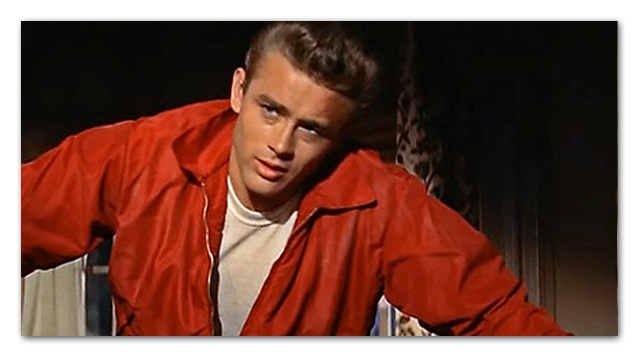

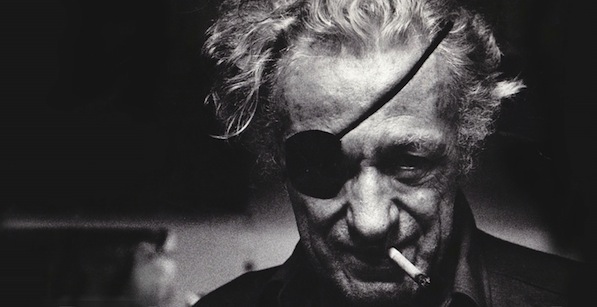

The creator of Rebel Without a Cause, Johnny Guitar and, many films and revolutions later, We Can’t Go Home Again, “is known for his emotional understanding and his capacity to push a scene past its tipping point,” says Nicholas Ray’s widow, Susan Ray. “But what I think is less celebrated is that he really was a completely heart‑felt humanist. He really cared about what happens to human beings. That was what fueled his work. If he couldn’t have made films he would have found another way to express it.” What follows is a conversation between Fandor co-founder Jonathan Marlow and Susan Ray on a variety of projects demonstrating that humanism from the Nicholas Ray Foundation, which is engaged in preserving Ray’s work and honoring his genius.

Susan Ray: Here is Alan Lomax’s quote. I think you’ll see why it means something to me. ‘When I met Nick [Nicholas Ray] in Washington in the 1930s, he was certainly one of the most splendid young men in the whole world. He seemed to me to be a person I’d always dreamt of being. He was very powerful and gentle and wonderful to look at. He had a kind of a grin and a laugh that were the same thing. They were always playing on his face when he was discussing the most serious matters. Where he was far ahead of me was in thinking that you could restart or support all of the many American working‑class cultures with the techniques and the dreaming of sophisticated theater people. He was ripe from the theater of action in New York and full of that dream, as all of us in Washington were. It’s very important to see Nick as a product of the New Deal, and me as a product of the New Deal. The New Deal was the time of the American Revolution begun again. It wasn’t just dealing with the Depression, it was dealing with all the problems that had accumulated through selfishness and greed and exploitation and killing Indians and enslaving the blacks, excluding the poor whites. We were interested in the arts and literature, interested in the discovery of the unknown America through the voiceless people who weren’t at all voiceless; they were vocal as hell if you just stopped to listen to them, who had all the best music and all the best talk and all the funny jokes and all the interesting experience. Nick was interested in the real raw guts at the bottom of the grassroots, where the shit piles up. What he was doing was a very big cultural job. This, by the way, is the definition, for me, of filmmaking as a way of life. He began to do movies like fieldwork. If he’d go to a place, he’d start recording it. He would learn everything about it himself, then he would turn that absolute, total absorption of the area, the contents, the people, the habits, into a film. He didn’t just stop with some romantic cartoons of things that he did; he really went into the depths of the language and of the character structure. As you know, sometimes he risked his life to be with very tough people to see what it was really like there. I think what he set out to do was to show America what it was like. It was a gargantuan ambition. He did that, and he did it at a time when it had become impossible to do it, and he did it. It was a huge trick. I learned from him that it was possible to take what you learn and turn it into a new vision for a whole damn nation. I didn’t know that before; I learned that from him. A very big deal of everything I’ve done is due to him. He didn’t teach me that by giving me any lectures, he just showed me that it could be done.’

Jonathan Marlow: You’re saying that your concept of [the documentary master class] Action! has changed as a result of this quote?

Ray: It hasn’t changed. It’s expanded.

Marlow: It’s evolved.

Ray: It’s still a teaching film. It will still deal with the nuts-and-bolts of the craft. You know Marco Muller, I’m assuming?

Marlow: I know of him but I do not know him personally.

Ray: What he suggested was that we make one full‑length feature and then complete five to seven half‑hour segments dealing with specific aspects of film craft. I think it is a really interesting idea. It is going to be a heck of a lot of work and it’s more than is in my budget but I think it is doable.

Marlow: At this point, does the Nicholas Ray Foundation have prints of his films?

Ray: No.

Marlow: That is what I suspected.

