In documentary, as in writing, the profiles far outnumber the portraits. It’s no wonder: whereas the profile trades on the credibility of its subject, making it a rare safe bet for producers and programmers, the portrait develops out of the intensity of one gaze meeting another. Documentary profiles typically sink or swim on the quality of their archival footage and interviews; sometimes useful as historical thumbnails, their rise-and-fall plotlines and commercial tie-ins often result in an unshakeable dissonance with the ostensible radicalism of the subjects. The documentary portrait, on the other hand, sets out to encounter life rather than outlining it. Several films at the recently concluded Toronto International Film Festival that are perhaps headed to film festival stops elsewhere shed light on the precariousness of this operation.

Manakamana observes pilgrims riding a funicular to and from a Hindu temple in Nepal, though this context is never explicitly stated. Co-directors Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez adapt a structuralist strategy for the film so that each stationary shot lasts the length of the ride (about the same, fortuitously, as a roll of 16mm film). The funicular thus prescribes both the frame’s duration and composition (chest up, with the same startling intimacy that comes of sitting across from a stranger on any public transportation), but both aspects are colored by the sitters themselves. Two musicians effortlessly bend time as they play a beautiful melody on their sarangi, for example. Each portrait is bookended with the carriage being swallowed into a loading dock, the sheltered space darkening the image and amplifying the already vivid sync sound. We know a cut is being made in the darkness, and yet the timing still affects a magical fluidity so that each configuration seems a kind of rebirth.

As with other work produced out of Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab (Leviathan co-directors Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel are listed as producers here), the film is designed to reinscribe the viewer in a kind of face-to-face encounter, trading some measure of authorial control for heightened presence. Still, while the film eschews all exposition in approaching pilgrimage as an actuality, Spray and Velez’s canny assemblage undoubtedly mediates our understanding of the film’s subject. We progress from villagers to metal-heads busy documenting themselves, English-speaking visitors, even a carload of goats. If these selections feel somewhat dutiful in their repositioning of the ethnographic subject, the film generates a more organic form of excitement as the different sitters begin to echo one another in their commentary on the landscape. “The hills are so big” is a common refrain, but one that means different things to each speaker; strung together these free associations finally blossom into a prismatic rumination on the experience of landscape.

One can’t get much further from Manakamana’s studied lack of agenda than Chris Marker and Pierre Lhomme’s Le Joli mai (1963), a probing work of auto-ethnography in which portraiture figures as a form of intervention (it showed in a stunning digital restoration currently on tour). Following on the heels of Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s breakthrough Chronicle of a Summer (1961) and presaging Godard’s aggressive interviews in Masculin Féminin (1966), Marker and Lhomme draw upon the rudimentary tools of Direct Cinema to forge a kaleidoscopic portrait of Paris in May 1962 (“the first spring of peace” following the Algerian War). Marker and Lhomme pursue the sociological implications of the new lightweight cameras and sync sound recorders, as a means to cross social boundaries of class, race, age, and private property.

Woven together by one of Marker’s characteristically poetic voiceover texts, Le Joli mai’s networked interviews exemplify dialogue and dissension even as the individuals being interviewed all too often tend towards apathy and alienation. A strong shaping hand is evident in the sequencing of these encounters: the variations of complacency found in the first half wither under the glare of the testimonies of an African immigrant, a young Algerian man and a former priest who gave up the church to work as a labor organizer. If each of these latter figures seems better defined, living closer to the truth, than the hazy or mildly idiosyncratic citizens of the first half, the film leads us to understand that this has everything to do with a tragic awareness of the vicissitudes of identity. Not for the last time in a Marker film, authority is ceded to those who have none.

The unrelenting nature of Le Joli mai’s interviews evinces clear disappointment in the subjects’ answers without reducing them to sociological abstractions. The young couple questioned by Marker just before the film’s intermission, for instance, insists upon remaining aloof from all public affairs even as the young man prepares for his deployment in Algeria. Marker’s questions become more pointed and exasperated, but he never presses his advantage as the filmmaker by making a cutting edit. The young couple’s failings, all too emblematic of their society, are allowed to stand on their own. “People exist with their complexity, their own consistency, their own personal opacity,” Marker wrote, “and one has absolutely no right to reduce them to what you want them to be.” Of course this cuts both ways in Le Joli mai, for just as Marker and Lhomme generally refuse to caricature their subjects, they also don’t let them caricature themselves. By transcending their own ostensible roles as the “man on the street” interviewer who readily accepts and even encourages predigested answers, Marker and Lhomme challenge their subjects to examine their own statements. The interviews are portraits, finally, of the moment when the mask begins to slip.

