“We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces.”

—Norma Desmond, Sunset Blvd.

You say that you’re really into old movies and you can’t get enough of the classics but you just haven’t found a way to love silent cinema? You say that all your friends are doing the silents and you feel left out? You say that you too want to be part of the early cinema crowd but just haven’t found your way to loving the movies before sound?

Even among many classic cinema buff, silent movies can appear alien and unfriendly, a duty more than a treat. And it shouldn’t be that way at all. In their day, silent films were a universal entertainment, a truly popular art that transcended language and culture.

There are those who think of silent films as primitive and naïve. Some were, to be sure, but movies grew up quickly in those early years. Those primitive experiments and one-shot gags matured into feature films in under two decades, and the knockabout slapstick comedies of the Keystone Kops gave way to the comic grace of Charlie Chaplin and the invention of Buster Keaton just a few years.

And then there’s those scratchy, poorly-preserved prints that were often presented at wrong projection speeds that made everything look sped up and absurd. It’s hard to appreciate let alone recognize the scope and technical wonder of the silent extravaganzas under such conditions.

Thanks to the efforts of film preservationists, a new spirit of cooperation between international film archives, and new digital tools, those days are fast disappearing. Silent cinema is getting a makeover and audiences are finally getting a chance to see the glamor and splendor that original audiences saw when they went out to the flickers.

There is a universe of films, genres, moods, sensibilities and styles to be discovered in the thirty-plus years of cinema before the introduction of sound changed the way films were made and experienced. This isn’t necessarily a list of the greatest or the most important silent films (though there are some of both sprinkled through), but rather a selection of the most entertaining and engaging films of the era. Consider it a place to start your appreciation of the glory and grandeur that was the cinema before sound.

A Trip to the Moon (1902, Georges Méliès)

You want to get an idea of how lavish and creative the so-called primitives could be? Magician-turned-filmmaker Georges Méliès was a pioneering special effects artist and a fantasist with an unbound imagination, but more than anything else he was a showman and A Trip to the Moon is his most ambitious spectacle. Thanks to the painstaking restoration of the sole surviving hand-painted print of the film by Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange, we can now see what enthralled audiences at the turn of the 20th century: a picture-book fantasy brought to life as a work of pure, playful imagination with crazy special effects and delirious color. Accompany this with a screening of Martin Scorsese’s Hugo (2011) and you might just come away with a new appreciation for the early years of filmmaking. And if this inspires more interest in the pre-feature era of filmmaking, try the fantasies of Ferdinand Zecca and the work of Alice Guy-Blaché, the most versatile filmmaker of her era.

Juve vs. Fantômas (1913, Louis Feuillade)

While D.W. Griffith was busy advancing the art of cinema storytelling through editing in the U.S., Louis Feuillade was expanding the possibilities of tableaux filmmaking, packing his single-take scenes with energetic movement, complex compositions and narrative surprises. Feuillade’s Fantômas films are pulp adventures by way of surreal crime fantasies featuring the cinema’s first supervillain and they are both archaic and strangely modern in style, pace and imagery. Juve vs. Fantômas is the second chapter of a five-part serial but each section is a self-contained adventure and this chapter is as crazy as it gets: there are secret passageways, elaborate disguises, mad ambushes and a centerpiece train wreck. You can see why Feuillade was a hit with the surrealists and the everyday filmgoer: he pulled out a surprise at every turn. If you like this, by all means go on to Les Vampires (1914). It’s even wilder.

Sherlock Jr. / The Playhouse (1924/1921, Buster Keaton)

While The General (1926) is considered Keaton’s greatest film and Steamboat Bill Jr. (1928) is my personal favorite, Sherlock Jr. is his most conceptually ingenious movie. Playing a cinema projectionist who takes a logic defying leap into the silver screen, Keaton toys with the very nature of cinema as he interacts with the film-within-a-film reality and then bends the logic of his own reality when he turns master detective. What a marvel of technical virtuosity (accomplished with nothing but a camera and state-of-the-art engineering equipment for 1924) and comic invention! It’s a short feature so I’ve paired it with Keaton’s most ingenious two-reel comedy: The Playhouse, which begins with Keaton playing every role (including the audience) in a vaudeville act and proceeds to dismantle our sense of reality at every turn. And Keaton even breaks out of the stone face persona to play a chimpanzee: with simple make-up, rubber-faced gestures and a make-over created entirely from body language, he offers the greatest impression of a simian that a mere human has ever put to film. But then, of course, Keaton is no mere human.

