The more “disreputable” the film genre, the more easygoing fans tend to be toward that old argument of style vs. substance. Accustomed to rarely finding profundity, complex human interest or subtle plotting in their oft-critically-dismissed favorite cinematic niche (no wonder, since producers and studios know such qualities usually translate into lower commercial returns) those horror aficionados who don’t simply prize gore and body-counts above all else have learned to specially value directorial idiosyncrasy and panache.

In that regard there is probably no director more celebrated by horror fans than Dario Argento, the Italian auteur still active on the cusp of his 75th birthday. [Editor’s note: In fact, now out with an Indiegogo campaign for a new feature. Argento is interviewed on this project and other topics in an upcoming edition of Keyframe.] Actually, there are few more esteemed by the body-count/gore crowd as well: The absolute crux to his art is a voluptuous fascination with violent death, the portrayal of which often triggers his most baroque flights of cinematic imagination and high style.

Detractors have long quailed not only at his sadism, but also at his apparent disinterest in nearly all other basic elements of the horror thriller: Notably attention to plot logic, character complexity, performance, etc. Argento has admitted these things are of secondary interest to him, at most. He’s often been compared to Hitchcock, yet that late “master of suspense” enjoyed unsettling audience expectations only to inevitably “explain all” in clinical, orderly fashion, even as prosaically as the psychiatric analysis that demystifies all Norman Bates’ delusions at the end of Psycho.

Argento may often (however reluctantly) deploy such explicators to tie up loose ends at the close of his own screen murder mysteries. But one gets the sense he really doesn’t care “whodunnit” at all, and that each resolution might just as easily (and unconvincingly) gone in any other random narrative direction. He uses cinema not to spy on and catch a killer, but to become the “sick” embodiment of homicidal insanity itself. Many thrillers are filled with “red herrings,” but few so frequently let the camera fib as Argento does, misleading us with fetishistic close-ups or point-of-view shots that may ultimately bear no concrete relationship to what a fictive perpetrator might be doing or seeing. They exist simply as part of an aesthetic whole designed to disorient and disturb.

Perhaps, his supporters argue, we shouldn’t pick at the extent to which Argento’s films fall short of making conventional “sense,” but rather wonder why he even makes a halfhearted effort thataway at all. “I work in a surrealistic way, like being in a trance,” he told Maitland McDonagh in a short interview printed at the end of her excellent book Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds: The Dark Dreams of Dario Argento. “When I finish a picture I’m always surprised by the things I see. It’s like automatic writing, as though someone else suggested ideas. Like a schizophrenic.”

The son of a film producer and a well-known photographer (a strong antipathy toward the latter purportedly shaping the many harmful mother figures in his movies), Argento grew up well familiar with the industry he’d first enter indirectly as a daily newspaper critic, then as a young scenarist. In that role he contributed to several standard genres of the Italian film biz’s biggest boom decade, including sex comedies, crime pictures, war dramas, and “spaghetti westerns.”

Along with another up-and-comer, Bernardo Bertolucci, he was given story credit on that last category’s crowning popular epic, Sergio Leone’s 1968 Once Upon a Time in the West. But when it came time for his own directorial debut, he preferred the realm of macabre suspense that had enthralled him since a rather sickly childhood, and which had become the signature Italian film as well as pulp-literary form known as “giallo.” (I.e., “yellow,” after the color originally sported by mass-market paperback thriller covers.)

Mario Bava, whose own fantastical, morbid and stylish bent as a director would greatly influence the younger man’s evolving sensibility, had pioneered the screen giallo, most notably via 1964’s sleekly gorgeous proto-slasher Blood and Black Lace a.k.a. Six Women for the Assassin. By the end of the decade, international screens were full of eccentrically titled Italian murder mysteries in which beautiful people were serially slain by elusive predators in glamorous settings and various states of undress.

Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) gave the subgenre a further boost. Even those critics who dismissed its script (actually one of the writer-director’s more cogent ones) as a nonsensical excuse for violence admitted that in terms of camera choreography and setpiece design, he merited the immediately-affixed “Italian Hitchcock” label. Imported star Tony Musante played an American writer who witnesses an attempted murder, then is helpless to stop the maniac’s repeated attacks on himself and others.

With its deluxe packaging (Bertolucci d.p. Giuseppe Rotunno’s widescreen images, Leone-famed composer Ennio Morricone’s score), Bird was a work of undeniable assurance, as well as a global hit. Somewhat less so were two next-year followups very much in the same vein, The Cat o’ Nine Tails and Four Flies on Grey Velvet. If anything, they were even more strikingly stylish (particularly the comparatively under-seen Flies), though Argento’s escalating indifference to narrative coherence got him accused of purveying mindless cruelty. It was a charge that would never really go away.

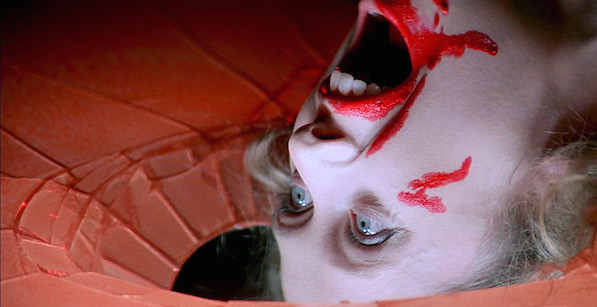

After attempting to mix it up with a period comedy intended only for Italian audiences (but even they didn’t like critically trashed Five Days in Milan), he returned to the internationally-cast giallo thriller model. But 1975’s Deep Red was a quantum leap into perversity that made his prior efforts seem comparatively formulaic. An English jazz musician (Blow-Up’s David Hemmings) witnesses the death throes of a psychic attacked after she’d sensed the presence of a serial murderer at a public event. Said killer goes on a rampage killing anyone who might’ve caught on to his or her evil doings.

This faceless, elusive, raspy-whisper voiced villain forever just out of frame was already a genre cliche (though that didn’t stop Argento from deploying identical figures in the future). But the film’s bold, bloody setpieces were as riveting to audiences as they were repugnant to censors. Deep Red became one of the most frequently, drastically cut movies in a filmography that’s consistently suffered the “death of a thousand cuts” (when not outright banned from release) in territories around the globe.

