really great that you can have a whole history of sleight-of-hand without really knowing what it is (if you’re thinking about it in that way). Again, you don’t need to know what it is if you’re a spectator or an audience member or someone who is enjoying it. I think there are few arts that you would portray in that way without really talking about the method at all, specifically. That was a challenge.

Marlow: Any film with a gestation period of a decade or more….Obviously, you’ve been working on other things in the meantime. How has the experience been when taking the film out to festivals? And with Kino Lorber distributing it, I am certain that it is very rewarding to be at the stage where you can finally share the film with audiences. Now other people are inspired in the same way by the results of the film.

Edelstein: It has been a great experience. When you work on something this long, you forget that maybe something could actually come of it. If you get to work on something day-in and day-out or even over months off-and-on… Getting it out into the world is very different and, to some extent, a little bit disorienting. It did happen quite quickly. We had a pretty finished rough cut that was accepted by the New York Film Festival. We really had to scramble to get it completed in time for the festival. And then it takes on a life of its own. In our case, it’s been a very gratifying one because the response has been great and Ricky was very pleased with the film. We’ve been pretty gratified to have that kind of a response.

Marlow: Was it difficult to locate some of the television appearances as a boy and the early part of his career? I’m not used to seeing him with long hair, for instance. He’s a very different kind of character in his performances in the seventies than today.

Bernstein: It comes from varying sources. Actually, a lot of that early stuff of him in his hippie phase came from Dick Cavett, which was really great. He was hugely helpful, basically giving us the use of footage because he loves Ricky. He knew a lot of the guys. He had them on his show. He was really supportive of the project, which was great. The childhood stuff came from Ricky directly. That actually came quite late in the process. I think that was a mixture of him not really knowing where it was and not having it transferred but I think, once we passed a certain test of him feeling that he really trusted us, that’s when he started handing things like that over. It was gradual. But it was great. It was so exciting when he would find stuff and give it to us.

Marlow: That is also the case with the materials, like some of the posters and other artifacts that that he has in his collection?

Bernstein: Yes, definitely. All of the early, pre-20th-century materials are from his collection. That was great in that he was very forthcoming with these materials. None of that was… It’s not as personal. He’s personally connected to it in that it’s part of his collection, which he’s very passionate about, but it wasn’t things that no one has ever seen. I don’t think his wife had even seen that childhood footage. He dug it out for the documentary. He doesn’t have a lot (even though he’s an amazing collector and archivist) on the subjects that he focuses on. He doesn’t really have very much about himself and what he does have isn’t stuff he looks at often. It’s just tucked away. Which surprised us, initially. We thought, ‘Oh, he must have a lot of these things,’ that we ended up getting out of the old magic periodicals, like those photos of Slydini teaching his grandfather and businessmen around the table. Those kind of things Ricky didn’t have. We found those. We researched and found that stuff. That was a surprise for us and, I think, really fun for him, too, when we’d discover this stuff that he maybe had seen as a kid but really didn’t remember. It was fun for him, I think.

Marlow: You mentioned the participation of Dick Cavett. In addition to his contribution of footage, he is the narrator of the documentary as well. You use him somewhat selectively which I think is rather wise. Did he offer up the materials as a result of your approaching him as a narrator or did he offer up being a narrator as a result of the request for materials?

Bernstein: Actually, he was very helpful with footage early on. It wasn’t until the very end that we had the idea, ‘Let’s ask him to narrate.’ He was delighted to do it.

Marlow: He’s very effective. I cannot think of anyone better.

Bernstein: I think he’s perfect for that.

Marlow: One final route of inquiry. Bob Dylan has an association with the soundtrack. I knew that Ricky Jay had appeared in a video of his and was involved in an audio book project that was related to ‘Ricky Jay Plays Poker.’ How did he become involved in the documentary?

Edelstein: I don’t mind answering, I’m just not one hundred percent sure what the answer is. They know each other. They’re friendly.

Bernstein: Dylan is a fan, I would say, of Ricky’s.

Marlow: Yes?

Edelstein: Yes.

Bernstein: It’s mutual.

Edelstein: If you know Dylan’s music well, he has had a longtime fascination with gambling and unusual Americana, that kind of thing. Ricky certainly shares that interest and probably knows a great deal more about it. I think, on that basis, there was a lot of shared interest.

Marlow: Was it Ricky himself who said to you, ‘Dylan may be willing to put a song in here…’ or something else altogether?

Bernstein: It was actually Dylan’s manager. Jeff Rosen is a good friend of Ricky’s manager. He was helpful to us when we were trying to raise money. He’s a big fan of Ricky’s and a friend as well. We got the idea, ‘It’d be great to use a Dylan song here,’ and he said, ‘Sure.’ He was very helpful with that.