The Black Pirate (1926, Albert Parker)

Adventure spectacle, early Technicolor splendor and the beauty of Douglas Fairbanks—the first action hero and the original movie superstar—in action, this may be the most exhilarating of silent movie adventures. It’s quite the swashbuckler, with the acrobatic Fairbanks leaping, lunging, charging and dueling his way through the world of high seas criminals and it packs in every classic pirate movie convention, from saber duels to walking the plank. Fairbanks made a specialty of bringing all-American energy to every character he played and he made audiences believe he was having the time of his life while he executed the most spectacular stunts seen on the silent screen. He probably was at that. As an added spectacle, this is the rare silent film shot in the early two-strip Technicolor process, which has the texture of handpainted vintage postcard. It only adds to the vintage beauty of this old fashioned swashbuckler with jazz-age attitude.

Spies (1928, Fritz Lang)

Fritz Lang brought myth to life in his epic Die Nibelungen films (Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge) and imagined the future with unprecedented scope and scale in his allegorical science fiction classic Metropolis, but his visually inventive, breathlessly-paced pulp thriller Spies is surely his most purely entertaining film of the silent era, and perhaps of his entire career. It’s like a James Bond thriller in the twenties, complete with a criminal mastermind who runs a literal underground espionage network with a vast surveillance and communications apparatus wired throughout the city, a small army of flunkies, and an arsenal of high-tech gadgets. Lang packs enough intrigue, double dealing, secret identities and criminal conspiracies for an entire serial into one wild feature film.

The New Gentlemen (1928, Jacques Feyder)

If you think that silent movies are naïve and quaint, you haven’t delved into the wealth of worldly films that blossomed in the late 1920s. This is one of the best, a deft comedy of manners that pits an idealistic labor organizer against a career politician with old money and expensive tastes. What begins as an underdog battle of wiles in love and politics, however, slips effortlessly into a knowing satire of class and power in the lively culture of France in the 1920s. Jacques Feyder directs a cynical subject with a gentle compassion for the follies of love and life and offers a snapshot of life in all levels of society in Paris along the way. This is the height of European sophistication in silent moviemaking. The details are exotic but the foibles of human nature recognizable in any culture.