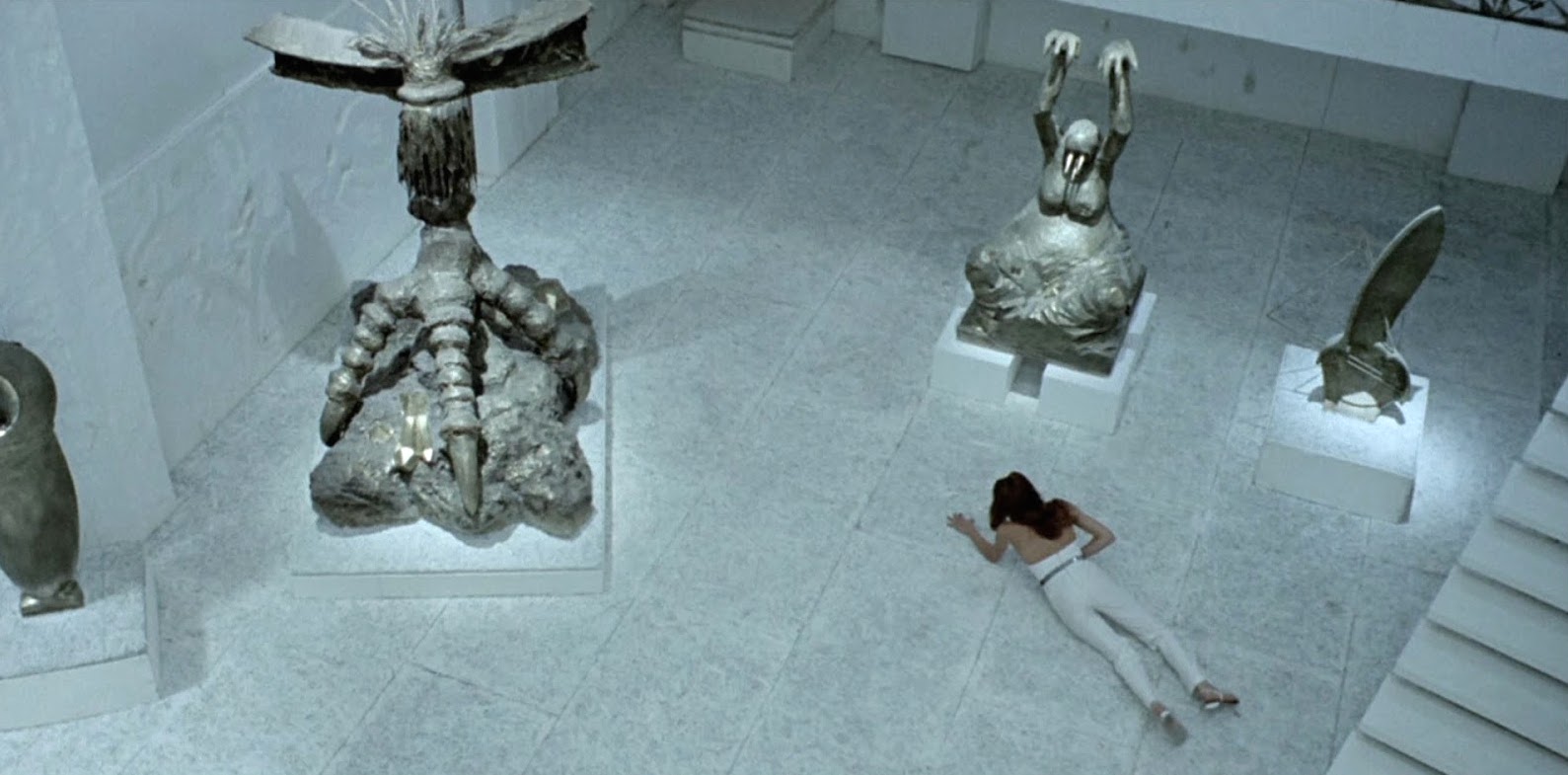

From this major commercial success Argento moved on to an even greater one with the film he’s still most widely known for, 1977’s Suspiria. This supernatural fantasmagoria tossed an American student (Jessica Harper) into a sinister German ballet academy that turns out to be controlled by witches. Freed from any last vestige of realism in storytelling or presentation, Argento let it rip in a hallucinatory onslaught of overwhelming production design, saturated colors, thunderous prog-rock (by the Italian combo Goblin) and extreme violence.

It was a sensation, prompting him to leap into sequel-of-sorts Inferno, another tale of witchery. But almost incredibly, this equally out-there enterprise was denied U.S. theatrical release, ostensibly because its plot was utterly impenetrable. (An alternate explanation goes that major management changes at 20th Century Fox during production left the finished film without any remaining supporters at the studio; rather than see any credit go to their predecessors, they simply dropped the movie.)

Nearly all Argento’s projects seemed similarly beleaguered in one way or another from this point on, even as his cult among horror fans grew. 1982’s Tenebre, considered like Deep Red an apotheosis of the giallo form by many, was dogged by the director’s fights with star Anthony Franciosa and by extensive, damaging cuts in many markets. (An uncut version wasn’t approved for U.K. release for another two decades.) Three years later Phenomena a.k.a. Creepers proved a wacky mix of supernatural and giallo elements, with teenaged future Oscar winner Jennifer Connelly as an American movie star’s daughter dumped Suspiria-style at a Swiss boarding school where her fellow students frequently seem to get murdered. As if that weren’t enough, our heroine is a telepathic sleepwalker who can control the insect world with her mind. And oh yeah: The villainess (Argento’s sometime offscreen spouse Daria Nicolodi, whom he frequently enjoyed killing onscreen) gets dispatched by a razor-wielding chimpanzee. You know, these things happen.

