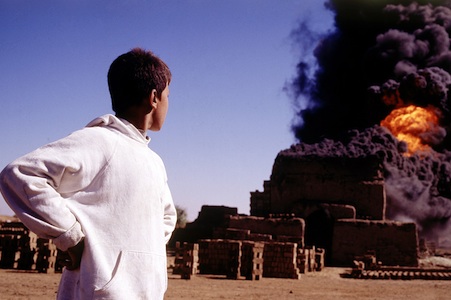

James Longley’s Iraq in Fragments and Laura Poitras’s My Country, My Country, made in 2005 and 2006 respectively, remain two of the very best documentaries on the Iraq war. Unlike most other documentaries centering on the war, these films strayed away from the thick of the fighting, destruction and IEDs to focus on the country’s “everyday” people.

So much has happened since. Amidst the bombings and continued fighting, an elected Iraqi government took office. And more: a troop surge. Abu Ghraib. No weapons of mass destruction found. Operation Augurs of Prosperity. More bombings. A new U.S. president. Further elections in Iraq in 2009. Still more bombings. The last of the American troops leave in August, 2010. In these times of the immediacy of cell phone cameras, YouTube and the 24-hour news cycle, and when news from Iraq no longer plays a starring role in the daily headlines, one may understandably feel these films have become simply historical. But like the best current events documentaries, or like a great historical film or novel, these two films remain fresh and relevant.

Longley’s portraits of an 11-year-old auto mechanic in the mixed Sheik Omar neighborhood in the heart of old Baghdad whose father is missing, followers of the Shiite political/religious movement of Moqtada Sadr and Iraqi Kurds eyeing an opportunity for their independence provide rich, unique characters. In a past interview Longley said, “The most important thing is the element of having enough time to spend with the people you’re filming, and knowing from the beginning that you’re going to spend a lot of time with them, and that you don’t have to rush to get your material. You can relax, sit back and have lunch with people, have tea with them, get to know them at a very leisurely pace and explain to them what you’re doing and clear up any questions and concerns that they might have with your project as you go along.”

Laura Poitras spent eight months in Iraq shooting My Country, My Country and created an equally intimate portrait of Iraqis living under U.S. occupation. Her principal focus is Dr. Riyadh, an Iraqi medical doctor, father of six and a Sunni political candidate. An outspoken critic of the occupation, he is equally passionate about the need to establish democracy in Iraq, arguing that Sunni participation in the January 2005 elections is essential. Yet all around him, Dr. Riyadh sees only chaos, as his waiting room fills each day with patients suffering the physical and emotional effects of ever-increasing violence.

Poitras wisely chose to have the film unfold as a narrative. Now at work overseas on a new film, she comments, “Storytelling should always reach a different level than the particular focus of a film, book, play, etc. Good stories provide a greater truth about the human experience. Documentaries, even though they are grounded in reality, are no different.” In pursuing our personal human experience we turn back to these people, re-immerse ourselves in their culture, wonder what has become of them, look back at the facts of the events and become angry, concerned, want to act locally.

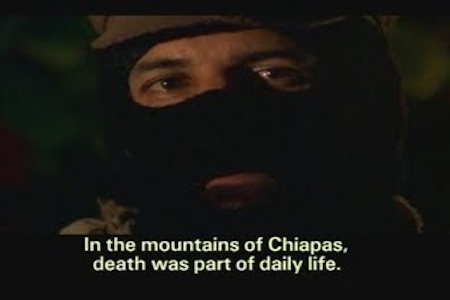

One can be inspired similarly with documentaries’ whose at-one-time current topic no longer appears in the headlines or cable TV news. For some, Nettie Wild’s acclaimed 1998 documentary A Place Called Chiapas, which covers the uprising of the Zapatista National Liberation Army, whose personnel were made up of impoverished Mayan Indians from the state of Chiapas and who took over five towns and 500 ranches in southern Mexico in battles with the government that resulted in 145 deaths, may not seem as relevant. An uneasy truce took place in 2003, and Chiapas now is touted as a destination tourist spot. Yet for the story and the characters Wild’s film remains enthralling. “It was never meant to be a current events documentary,” Wild explains. To begin with, “by the time it came out it was a good year since I started shooting. If I were just there to cover the events I’d wonder what the devil I was doing, as the most up-to-date news would beat me to getting anything out. You need the time to research. It takes time to get to know the people, get under their skin, and then it took eight months to edit.” Like Poitras, Wild sees the importance in telling a story. “To keep the audience on the edge of their seats, I go straight to the center of the contradiction, and therein lie the conflicts the characters are living through. If you tell it well, the audience will be pulled into the story.” And besides, she adds, “If I want to learn about current events I’ll just go to YouTube or Wikipedia.”