Claude Lanzmann’s The Last of the Unjust (now at the New York Film Festival) is an addendum to Shoah (1985) and in some ways its antithesis. The film concerns Benjamin Mumelstein, the final president of the Jewish Council in Theresienstadt (the “show” ghetto used by the Nazis for propaganda purposes) and the only appointed “elder of the Jews” to survive the war—proof enough of his complicity in the eyes of many survivors. Lanzmann found Mumelstein living in Rome in the 1970s and persuaded him of the importance of his testimony. In spite of the obvious historical interest of their interview, however, Lanzmann omitted Mumelstein from Shoah’s tapestry. Why? Partly, one imagines, for simple reasons of length, as Mumelstein’s charisma and complexities demand an attention span superseding even Shoah’s extended interviews. Perhaps more to the point, Mumelstein’s ill-defined position as a Jew who had some degree of agency during the war does not fit neatly into Shoah’s structure of Jewish victims, who Lanzmann compels to remember; Polish collaborators, who, not unlike in Le Joli mai, Lanzmann compels to reveal themselves; and the Nazis themselves, who Lanzmann must film without their knowing (the journals of Adam Czerniakow, the Jewish leader of the Warsaw ghetto, are read by a historian, providing a powerful but disembodied link to this same contested terrain). Mumelstein must have presented a challenge Shoah’s form in other ways as well: where Lanzmann’s film strips away outside reference points, for instance, Mumelstein consistently peppers his testimony with literary allusion and metaphor.

All of these complications evidently proved vexing even to the famously willful Lanzmann. The Last of the Unjust begins with a dense introductory text, in which the director allows that the interviews with Mumelstein haunted him for many years and that it was difficult for him to finally accede to posterity. This in itself seems surprising given the conviction with which he commanded victims and collaborators alike to testify for his camera, though it’s not nearly as striking as his decision to show artwork and an archival Nazi propaganda film from Theresienstadt in The Last of the Unjust—a definitive reversal of his former prohibition against using archival images to represent what Dori Laub called the “event without witnesses.”

One wonders if Lanzmann’s decision to relent in permitting the archival images wasn’t at least in part a product of a complex identification with his subject (given the psychological intensity of their encounter, one is tempted to describe it as a kind of counter-transference). Several critics have commented on the film’s actually being a double portrait of Mumelstein and Lanzmann, but it’s worth lingering on the surprising parallels between the two. In recounting his methods for keeping the ghetto running, Mumelstein revels in an obsessive attention to detail, so much so that Lanzmann interrupts him to remind him of the horrific context of his actions. The irony is that the Lanzmann of Shoah often seems equally obsessive about understanding the Holocaust in terms of its blunt mechanisms (the train schedules being the paradigmatic example).

Mumelstein also matches Lanzmann’s exacting attitude to epistemology. So much of Shoah is concerned with the question of who knew what when, and here we have Mumelstein subtly correcting Lanzmann saying that Theresienstadt Jews were sent to Auschwitz to imply that at the time he only knew they were going to “the east.” This correction can easily be read as an unwillingness to accept the truth, but, as Lanzmann points out in his introductory text, Mumelstein also seems incapable of dishonesty. Pressed on this issue of not knowing about the concentration camps, for instance, Mumelstein allows that he met other Jews—from Denmark, for instance—who seemed to already know about the camps and the showers, and in so doing allows the possibility that he could have known as well. It would be so much easier for him to simply claim that no one knew anything at the time, but Mumelstein, like Lanzmann, has a passion for accuracy. What can it mean for Lanzmann, a diehard defender of Israel, to identify with a man who never visited the Jewish homeland for fear of retribution? Viewed from the distance of thirty years, their interview seems as much about personal identity as historical trauma.

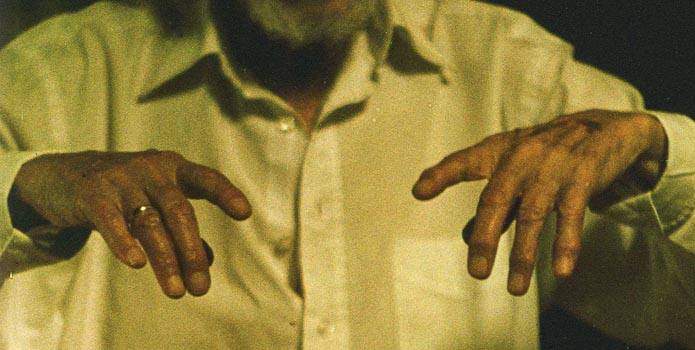

There were several other fascinating portraits on view in the experimental Wavelengths section at Toronto, but none so invigorating as Robert Beavers’ aptly titled Listening to the Space of My Room. Imagine someone boiling down all the impermanent sensations, routines, memories, and emotions that make a home a home into an intensely flavorful reduction, and you begin to understand Beavers’ stunning film. He and his housemates are crystallized at work: the camera sways with the hands of an older man bowing his cello; observes an older woman tending her garden from inside the darkened house; mirrors Beavers himself examining individual frames of film to stage his somatic cuts. The intricately interlaid tracks of sound and image do not abide any standard measure of continuity, and yet there’s something immediately comprehensible in this exquisitely tuned song of the body in space.