Ray: Nick didn’t have any rights most of his films. The only rights he had were two films with Paramount. Both of them, according to the latest statements I saw, are still showing a loss. Savage Innocence and Bitter Victory.

Marlow: I don’t believe I mentioned this to you earlier but I used to run a small theater in Seattle over a decade ago and one of my favorite screenings was a 16mm anamorphic print of Bitter Victory. It was pristine, I presume because most people didn’t have the correct lens to exhibit it. It looked as if the print had hardly been screened at all. It was one of the most amazing screening experiences I’ve ever had. It is such a stunning film. Beautifully photographed and beautifully constructed.

Ray: That is my favorite film of Nick’s.

Marlow: It is unfortunate that so few people have seen it.

Ray: It is an extraordinary film. I don’t know any film like that film. It is a film pared down to pure image and dialogue. There’s nothing extra in it.

Marlow: You’re right. I guess it is not clear to me at this point how Action! will be constructed. I like the idea of the story-world, in this instance. In some respects, it gives you more freedom in the feature-length piece to touch on things without having to go fully into depth. Then you can use the stand-alone pieces to go into depth on topics that the feature-length documentary wouldn’t allow.

Ray: The advantage of the segments is that they probably will not require shooting. We’ll use Nick’s films, Hollywood films and the Ray Archive. We have about 110,000 feet of film he shot around We Can’t Go Home Again at the Village Vanguard, footage he shot of Willie Nelson in 1974, footage from the conspiracy trial (which is where I met Nick). We have all that to draw on. It had actually been his idea to use the outtakes from We Can’t Go Home Again to illustrate what not to do. Because these were students shooting it. We can use that and we can use the Hollywood films as contrast. At that point, obviously, we would do the feature first. I’ve already lined up researchers. I need one or two more but my plan is to do very thorough research both in terms of photographs, music. I’d like to use some of the music that Nick collected. Films. Related films. And also paintings. Thomas Hart Benton. Do you know his paintings?

Marlow: Absolutely, yes.

Ray: I think they’re extraordinary. Between you and me, what I would like the film to accomplish a couple of things. One is that I’d like it to help people to fall back in love with this country and also the grassroots that Alan talks about. The years before Nick went to Hollywood, he traveled this whole country. I don’t know how much you know about his life. He did collect folk songs with Alan. He worked for the resettlement administration. He was going all over the backroads of this country. He never lost the ability to talk to anyone in their own language, eye-to-eye. He was making ‘community theater’ with miners and with labor union people. He studied with Frank Lloyd Wright. I discovered fifteen letters between them… letters that even Bernard Eisenschitz didn’t know about. I would like to use his exploration of this country since that was essentially his apprenticeship. But I also want to show what he was seeing. They Live by Night, for instance, was taken directly from his experience in Texas with Alan.

Marlow: I think that is apparent. There is an authenticity to the performances in They Live by Night that is unusual in films of that period. There is something particularly honest about what he is capturing in that film. You don’t really see that in other studio films of the era.

Ray: He is known (and rightly, in my opinion) for his emotional understanding and his capacity to push a scene past its tipping point, emotionally. But what I think is less celebrated is that he really was a completely heart‑felt humanist. He really cared about what happens to human beings. That was what fueled his work. If he couldn’t have made films he would have found another way to express it. That’s not just me saying that. He said it!

Marlow: I think that is very evident in his work.

Ray: The idea with this film is to convey not only the nuts and bolts of technique but also that element of caring and of engagement with his world and also to deal with some of his fairly prophetic takes on our culture. What he had to say about technology forty years ago is mind-blowing. The film is going to be largely audio‑driven, taken from 200 to 300 tapes of him talking either with somebody or to himself or just making notes.

Marlow: These materials are already digitized?

Ray: I have almost all the sound digitized. We still need to digitize about two‑thirds of the footage. That’s a sizable chunk of our budget, as you would imagine. That’s in film storage in Los Angeles at present. It would be digitized and then we would send it actually to Austin where Nick’s archive is right now.

Marlow: Right. You have somebody that’s working on that now? Or you’re waiting until you have the money to make that happen?

Ray: I don’t have any money to make it happen yet, no.

Marlow: You’ve mentioned the EYE Institute in Amsterdam on a few earlier occasions. What is the catalyst for those references?

Ray: The EYE was the primary backer of the restoration of We Can’t Go Home Again.

Marlow: I was first able to see it at the Pacific Film Archive a few years ago. It wasn’t until that moment that I discovered that Steve Anker, former Executive Director of the San Francisco Cinematheque, was involved with the film.

Ray: I did an interview with him for Don’t Expect Too Much. We didn’t include it. We may include it in this next one.

Marlow: You were involved in that whole production of You Can’t Go Home Again, right?

Ray: I was. I wasn’t one of the students but I was with him.

Marlow: You were there on the set, of course.

Ray: You can’t be with him unless you’re involved!

Marlow: Yes, exactly.

Ray: I did help write the first treatment of it.