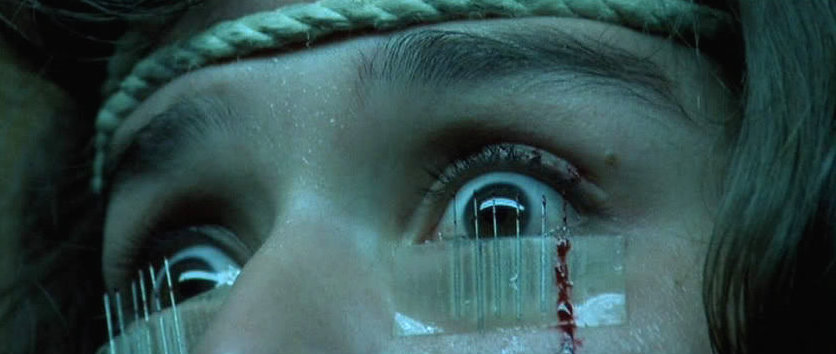

Amidst screenwriting/producing chores for equally horror-focused protégées Lamberto Bava (the admirably all-stops-out 1985’s Demons and its sequel) and Michele Soavi (1989’s handsome The Church), Argento made his most lavish film to date in Opera. But this gory tale of mayhem behind the scenes of a Verdi staging (the ever-ill-fortuned “Macbeth”) suffered its own parade of real-life disasters, from on-set difficulties to severely cut release versions in those countries where it was distributed at all. (It barely surfaced in the U.S. several years after its European premiere.)

Still, erratic and beleaguered as it is, Opera struck some as a return to the “old” Argento’s stylistic vigor and confidence, particularly when measured alongside his subsequent efforts. Uneven latterday giallos The Stendahl Syndrome (1996) and Sleepless (2001) have their supporters. But few rose to the defense of 1993’s desultory U.S.-shot Trauma. 2004’s low-budget The Card Player and the next year’s TV movie Do You Like Hitchcock? were atypically small-scale, restrained murder mysteries of minor appeal.

Generally preferring to invent his own material while borrowing ideas from many influences, Argento erred with two straight revamps of oft-told classic horror tales: 1998’s Phantom of the Opera and 2012’s Dracula 3D are widely considered among his weakest films. Wandering yea farther from terra familiar to direct a script by two American fans, albeit one that paid him explicit homage, he ended up regretting 2009’s poorly received Giallo. So did nearly everyone, since the film wound hobbled by numerous factors including salary-stiffed star Adrien Brody’s lawsuit against the producers.

Still, considerable excitement greeted the news that Argento would at last make a final film in the “Three Mothers” trilogy commenced by Suspiria and Inferno. (These “Mothers” are three witches who secretly control and bedevil the world, a concept the writer-director took from a prose fragment by opium-eating 19th century scribe Thomas De Quincy.) More widely distributed in North America than anything of his in some time, 2007’s Mother of Tears duly featured Nicolodi and their daughter Asia Argento (his frequent lead actor since Trauma) in a berserk tale of witches worldwide descending on modern-day Rome.

Lacking the hypnotic visual surfaces of those preceding installments, this “Third Mother” nonetheless at least partly made up in sheer daft energy whatever it lacked in style or sense. Whether its humor was wholly (even partially) intentional or not, it provided ample evidence that Dario Argento remains a man who very much enjoys his work. There is, even after so many decades’ passage, arguably no notable director of whom one can so confidently say that he loves people precisely to the extent that he can lovingly orchestrate their elaborate death scenes.

And lest you think this really is “just a job,” Argento heartily encourages fans to think he’s a bloodthirsty nut: He’s admitted that when his movies call for shots (as they very frequently do) of an unidentified assailant’s arm stabbing, strangling, etc., a victim, he almost always “plays” the murdering disembodied limb himself. Even Hitchcock’s cameos weren’t so luridly incriminating.