In a very real sense, the Canadian actress and director Sarah Polley has grown up in public. The daughter of actors, she began her career as a child, achieving prominence in the television series ‘Road to Avonlea’ before she reached her teens. Her sensitive, strong performance was crucial to Atom Egoyan’s masterpiece, The Sweet Hereafter (1997), and led to roles in films by David Cronenberg (eXistenZ), Doug Liman (Go), Michael Winterbottom (The Claim), Hal Hartley (No Such Thing) and Isabel Coixet (My Life Without Me). Her next screen appearance is a pivotal part opposite James Franco in Every Thing Will Be Fine, Wim Wenders’ parable of guilt and forgiveness shooting later this year.

Polley started directing short films in the late nineties and, while still in her twenties, adapted Alice Munro’s short story about an elderly couple grappling with the effects of Alzheimer’s for her beautiful and unexpected feature debut, Away from Her (2006). She followed with another evocative exploration of the nuances of marriage, Take this Waltz (2011), starring Michelle Williams and Seth Rogen.

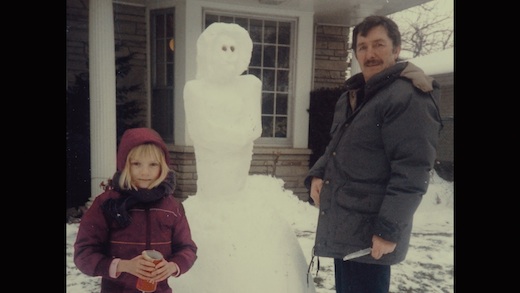

Her fascination with the ups and downs of long-term relationships is decidedly unusual for a young filmmaker, and provides all the evidence one needs to recognize that there are darn few promising directors as mature, serious and playful as Sarah Polley. It derives from her parents’ marriage, we discern from her amusing, thoughtful, wise and poignant first-person documentary, Stories We Tell, and her mother’s death from cancer just days after Sarah turned 11.

As you might glean from its title, Stories We Tell is as much about memory, family myths and the art and practice of documentary in the 21st Century as it is about the curious saga of the Polley clan. The marvelously creative and uncommonly smart film opens May 10, 2013 in New York, and in numerous cities in the coming weeks. We met the gargantuan talent and diminutive person that is Sarah Polley on an unseasonably warm late-April day after Stories We Tell screened in the San Francisco International Film Festival.

Keyframe: Do you draw a distinction between narrative and documentary, or is the line blurred? Or do you just think in terms of ‘movies?’

Sarah Polley: I think I draw a distinction generally. I would certainly generally choose to see a documentary before I would see a narrative fictional film. I think I’m generally just a bigger fan of the medium of documentary. I think I was a lot more frightened to make a documentary than I would have been to make a narrative fictional film because I love documentary so much, it’s a lot more intimidating for me.

Keyframe: Because you hold documentary to a higher social purpose?

Polley: I just enjoy them more. The truth is I could watch a terrible documentary and still be entertained for two hours, whereas if a film is fictional and bad I feel like I want to pull my fingernails out. (Laughs.)

Keyframe: Why do you think you can watch a bad documentary?

Polley: There are still real people in it, and I find real people a lot more fascinating than actors.

Keyframe: But I doubt somehow that you can watch reality TV.

Polley: I don’t, because it feels exploitative generally and manipulative, and not actually like we’re just watching people in their lives. It feels much more of a construct.

Keyframe: You know the critic David Thomson?

Polley: Very well, yeah.

Keyframe: We were talking last year when his latest book, The Big Screen, was published, and I brought up documentary and he said, ‘I just think of documentary as another genre of film, one in which they cast nonprofessionals.’ Just another form of entertainment.

Polley: Yeah. I don’t necessarily dispute that. I just like it more than the other kinds of [filmmaking].

Keyframe: Let’s talk about Stories We Tell. If you get on a bus in San Francisco, some stranger might well start telling you all about himself. In Canada, however, I don’t think it’s quite that way. Perhaps you could translate for us how much more gutsy and risky it is to expose yourself, and your family saga, onscreen in your country.

Polley: I never thought of that, actually. I think it would be hard for me to translate because it’s not something that occurred to me, but I suppose you’re right. I’ve never thought of it but it’s an interesting point of view.

Keyframe: Maybe it says more about my stereotype of Canadians. Let me throw something else out. Is it easier or harder to reveal yourself in Stories We Tell than in films in which you’re acting? It may sound counterintuitive, but isn’t an important part of acting putting yourself into the character, and not hiding behind the character?

Polley: I think definitely in Stories We Tell it was more challenging and much more terrifying to reveal myself, because I didn’t have a character to hide behind. Not just exposing myself but exposing my parents and my siblings is a very, very scary and dangerous enterprise.

Keyframe: How do you view your responsibility to the subjects of a doc?

Polley: I view it as huge, which is probably why I’ve never made one before and why it might be hard for me to figure out how to make one again. I feel like when you expose people to a public who’s never going to meet them, and you’re creating a representation of them that will be the only image that some people will have of that person, I think that you have to take a lot of responsibility for that. You have to take it very, very seriously, and I’ve certainly seen documentaries that don’t do that. I think it was easier for me to have a built-in barometer of whether what I was doing was ethically OK or not OK because I had relationships with everybody involved. So I think it was easier for me to gauge what was manipulative or truthful or when I was making decisions with or without integrity than if I was dealing with strangers and I was too engaged in just the film and not the people.