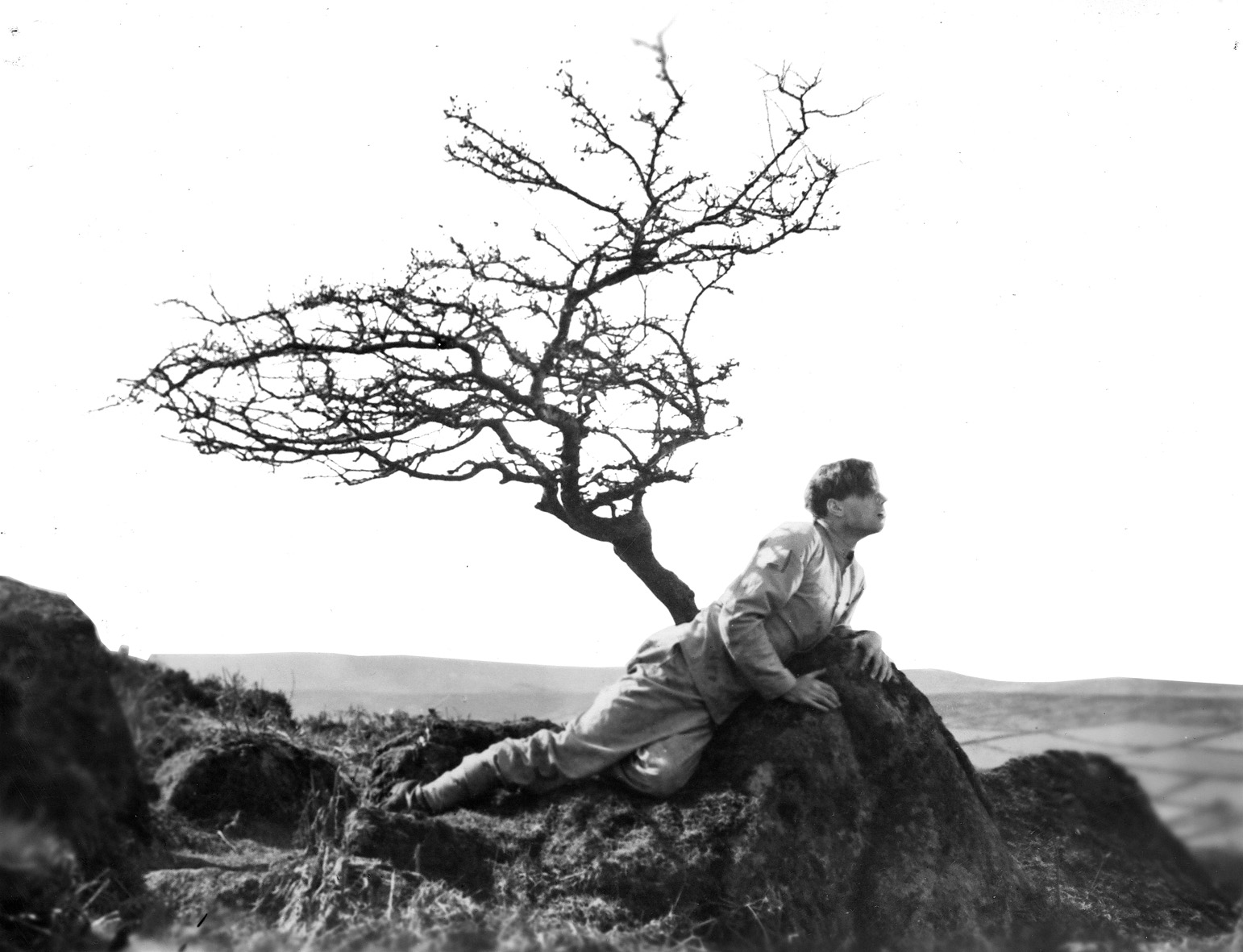

A Cottage on Dartmoor (1929, Anthony Asquith)

Before Alfred Hitchcock was crowned the Master of Suspense, the smart money might have been on Anthony Asquith to take the title on the basis of this film. In fact, Asquith never made another movie as visually dynamic or cinematically passionate as this engaging showpiece. It begins as a mysterious Gothic thriller playing out on the stormy moors, leaps into a lively flashback, and winds itself into a romantic triangle where emotions under pressure finally explode with a power beyond human agency, or so it seems. It’s as good as—and perhaps even better than—the best of Hitchcock in the silent era, with a style that draws heavily on German Expressionism and a sensibility with as much compassion and regret as mystery and suspense. This is one of the unheralded greats of the silent era.

Modern Times (1936, Charlie Chaplin)

Charles Chaplin, the filmmaker and actor, bid farewell to Charlie Chaplin, the iconic screen persona of the Little Tramp, with Modern Times, a silent film for the sound era. Made during the depths of the depression, the Tramp and his “Gamin” (a winning and very grown up Paulette Goddard) fight poverty, industrialization (in a hilarious assembly line burlesque) and even an omnipresent Big Brother in classic pantomime routines set to an inventive mix of sound effects, music and even a few words from the voices of authority, though never from the Tramp. The classic scene of Chaplin being wound through the gears of the factory machinery remains one of the most iconic images in film history: the little guy who manages not to get ground up in the machine. Chaplin accomplishes it all with comic grace and endearing sentimentality.

Sunrise (1927, F.W. Murnau)

I save the best for last. Subtitled “A song of two humans,” Sunrise is a deliriously romantic fable on a magnificent scale, directed by a German master with the full resources of a Hollywood studio at his disposal. The result is the most beautiful piece of cinematic poetry to come out of America, a story of tragedy and redemption in a culture that bridges rural idealism and urban excitement. Sunrise reminds us of the silent cinema dream worlds lost in the new realism and visual literalness of the sound revolution. Almost a century of sound filmmaking has never equaled its emotional power or the cinematic purity.