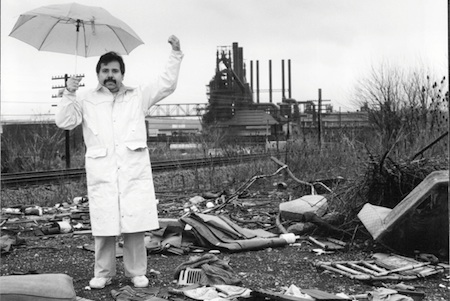

Tony Buba’s 1988 ahead-of-its-time feature/documentary hybrid Lightning over Braddock: A Rustbowl Fantasy chronicles the decline of Braddock, Pennsylvania, a hard-luck town which once flourished as “Pittsburgh’s shopping center.” Amidst this backdrop a director (Buba, playing himself) tries, without much success, to make a movie with a crazy street hustler named Sal, who considers himself responsible for Buba’s modest success. While the real-life Buba was (and remains) concerned for the fate of his hometown (he had previously made a number of short films about Braddock’s many eccentric characters, including Sal), he had not set out to simply document the city’s decline. “I was conflicted as filmmaker in profiting from the town’s troubles,” says Buba. “I just wanted to push the envelope more on documentaries and wanted the audience to question what I was doing in making a documentary with the mills closing. You want people to experience that question and start a dialogue going.”

Buba’s unique, seamless mix of fiction, non-fiction, memorable characters, humor and pondering make for a timeless film, but more recent developments—from Levi’s “Ready to Work” ads that featured Braddock residents taking pride in their town to the devastating 2010 closing of the Braddock Hospital (that happens to be the subject of a documentary Buba is currently at work on)—have helped maintain an interest in the film. More recent economic events haven’t hurt, either. A 2012 screening at Anthology Film Archives in New York brought a full house and a new perspective in the wake of the 2008 Meltdown. “It’s the cyclical nature of history,” muses Buba. “The problems persist despite liberal good intent.”

Indeed, our culture’s ailing to learn from past mistakes also helps render documentaries timeless. Peter Davis’ Hearts and Minds, the controversial 1975 Oscar winning documentary about the Vietnam War exposes the same lies, attitudes and mindset of the U.S. government that helped provide the setting for the Iraq that Iraq in Fragments and My Country, My Country take place in. In How to Fold a Flag, Michael Tucker and Petra Epperlein, whose Gunner Palace is one of the first and best documentaries of the Iraq war as experienced through the eyes of U.S. troops, follow some of these same soldiers as they return home and restart their civilian lives to varying degrees of success. (The film also looks at the family of one soldier who didn’t make it back alive.) While one runs for U.S. Congress, another is dealing with PTSD. Another is working at hog processing plant at night while relying on the GI Bill to pursue a career. For all of these soldiers, they are haunted by memories of a difficult, uneasy experience fighting in a foreign land—and for many of us that may feel a little too familiar.

And so it goes. “This is not Vietnam,” Dr. Riyadh complains to U.S. military officers after they’ve taken Fallujah in My Country, My Country. Unfortunately, history challenged his assumption. Fortunately, we have filmmakers who create intimate, complex portraits of people whose struggles to transcend what is happening around them, stand up for what they believe in, or at the very least maintain a dignity and sense of pride (no matter how difficult that may be) are people we can have tea with as often as we want, no matter that the conflict has ended. Let us begin to learn from our mistakes by learning from them.

Brian Gordon has spent twenty-plus years in the film festival world, primarily as the Golden Gate Awards Director at the San Francisco International Film Festival and Artistic Director of the Nashville Film Festival. Currently based in Manhattan, Brian works with filmmakers and festivals and serves as a Documentary Programming Associate for the Sundance and Tribeca Film Festivals and the PBS series POV. He has recently begun his newest assignment as Senior Film Programmer at the Gold Coast Arts Center where he oversees programming for its ongoing film series and the Gold Coast International Film Festival taking place in October. He has lost track of the number of documentaries he’s seen.