If you were to see a list of the films I have attended during these first few days of the Sundance Film Festival, you would likely think I am morbidly serious. My schedule was filled with nonfiction films on revolution, imprisonment, AIDS, hate, murder, copyright law, natural disaster, though one fictional movie focused much of its narrative on whether Matthew McConaughey wore a shirt. He mostly did.

If you’ve never done this before—in the span of two days watched six or seven movies on topics that reveal the worst (and sometimes, best, but mostly, worst) of global society—I can’t say that I absolutely recommend it. But it is interesting to notice patterns across differing contexts; the films start to feel blended together. It’s a good opportunity to try out an experiment that Miranda July writes about having done in her most recent book It Chooses You called the “Missing Movie Project.”

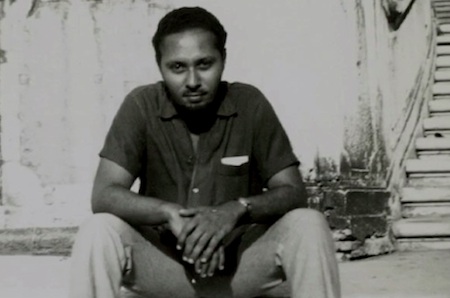

The broad idea of the Missing Movie Project is (was actually; it’s not an ongoing project for July) to define the movie that one thinks is currently needed. What seems like it should be there, but is not? On programming assignment for the San Francisco Film Society, I had been feeling something missing in the works that I was viewing, and at the end of The Stuart Hall Project, I realized what it was. In the film, which constructs a biography of the cultural critic’s life using only archival footage and the songs of Miles Davis (an ambitious structure to take on in a film), Hall paraphrases Antonio Gramsci, “We should hold a pessimism of intellect and optimism of will.” He is talking about the hard problem of inevitability that has creeped into our approach to oppositional politics. What he means is that we must strive to understand our social situation and even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, we should try to find a way to change our situation through action; we should hope that our will can in fact effect change. This quote comes at the close of the documentary, but it’s the vision of how that is done that I think is the missing movie. How is it that the cyclical repetition of crises depicted over and over in the myriad social issue docs that are presented here be interrupted and changed?

The movie that I keep finding missing is the one that pessimistically asks, ‘Is the way that we frame and produce information part of the problem?’

It’s a lot to ask of the films, because, of course, they weren’t made to fulfill my wishes. And, by and large, what I have seen at Sundance is in fact solid journalistic style documentary filmmaking. The films lay out an issue clearly with pertinent research and access to fascinating subjects. But what these films do present often aim in the direction of the basic and anxiety-provoking problem: how does it work and what can we do? Repeatedly, we can see disenfranchisement, corruption and capitalism simmering in another strange brew.

One might ask, isn’t clear access to an issue enough? Something that is evident is how much more quickly smart documentary films can be made than in the past. For instance, Pussy Riot —a Punk Prayer, presents events surrounding the Russian performance artists/activists/band Pussy Riot, including their performances, trial and interviews with the member’s families and lawyers. The flashpoint took place in February, 2012 and the film includes that occasion with background material about it and other events that took place as late as October of last year—and now it’s all there onscreen in a theatrical film. Fallen City, detailing the aftermath of the massive earthquake of the Chinese Sichuan province in 2008, by following three stories, includes an impressive range of detail and information up through 2012 in its story as well. And The Square featured embedded footage of the Tahrir Square occupation in Egypt beginning with the fall of Mubarak’s regime and past Mohamed Morsi’s election in June 2012. At the end of the film, an endtitle announces that the story of the Egyptian revolution continues. As with all of the films presented, one begins to feel that today documentary projects can simply be ongoing, open-ended, constantly re-edited and updated.

The films I saw reveal ways that fissures in the social system are best leveraged by those who have access to economic power. Capitalism is a powerful force in the background in all of the social documentaries I saw, but more specifically the films show how capital power rushes into breaches—just after natural disasters, revolutions or killings—as in the reassertion of law and order in the films mentioned above or in the troubling way that money is used to spread hate as revealed in God Loves Uganda. In God Loves, the relationship between fundamentalist Christian evangelicals and the move for changes in the political policies of Uganda to outlaw homosexuality are investigated and exposed.

One could argue that these two concepts, innovations in the rapidity of media to expose and present injustice on the one hand and the crushing use of economic force on the other are the two sides of capitalism, revealing the neutrality of capitalism as a system. The argument would be that the rapidity of media is democracy in action due to the powerful access we have to information. But I think it should be questioned whether that is the correct assumption. I suspect that innovations in the speed and ubiquity of media and the impoverishment of the disenfranchised are just two expressions of the same system, embedded and synergistic. In the doc Google and the World Brain, contradictions in the commodification of information as both a democratizing and disenfranchising practice, as depicted through the Google Books project to digitize every book in existence is explored. It is ironic, because this is what is happening at the festival too, of course. We are educated and the outrage is being packaged and sold. The movie that I keep finding missing is the one that explores that concept, the one that pessimistically asks, “Is the way that we frame and produce information part of the problem?” It’s the movie that hopefully answers, “This is the way out.”