Keyframe: Everyone has their own view of how they present themselves to the world, but your brothers and sister come off fabulously. I’d love to have a cup of coffee with any of them and talk about whatever. But who knows? Maybe you cut out all the mean bits.

Polley: Exactly. What I really wanted was to create an accurate sense of who everybody was as far as I knew, without trying to manipulate it too much one way or the other. I really wanted people to be who they were, as much as I could. That isn’t to say there’s every aspect of everybody in the film. My siblings and my dad and Harry [Gulkin] all have many aspects of their personalities that are not in the film just because there wasn’t the time to do an in-depth character study of everybody. But as much as I could I tried to be accurate to what my sense of them was.

Keyframe: What we’re talking about now is the editing process. Was that the most painstaking part of making the film?

Polley: The editing was pretty painstaking, and also there was a month and a half where all we did was watch footage. We had hundreds of hours of footage, so we literally had a month and a half just watching what we had already done, which was pretty exhausting. And then assembling it, it was very, very hard to see the film or the artistry in that; you’re just cobbling together a basic structure and a basic story. So I think we edited altogether for about eight or nine months, spread over a few years.

Keyframe: At some point does it not seem like your family? Do they just become characters in a film?

Polley: Kind of, although I’m never going to be distant enough from it that I can see what other people see. That’s the frustration of this film, I think, for me, is that with the two films I’ve made that aren’t documentaries and where there are people I know in them, I feel like I can kind of see what an audience sees. Or if I read a review, whether it’s good or bad, I can kind of see that perspective, and there’s something satisfying about that. With this film, I literally cannot see this film through anyone else’s eyes but my own. I am too close to it. Even when people really like the film and they say why, I find it frustrating because I can’t actually see what they’re seeing. I would just love to be able to watch this film through a stranger’s eyes just once. Just so I could see what people actually look like, and what the story even is. To me, it’s still kind of a mess. I mean, it’s a very carefully crafted mess that I worked on for many, many years, but I just look at it and I’m completely perplexed about what the hell it is. So it’s great that people had a positive response but to be honest with you I have no fucking clue what it is. (Laughs.) I’m as confused as I was when I started it. I probably shouldn’t say that, but. (More laughs.)

Keyframe: Whenever I watch a first-person doc, not to pigeonhole Stories We Tell in a category, the first test for me is, Does this transcend a home movie?

Polley: Yeah, yeah.

Keyframe: Is it universal? Which seems like an easy hurdle, maybe, and you clear it by a mile. But I wonder if you had any concerns along the way, existential and otherwise.

Polley: One of the things I did in the year that I was sort of in development with this film before I started shooting anything was watch every personal documentary I could get my hands on. And the process made me absolutely terrified and generally squeamish, often nauseous. There are a few great personal documentaries, but there are so many that could and should be great that are just so kind of self-involved and narcissistic and, really, a kind of therapy that I don’t necessarily want to be in the room for. You know, even some of the good ones feel like that sometimes. And I was so horrified at putting myself in this position and, for me, that would have been the biggest pitfall, because the impetus for making this film was not the story of my life at all; it was what came out of it. It was all of the stories being told about this event and how they drifted away from each other, how they came together, and this kind of cacophony of voices around one set of events was what I was interested in. But to do that, I had to tell the story from my own life. It was so easy to be tempted to make the easier film, which was just about that story. And certainly there were pressures along the way to just make it a very simple story, and to not make it too complex and to not be pretentious about it—and certainly that was a concern, as well—but for me, pretentiousness was the least of my concerns compared to having some kind of voice-of-God voice-over about my feelings about things. (Laughs.) I would much rather have been accused of being obnoxious and making things too complicated.

Keyframe: Well, there’s pretentious and there’s self-awareness that everyone knows there’s a movie going on, and everybody knows there’s a camera in the room when you’re interviewing people.

Polley: Yeah, exactly. I think at this point it’s profoundly disrespectful, actually, to an audience to pretend there isn’t a camera there when you’re making a documentary. ‘We are not idiots anymore.’ I think moviegoers are incredibly sophisticated even if it’s not what they do for a living. People get it, people get the medium, people get when they’re being manipulated. And I feel if you’re going to make a film that isn’t just about the story, that it’s about storytelling itself, you would be pretty naïve to think you could get away with leaving the construction of this story out of it. And the manipulations. Because this isn’t hard fact. This isn’t really what happened. This isn’t even an accurate depiction, probably, of everybody’s version. I am ultimately making decisions in an editing room. I am manipulating the process even when I try not to. So that became a necessary part of telling this story.

Keyframe: Can you mention some of the first-person docs that you took inspiration from?

Polley: Absolutely. I loved Doug Block’s film, 51 Birch Street. I thought it was really interesting. Probably the biggest influences on me for this film would be Lars von Trier’s film [with Jørgen Leth], The Five Obstructions, which I just think is such an amazingly bold, risky, terrifying experiment where he really puts himself on the line and does something so beautiful. I loved F for Fake by Orson Welles, which is not a personal documentary but turns into something other than what it seems to be.